Paying Homage: Liz Lerman’s Choreography in Wartime

“Appalachian Spring” with the University of Maryland Symphony Orchestra, Gildenhorn Concert Hall, Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, College Park, Md., May 4, 2014

“Healing Wars,” world premiere at Arena Stage’s Mead Center for American Theatre, Arlene and Robert Kogod Cradle, Washington, D.C., June 6-29, 2014

By Lisa Traiger

For decades now, initially as founder and artistic director of Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, now as an independent itinerant artist, choreographer and public intellectual, Liz Lerman has been pushing dance outside of its traditional boundaries. She has choreographed in train stations, at a naval shipyard, in art galleries, and in the red-carpeted grand foyer, the women’s rest room and the loading dock at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.

Her dancers have long upturned expectations — ranging in age from their early 20s to well into their 70s and beyond. Some have been trained in dance techniques from ballet to Graham, Cunningham, and release; others are neophytes, maybe young children or residents of a retirement home who haven’t had a minute of dance performing experience. No matter, Lerman is a master of choreographing for a diversity of bodies, experiences, ages and expertise. She has a knack for making everyone look their best by allowing for gradations and careful pruning of movement material, often down to the simplest of gestures that speak volumes.

This past spring, two new Lerman works brought her back to her long-time home turf in Washington, D.C., and the Maryland suburbs, three years after she walked away from the company she bore and built beginning in 1976. The Dance Exchange remains active at its Takoma Park, Maryland, home on a more localized level than under Lerman’s guidance. On her own, Lerman has found more time to experiment and to delve deeply into projects that matter for her right now.

Her second collaboration with an orchestra, the University of Maryland Symphony Orchestra, proved a fruitful follow-up to the lovely, spare and unapologetically rigorous rendering in 2012 of Claude Debussy’s prelude for Afternoon of a Faun. There Lerman, along with the collaboration of conductor James Ross, pulled the chairs out from under the players and crafted movement sequences, groupings and even a few balletic steps that the instrumentalists could master while simultaneously playing the score to fine effect. Initial comments prior to experiencing this newly realized setting of an orchestral score, amounted to snide questions about violinists and cellists being equated to marching band musicians (who, by the way, are no slouches in either musical proficiency or embodied movement).

“Appalachian Spring” with choreography by Liz Lerman for the University of Maryland Symphony Orchestra

This past May 2014, Lerman and Ross tackled a 20th-century American classic: Aaron Copland’s vibrant score for Appalachian Spring. Of course, much historic resonance accompanies the work. Copland’s commissioned work, scored for a chamber-sized orchestra, premiered at the Library of Congress in 1944 with Graham’s choreography. This piece of Americana, which blends national values of independence, manifest destiny and the communal spirit, could not have been more prescient coming out as the United States was entangled in World War II, with its native sons stationed across three continents from Europe to the Far East.

Copland titled his 30-plus minute dance score Ballet for Martha, while Graham took inspiration from Hart Crane’s poem “The Dance.” Lerman’s take on the work includes homage to the Graham original, an acknowledgement of its inherent American melodies and rhythms and, most distinctively, a deeply contemplative regard for the mystery and reward of artistic inspiration. It’s as if the ballet has riffed on itself and on the juicy and productive thought processes of its original creators – composer and choreographer Copland and Graham – in seeking a higher level of inspiration and communion.

In Lerman’s piece, Copland’s work opens with soft arpeggios and the musicians, freed from their chairs, enter; first a chamber-sized group walks and plays the clarinet, oboe and other instruments contributing to Copland’s thematic material. Clad in denim and khaki, shades of blue and beige, some players barefoot, others in sneakers or boots, they walk, sway, skip, dash and fall into formations.

A quartet of string players lifts their bows into the center of a circle as they suggest a living carousel. The cellists have their instruments strapped to their shoulders so they can still maneuver the steps of the Gildenhorn Concert Hall stage. A bass player hoists his instrument high above his head a few times during the piece. There are nods to Copland’s Americana themes: do-si-dos and allemands without the hands, lines and circles weaving in and out like a reinterpreted square dance as the instrumentalists play and maneuver.

The work’s centerpiece though, both visually and morally, is long-time Lerman associate Martha Wittman, who possesses more than a half-century of dancing, teaching and performing experience. She sits initially at a small desk, channeling the creative artist in her element as she simultaneously pays an homage to both Copland and Graham, the two highly opinionated creative forces behind this quintessential American work. And Wittman with Enrico Lopez-Yanez, a graduate student in conducting, serve as the work’s drum majors or pied pipers, leading lines and circles, spirals and whirling vortexes of string players and woodwinds, brass and drums around the stage, which has been carefully and lovingly lit in evolving shades of cool blue and warm yellow to compliment the mood and tenor of the musical passages.

Lerman also pays a sense of tribute to the staunch and angular canvas that Graham crafted in telling her tale of a frontier marriage and the complex psychological forces that spurred her inner turmoil. In Lerman’s hands, though, the movement loses this mid-century modernist gloss for something far more lyrical, democratic and (Lerman’s calling card for decades now) easy to read and render, by dancers and non-dancers alike.

Lerman, with creative co-choreographic input from Vincent Thomas, another former dancer in her now-defunct company, has drawn upon multiple talents of these mostly graduate school-level musicians. Not only can they play, but some (a violinist at one point) can play bars while dancing a jig, a flutist can skip upstairs and not miss a beat, and a trio of men can lift up a bassoonist on another student’s back in a circus-y moment that underlines the sense of play that Lerman has drawn from these otherwise serious musicians.

Thomas (who has a perfect background as a choreographer for college flag teams) and Lerman have been able to draw out a surprisingly rich, varied and daring palette of movements from these budding orchestra professionals. The risks they have taken to play and maneuver do not seem to have taken much toll musically on the Copland score. And if there were glitches from time to time, they were more than made up for by the liveliness and intensity of commitment these musicians had for the project.

Once the piece arrives at the “Simple Gifts” theme, with its moderatos and crescendos, it’s hard not to be sold on this project. Then in a final act of spiritual offering, as the theme wanes and returns to its sparest melodic lines, the musicians step to the edge of the stage and place their instruments – flutes and French horns, clarinets and basses, violins and oboes – lovingly on the floor before stepping back and leaving the final notes to the clarinet and xylophone and final movement to Lopez-Yanez and to Wittman. Wittman recapitulates a simple hand gesture: her open palm held aloft, balancing and tossing the unseen.

Wittman has held the orchestra and audience in her thrall. Within that softly executed moment is a world of creativity. It’s the magical life force of how music and dance, poetry and song, come into being. Lerman’s Appalachian Spring gifts us with the drama of the creative force itself in all its glory, mystery and spirituality.

Among Lerman’s ongoing creative projects is her continuing experimentation in what she has called “non-fiction dance” or “non-fiction choreography.” Many of her works spanning her more than four decades of dancemaking have drawn deeply from her personal experiences, along with those of her dancers (whether professionally trained or not) – her chief collaborators. In complex, multifaceted evening-length works she has addressed the mapping of the human genome (Ferocious Beauty: Genome), the origins of everything (The Matter of Origins), the harrowing Nuremberg trials (Small Dances About Big Ideas) and the massive reach of Russian history (Russia: Footnotes to History), to name a few of her large-scale, intensively researched pieces. Lerman’s latest work deals – emotionally, viscerally, practically and historically – with war and its aftermath on individuals.

Healing Wars, which made its world premiere in June 2014 at Arena Stage’s Mead Center for American Theatre in Washington, D.C., alternates both effectively and ineffectively between two American conflicts: the Civil War and the present-day wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Under Lerman’s directorial influence, these events, separated by history and 150 years, are both equated and contrasted so that in an 80-minute evening, the build-up of concepts and ideas becomes overwhelming.

At times it’s easier to shut down than take in one more sound-bite, revelatory confession or factoid about war, medical advancements, healing and return home. One way Lerman accomplishes this is by examining and exploring the smallest of details – the incremental overrides the universal. One doctor’s story of a surgical incident, one soldier’s experience with the ramifications of an exploded IED, one woman’s tactics to survive on the home front, knowing her partner is far from home with danger close by, are told and meant to be instructive and didactic in result.

Lerman’s biggest pieces work through accretion – the additive nature of these vignettes; narratives performed in words and gestures; images, ideas, confessional passages; choreographic tidbits; and other viscera she accumulates. They often finally overwhelm, yet simultaneously they unfurl, with effective and salutary results. Dance, movement, narrative, individual experiences are universalized and by documenting them they become something greater than the one. In Lerman’s hands they become representative of the man, and universalize (in this case) our (and others’) experiences of war and its aftermaths.

She does this with the able choreographic assistance of one of her long-time affiliates, dancer Keith Thompson, as well as co-artistic collaborators Heidi Eckwall creating lighting; Darron L. West, contributing sound; Kate Freer providing the multimedia and video elements; and David Israel Reynoso crafting the unobtrusive sets (including the most compelling, a chandelier-like mobile of hanging military cots) and the simple but effective costumes that draw on Civil War and modern military garb.

As much devised theater as it is dance, the performance begins before the audience even enters Arena’s most-intimate space, the Cradle. Led in the back way via the stage door in groups of about 12 to 15, one walks through a museum-like collection of life-sized, living dioramas, each populated with a performer recreating a moment from the Civil War era or from today.

There’s Alli Ross, perched on a high stool-like bicycle seat, a woman disguised as a Confederate soldier. She is glimpsed through a broken window, a closed room with an off-kilter bed hung from the ceiling (foreshadowing Reynoso’s set). And Tamara Hurwitz Pullman, properly clad in a hoop skirt, portrays Clara Barton, founder of the American Red Cross, as she sifts through thousands and thousands – 63,000 according to a museum-like placard nearby – of letters requesting information about missing Civil War soldiers.

Ultimately, the final vignette both dramatically and morally becomes, the centerpiece in the 70-minute work. Hollywood actor Bill Pullman (Independence Day) shares a bench with Paul Hurley, a former U.S. Navy gunner’s mate and graduate of Duke Ellington School for the Arts in Washington, D.C. They chat casually about Hurley’s wartime experiences. I overheard his telling of an epic bar fight between Australian, German, Dutch and Greek soldiers. The Aussies started it, he claimed. Unspoken, at least in the snippet I heard, but later revealed, is the narrative detailing how Hurley lost his leg in Bahrain and how he faced an arduous recovery.

As the audience files into their seats, Samantha Spies meanders the stage, lantern in hand, her rough-cut burlap dress indicating her slave caste – but her presence more otherworldly spirit and angel than downtrodden slave. Her guise provides an elemental and earth-centered connective thread to root African movement traditions, while suggesting to an ephemeral spirit’s presence. Spies helps the viewer switch between present and past, between realistic and otherworldly realms, between the Civil War and Afghanistan and Iraq, between modern-day operating room and deathbed. It’s hard to misconstrue her true role once she completes her monologue – she’s an angel leading characters to their deaths, gently or gruesomely.

Actor, and here monologist extraordinaire, Pullman serves as the work’s core: he’s both guide and example, playing a military surgeon who lectures before a group of patrons back on the home front. In Hollywood films Pullman has played an American president, so his authoritative demeanor almost steamrolls some quieter, less specific moments. But the evening’s centerpiece arrives when Pullman and wounded vet Hurley converse. Hurley removes his prosthesis and performs a duet giving himself over to dancer Thompson, who has crossed over from Civil War to today as a supportive partner in the wounded man’s healing. The compelling moment – undeniably, ultimately self-sacrificing and draining — demands that attention be paid.

Our wars – American wars – are fought in distant lands. Lerman’s goal with this project was to bring the present-day wars and their aftermath home, just as, in its time, our nation’s largest and most divisive war, the Civil War, touched nearly every household and life as citizens witnessed battles and the tragedy of the wounded and dead in their midst.

Lerman’s work in drawing together these disparate but not dissimilar moments of history, along with the science, medical advances, politics and, of course, personal experiences, forces contemporary audiences to pause and consider that as individually painful as war traumas are, the suffering that results is our nation’s burden to bear. Lerman, here, through the compelling forces of dance theater, underscores the gravity of that burden.

© 2015 Lisa Traiger

This review originally was published in the Spring 2015 print edition of Ballet Review (p. 20-23). To subscribe, visit Ballet Review.

A Year in Dance: 2014

By Lisa Traiger

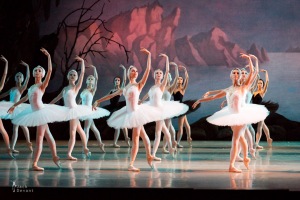

My year 2014 in dance opened in January with the return of the now annually visiting Mariinsky Ballet to the Kennedy Center Opera House. Though the company brought Swan Lake, the company’s signature work – created on this most famous classical troupe by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov in 1895 – was not what we saw. Instead the “Sovietized” Konstantin Sergeyev 1950 version, filled with pomp and additions startling for Western audiences (a second corps of black swans, for example, in the “white” act), was on offer. Ultimately, the true star was the singular corps de ballet. Who can resist the Mariinsky’s 32 perfectly synchronized white swans in act two? The impeccable Vaganova training remains one of the Mariinsky’s most essential hallmarks. Even standing still, the corps breathes together as one body; in stillness they’re dancing. The result is simply stunning and awe-inspiring, ballet at its best.

My year 2014 in dance opened in January with the return of the now annually visiting Mariinsky Ballet to the Kennedy Center Opera House. Though the company brought Swan Lake, the company’s signature work – created on this most famous classical troupe by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov in 1895 – was not what we saw. Instead the “Sovietized” Konstantin Sergeyev 1950 version, filled with pomp and additions startling for Western audiences (a second corps of black swans, for example, in the “white” act), was on offer. Ultimately, the true star was the singular corps de ballet. Who can resist the Mariinsky’s 32 perfectly synchronized white swans in act two? The impeccable Vaganova training remains one of the Mariinsky’s most essential hallmarks. Even standing still, the corps breathes together as one body; in stillness they’re dancing. The result is simply stunning and awe-inspiring, ballet at its best.

Compagnie Kafig’s hip hop with a French accent and a circus flair rocked the Kennedy Center in February. Founded in 1996 by Mourad Merzouki in a suburb of Lyon, Kafig’s all-male troupe of athletic dancers flip and tumble, punching out percussive beats and floor work that toggle between their North African roots and b-boy street moves. Merzouki’s latest interest is capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian dance-cum-martial-art. His “Agwa” featured about 100 cups of water, arrayed in grids, poured and re-poured, along with plenty of circusy tricks and surprises. Hip hop dance has for a generation-plus moved beyond its inner-city, thug-life street demeanor; we see the results daily in popular culture, on television and in suburban dance studios. Kafig’s creative and expansive approach drawing from North African and Afro Brazilian rhythms and French circus opens up a whole new world for this home-grown vernacular form.

Compagnie Kafig’s hip hop with a French accent and a circus flair rocked the Kennedy Center in February. Founded in 1996 by Mourad Merzouki in a suburb of Lyon, Kafig’s all-male troupe of athletic dancers flip and tumble, punching out percussive beats and floor work that toggle between their North African roots and b-boy street moves. Merzouki’s latest interest is capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian dance-cum-martial-art. His “Agwa” featured about 100 cups of water, arrayed in grids, poured and re-poured, along with plenty of circusy tricks and surprises. Hip hop dance has for a generation-plus moved beyond its inner-city, thug-life street demeanor; we see the results daily in popular culture, on television and in suburban dance studios. Kafig’s creative and expansive approach drawing from North African and Afro Brazilian rhythms and French circus opens up a whole new world for this home-grown vernacular form.

In April, Rockville’s forward-thinking American Dance Institute presented the legendary post modernist Yvonne Rainer. Now 79 and still making new work, Rainer is credited in the 1960s with coining the term post-modern for dance and as part of the experimental Judson Church movement taking dance into new, uncharted realms. She famously penned her “No” manifesto – “No to spectacle. No to virtuosity. No to transformations and magic and make-believe. No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image” – which has become a de rigueur short reading for any young modern dancer looking to develop a choreographic voice. In it Rainer encouraged a re-thinking of dance without virtuosity, technique, story and beauty. Dance could be the “found movement” we see on the streets every day. For her evening at ADI’s blackbox theater, Rainer didn’t dance, but her five dancers, whom she lovingly dubbed her Raindears, did. “Assisted Living: Good Sports 2” and “Assisted Living: Do You Have Any Money?” were recent, from 2011 and 2013 respectively. They were still steeped in Judsonian traits – lots of game-like patterns and structures as the Raindears jogged the stage like a ragged army of enlisted 5th graders on recess; a montage of unusual music and spoken sections, drawing from classics, opera, popular mid-20th century songs, readings and quotes on economics and more. A dancer drags a mattress, dancers hoist and carry other dancers like movers, Rainer reads and observes from a comfortable perch on an easy chair. First timers to this type of highly conceptual work might leave scratching their heads. But there’s a method to the madness and the accumulation of moments and movement quotes from ballet, tap and vaudeville at various points. Here we have the post-modern notion where everything counts: everything and the kitchen sink get thrown together to make a work. But there’s craft and method behind this madness, this everyone-in approach. Rainer, for me, built a structure that resonated deeply on an emotional level. This pair of works made me think of wrapping up a lifetime, and, more personally, of easing my own parents into their final years: packing up, putting away, remembering and forgetting, burying. This was post-modernism with a new level of poignancy. Though not narrative, it spoke to me in far-reaching ways. When I chatted with Rainer after, I told her how moved I was and how it made me think of my parents in their final years. She acknowledged that while in the studio creating, she was dealing with similar end-of-life issues with a dying brother. Even Rainer, the purest of post-modernists, has come to a place of remembrance and meaning in ways that were unforgettable.

One of the year’s most anticipated events was the re-opening of the region’s most prolific dance presenter, Dance Place, which has long been a mainstay of the now revitalizing Brookland neighborhood of northeast Washington. In June the site specific piece “INSERT [ ] HERE” inaugurated the newly renovated studio/theater. Sharon Mansur, a University of Maryland College Park dance professor, and collaborator Nick Bryson, an Ireland-based independent artist and improviser, fashioned a site-specific piece that took small groups through the space – introducing both the public areas like the studio/theater and spacious new lobby to never seen recesses like the dank underground basement, the artists’ new dressing rooms, rehearsal rooms and a long narrow corridor of open desks where most of the staff put in their hours. Audience members were allowed to meander and pause, take note of a moment beneath the bleachers where Baltimore choreographer Naoko Maeshiba was part girl-child zombie, part Japanese butoh post-apocalyptic figure. Upstairs in a rehearsal room, Mansur and Bryson parsed out parallel neatly improvised solos that reflected and spoke through movement to each other. In a dressing area former D.C. improviser/choreographer Dan Burkholder fashioned his movement phrases with silky directness amid a room of candles and found natural objects. The main stage filled with a wash of dancers sweeping in with celebratory bravado: An auspicious, memorable, and entirely perfect way to christen the space.

One of the year’s most anticipated events was the re-opening of the region’s most prolific dance presenter, Dance Place, which has long been a mainstay of the now revitalizing Brookland neighborhood of northeast Washington. In June the site specific piece “INSERT [ ] HERE” inaugurated the newly renovated studio/theater. Sharon Mansur, a University of Maryland College Park dance professor, and collaborator Nick Bryson, an Ireland-based independent artist and improviser, fashioned a site-specific piece that took small groups through the space – introducing both the public areas like the studio/theater and spacious new lobby to never seen recesses like the dank underground basement, the artists’ new dressing rooms, rehearsal rooms and a long narrow corridor of open desks where most of the staff put in their hours. Audience members were allowed to meander and pause, take note of a moment beneath the bleachers where Baltimore choreographer Naoko Maeshiba was part girl-child zombie, part Japanese butoh post-apocalyptic figure. Upstairs in a rehearsal room, Mansur and Bryson parsed out parallel neatly improvised solos that reflected and spoke through movement to each other. In a dressing area former D.C. improviser/choreographer Dan Burkholder fashioned his movement phrases with silky directness amid a room of candles and found natural objects. The main stage filled with a wash of dancers sweeping in with celebratory bravado: An auspicious, memorable, and entirely perfect way to christen the space.

Long-time D.C. stalwart Liz Lerman, who decamped from her own Takoma Park-based company the Dance Exchange in 2011, returned to the area with another broadly encompassing work, Healing Wars, which had its world premiere at Arena Stage’s intimate Cradle in May. The audience was welcomed in through the stage door, where a “living museum” of characters – Clara Barton penning letters, a Civil War soldier splayed on a kitty corner hospital cot, a woman pouring water libation as a spirit of a runaway slave, and the very real veteran of the recent war in Afghanistan, Paul Hurley, a former U.S. Navy gunner’s mate and graduate of Duke Ellington School for the Arts in Washington, D.C., conversing with Hollywood actor Bill Pullman. Healing Wars examines war, injury, death, and recovery from multiple perspective spanning two centuries: the Civil War era and the 21st century. This was entirely and exactly Lerman’s wheelhouse. The piece was didactic, thought provoking, head scratching all at once. And it does what movement theater should: inspire and challenge. Lerman was determined with this project to bring the present day wars and their aftermaths home for America’s largest and most divisive war, the Civil War, touched nearly every household. By drawing together these disparate but not dissimilar historical moments, along with the science, medical advances, politics and, of course, personal experiences, Lerman has contemporary audiences reflect that as individually painful as war traumas are, the suffering that results is our nation’s burden to bear. Lerman, here, through her compelling dance theater underscored the gravity of that burden.

In September, Deviated Theatre returned to Dance Place with a steampunk quest story envisioned by choreographer Kimmie Dobbs Chan and director Enoch Chan. For the evening-length Creature, the costumes — wings, netting and accoutrements draped and shaped by Andy Christ with second act headpieces full of wire-y netting and fanciful shapes by Dobbs Chan — are astonishing. The dancing here was among the best technically of the locally based dance troupes this year. The primarily female cast stretches like Gumbies, soars from an aerial hoop, maneuvers on two legs or four limbs, crab walking, crawling, scooting, loping in bug-like, inhuman ways. Though the apocalyptic fairy tale meanders, the oddball weirdness – eerie, esoteric, eclectic – that Chan and Chan invent continues to endear.

October brought a troupe from Israel, where contemporary dance continues to be a hotbed of creativity. Vertigo Dance from Jerusalem brought choreographer Noa Wertheim’s Reshimo, with its company of nine unfettered dancers who take viewers on an emotional journey. “Reshimo,” a term from Kabbalah – Jewish mysticism – suggests the impression light makes, the afterimage. The 55-minute work presented an ever-evolving landscape of singular movement statements, accompanied by Ran Bagno’s rich and varied musical score, which modulates between violin, cello, synthesizers and kitschy retro-pop selections. Sexy trysts, playful romps, casual walks and a moment of frisson, explosive and shattering, fully animate the choreographic voice filling the work with resonant ideas.

October brought a troupe from Israel, where contemporary dance continues to be a hotbed of creativity. Vertigo Dance from Jerusalem brought choreographer Noa Wertheim’s Reshimo, with its company of nine unfettered dancers who take viewers on an emotional journey. “Reshimo,” a term from Kabbalah – Jewish mysticism – suggests the impression light makes, the afterimage. The 55-minute work presented an ever-evolving landscape of singular movement statements, accompanied by Ran Bagno’s rich and varied musical score, which modulates between violin, cello, synthesizers and kitschy retro-pop selections. Sexy trysts, playful romps, casual walks and a moment of frisson, explosive and shattering, fully animate the choreographic voice filling the work with resonant ideas.

My year in dance ended on a high note, another company from Israel: the country’s most intriguing, Batsheva Dance Company based in Tel Aviv, returned to the Kennedy Center’s Opera House in November with the area premiere of Sadeh21. The work, by the company’s prolific and long-time choreographic master Ohad Naharin, shows off the dancers’ distinctive abilities to inhabit and embody movement in all its capacities. “Sadeh,” Naharin told me, means field, as in field of study, and the work unspools in vignettes or scenes – some solos, some duets or small groups, some full the company – which are labeled by number on the half-high back wall, the set designed by Avi Yona Bueno. Moments funny and disturbing, sexy and silly include movement riffs that combine the refined and the repulsive, an extended sequence of screaming, another where the men in unison ape and stomp like fools in flouncy skirts. Naharin’s music, like his rangy movement, is erratic, shifting from classical to pop, severe to silly to sweet in game-like fashion. The set design, that imposing back wall, is freighted with multiple meanings. A wall in Israeli context recalls both the ancient Western Wall — the supporting wall of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. But in contemporary terms the wall suggests the one built by the Israeli government to separate Israel proper from the West Bank. Both a protection and a burden, it’s a constant reminder that peace remains an achingly elusive ideal. For Naharin, the on-stage wall literally became a jumping off point. Dancers scrambled up, stood atop the ledge and dove into the inky blackness. That ending is simply gorgeous. Again and again, dive after dive, were they leaping to their freedom, to their deaths, or were they doves, soaring skyward? Continuously, as the music faded and the lights rose, credits rolled like a movie on the wall, as dancers climbed and dove. A taste of infinity. From earth to heaven and back again. I could have watched those final moments forever, they felt so raw, yet whole, risky but real. Final but indefinite. Life as art. Art as life. Batsheva ended my year in dance on a soar.

My year in dance ended on a high note, another company from Israel: the country’s most intriguing, Batsheva Dance Company based in Tel Aviv, returned to the Kennedy Center’s Opera House in November with the area premiere of Sadeh21. The work, by the company’s prolific and long-time choreographic master Ohad Naharin, shows off the dancers’ distinctive abilities to inhabit and embody movement in all its capacities. “Sadeh,” Naharin told me, means field, as in field of study, and the work unspools in vignettes or scenes – some solos, some duets or small groups, some full the company – which are labeled by number on the half-high back wall, the set designed by Avi Yona Bueno. Moments funny and disturbing, sexy and silly include movement riffs that combine the refined and the repulsive, an extended sequence of screaming, another where the men in unison ape and stomp like fools in flouncy skirts. Naharin’s music, like his rangy movement, is erratic, shifting from classical to pop, severe to silly to sweet in game-like fashion. The set design, that imposing back wall, is freighted with multiple meanings. A wall in Israeli context recalls both the ancient Western Wall — the supporting wall of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. But in contemporary terms the wall suggests the one built by the Israeli government to separate Israel proper from the West Bank. Both a protection and a burden, it’s a constant reminder that peace remains an achingly elusive ideal. For Naharin, the on-stage wall literally became a jumping off point. Dancers scrambled up, stood atop the ledge and dove into the inky blackness. That ending is simply gorgeous. Again and again, dive after dive, were they leaping to their freedom, to their deaths, or were they doves, soaring skyward? Continuously, as the music faded and the lights rose, credits rolled like a movie on the wall, as dancers climbed and dove. A taste of infinity. From earth to heaven and back again. I could have watched those final moments forever, they felt so raw, yet whole, risky but real. Final but indefinite. Life as art. Art as life. Batsheva ended my year in dance on a soar.

Lisa Traiger writes frequently on dance, theater and the arts. You may read her work in the Washington Jewish Week, Dance magazine and other publications.

(c) 2015 Lisa Traiger

Measures of Masculinity

Multiple Personalities: an evening of dance by Christopher K. Morgan

Music Center at Strathmore

Bethesda, Md.

May 23, 2010

By Lisa Traiger

© 2010 by Lisa Traiger

Dancer/choreographer Christopher Morgan is a shape shifter. “Multiple Personalities,” his recent concert of choreographic works crisscrosses genres as easily as a smooth, flat stone skipped across a glassy pond. A modern dancer, he effortlessly tackled a balletic pas de deux, a hip hop number and a traditional hula. Although that extreme variety sounds suspiciously like a Dolly Dinkle recital, Morgan displays choreographic intellect in each of the genres he assays, resulting in mostly full-bodied artistic works that interplay narrative, movement ideas and a not insignificant trace of humanity.Currently rehearsal director at CityDance Ensemble, one of the Washington, D.C. region’s fastest growing and most successful contemporary companies, Morgan’s evening of works fits neatly into the intimate CityDance Center studio/theater at the Music Center at Strathmore. Opening with a traditional hula song and chant, expanded with a personal story -– a nod to Morgan’s time spent working with Marylander Liz Lerman’s text-based choreographic endeavors -– the evening also featured a contemporary ballet mostly danced on pointe; a freewheeling modern number with allusions to clubbing and high fashion; and, the program’s strongest and most personal piece, “The Measure of a Man,” a testament of the artist coming to terms with his masculine identity.

In 1987, San Francisco-based choreographer Joe Goode managed to rattle staid sensibilities in the dance world and beyond with the premiere of his gay-identity piece, “29 Effeminate Gestures.” Goode intended to tear down stereotypes with his uber-masculine persona fraught with a series of feminine, read “gay,” gestures. In his butch demeanor he even used a chainsaw to chop up a chair on stage, then mumbled, over and over, “He’s a good guy. He’s a good guy,” as if saying it would make it so. Goode tried to convince himself that he could somehow possess the masculine mystique: that John Wayne tough and independent streak and the notion that real men, of course, shed no tears. The work “29 Effeminate Gestures” examined what happens when one suppresses one’s nature -– Goode’s feelings, and his femininity, couldn’t be contained. Five years after Goode’s work premiered, scholar/critic David Gere called his study one of “heroic effeminacy.” “29 Effeminate Gestures” became a defining work for a generation of gay men, dance artists or not, who struggled with their identity and coming out in a then more socially and politically hostile decade. Today, at least in many areas of our nation, gay is virtually the new black. If a movie or sitcom doesn’t contain some sort of swishy, gay character, a butch neighbor, or the friendly lesbian couple down the street, well, then how current could it possibly be?

It’s surprising and a compliment to Morgan’s mastery of choreographic structure that “The Measure of a Man,” initially created in 2004, remains vibrant and current. Seen as a companion to Goode’s artistic coming to terms and coming out, Morgan, too, narrates the episodes of a multidimensional life. What’s best though is the chameleon-like facility he has in physicalizing a specific walk, stance, or even just a head nod or shrug. If he weren’t a dancer, Morgan would make a fine living as a character actor of imposing perspicacity. In trying on various identities, which he does readily with help from a wardrobe hung on a clothes line across the back of the stage, he becomes a brusque businessman displaying the broad, confident walk with its alpha male thrust of the chest. Pulling off his starched white shirt and slacks, he morphs into a swishy voguer wearing platform go-go boots, then a prancing danseur noble with a dress-model partner and an accompanying Tchaikovsky waltz. A change of shoulders, and pants, and he’s a heavy-lidded swaggering homey, a knit cap pulled low on his forehead, baggy pants lower on his hips, and some old-school breakdancing and crotch-grabbing moves complete the picture. Each character, distinct and sharply drawn, displays Morgan’s gift for physical mimicry and narrative development. The anticipated ending, as Morgan strips away each of his identities, and his wardrobe, exposes the rawest of emotions, captured in Morgan’s self-flagellating as he whispers “Real men don’t cry.”

It’s surprising and a compliment to Morgan’s mastery of choreographic structure that “The Measure of a Man,” initially created in 2004, remains vibrant and current. Seen as a companion to Goode’s artistic coming to terms and coming out, Morgan, too, narrates the episodes of a multidimensional life. What’s best though is the chameleon-like facility he has in physicalizing a specific walk, stance, or even just a head nod or shrug. If he weren’t a dancer, Morgan would make a fine living as a character actor of imposing perspicacity. In trying on various identities, which he does readily with help from a wardrobe hung on a clothes line across the back of the stage, he becomes a brusque businessman displaying the broad, confident walk with its alpha male thrust of the chest. Pulling off his starched white shirt and slacks, he morphs into a swishy voguer wearing platform go-go boots, then a prancing danseur noble with a dress-model partner and an accompanying Tchaikovsky waltz. A change of shoulders, and pants, and he’s a heavy-lidded swaggering homey, a knit cap pulled low on his forehead, baggy pants lower on his hips, and some old-school breakdancing and crotch-grabbing moves complete the picture. Each character, distinct and sharply drawn, displays Morgan’s gift for physical mimicry and narrative development. The anticipated ending, as Morgan strips away each of his identities, and his wardrobe, exposes the rawest of emotions, captured in Morgan’s self-flagellating as he whispers “Real men don’t cry.”

*****

Of the evening’s newest works, “Compass Point(e)s,” with a moody, contemporary electronic cello score by Ignacio Alcover, demonstrated Morgan’s ability to structure abstract movement in inventive ways. Based on a Lakotan Native American tales and traditions, the work blends ideas of the physical compass points -– north, south, east and west -– with their spiritual manifestations. Not unlike the ancient classical ideas Balanchine drew on for his 1946 work “The Four Temperaments,” Morgan, too, binds the physical and spiritual. Three of the four dancers, including compact dynamo Jason Ignacio, perform in pointe shoes, and the juxtapositions of solos, duets and trios among the four dancers feeds on the refinement of neoclassical ballet. Elizabeth Gahl demonstrated a smooth-handed evenness, while Giselle Alvarez posed a darker presence with her angularity and flexed limbs. Lanky William Smith, the only dancer in slippers, swept in with his long arms and legs, a calming, knowing presence amid some stormy moments, while Ignacio contributed a joyful streak to this mostly sober, though not severe, work.

Borrowing from the club and fashion worlds, “Snapshots,” another premiere, was most interesting for the exaggerated costumes dancer/designer Kyle Lang contributed: shifts with overly popped collars and stiff shoulders, pinafore-like mini dresses, swaths of purple scarves and bright red lipstick. The five vignettes featuring a rotating cast spotlighted primping dancers, in little amuse-bouches -– bite-sized appetizers — that lead ultimately to a one-off punch line, punning on the title. Morgan’s opening, “Pohaku,” with its ancient-sounding chant and drumming, paid tribute to the dancemaker’s Hawaiian roots. A work in progress, it needs an editor’s sharp eye to resolve slackness and gain a clearer sense of the import of performance. Morgan is parsing new ground here, delving into his family’s hula roots, a rich and multifaceted tradition with some compelling stage exponents, among them his cousin, late master hula teacher John Kaimikaua. If Morgan applies the same standards of artmaking here, he’ll find a resonant result.

Published May 28, 2010

© 2010 by Lisa Traiger

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

—

leave a comment