Change and Constancy

Martha Graham Dance Company

Alden Theatre

McLean, Va.

September 24, 2016

By Lisa Traiger

Heraclitus may have said it first, but 20th century modern dance pioneer Martha Graham followed his dictum: “Change is the only constant.” The company the iconic dancer and choreographer founded in 1926 remains the oldest modern dance troupe in the world. In fact, the term “modern dance” was coined by early New York Times critic John Martin seeking a new name for the tradition-breaking choreography Graham began creating in New York in the 1920s.

On Saturday, September 24, 2016, the company presented a program of classic and new works at the Alden Theatre in McLean VA, showcasing the impeccable legacy that Graham company has preserved for generations. But, as Artistic Director — and former Graham dancer — Janet Eilber noted, the company can’t just be a repository for past works, no matter how important. The dancers and the Graham legacy need to reinvigorate with new choreographic pieces. Thus the program on the modestly sized Alden Theatre stage featured works from Graham’s creative heyday in the 1940s along with new works Eilber and her artistic associates have commissioned in recent years, including a recent premiere by Swedish choreographer Pontus Lidberg. The challenge for the Graham company — and many other single choreographer legacy companies — is how to balance the classics with new works — and how to showcase both the legacy pieces and new pieces on a single program without giving one or the other short shrift.

On Saturday, September 24, 2016, the company presented a program of classic and new works at the Alden Theatre in McLean VA, showcasing the impeccable legacy that Graham company has preserved for generations. But, as Artistic Director — and former Graham dancer — Janet Eilber noted, the company can’t just be a repository for past works, no matter how important. The dancers and the Graham legacy need to reinvigorate with new choreographic pieces. Thus the program on the modestly sized Alden Theatre stage featured works from Graham’s creative heyday in the 1940s along with new works Eilber and her artistic associates have commissioned in recent years, including a recent premiere by Swedish choreographer Pontus Lidberg. The challenge for the Graham company — and many other single choreographer legacy companies — is how to balance the classics with new works — and how to showcase both the legacy pieces and new pieces on a single program without giving one or the other short shrift.

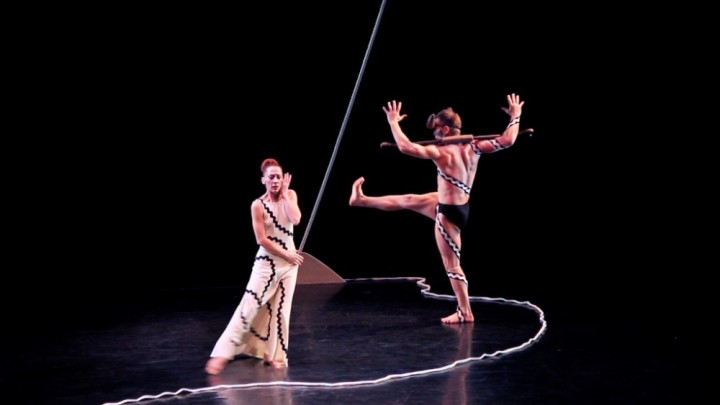

The classic works included Graham’s 1947 “Errand Into the Maze,” from the choreographer’s Greek period. Drawing from the myth of Theseus who journeys into the labyrinth to confront the Minotaur, the piece remains an allegorical study of the internal struggle we all battle in different ways. This stripped down version lacks the Isamu Noguchi sculptural set — a two pronged carved wood structure with a rope-like ladder — and Graham’s original costume designs — a dress with abstract ribbons of rope-like appliqué and the horned headdress of the Minotar. The costumes were lost in the flooding of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Instead, dancer Charlotte Landreau stood firm and determined in a body hugging white dance dress, while overly tattooed Ben Schultz, as the Minotaur, was bare-chested, his arms entwined behind him around a wooden rod limiting his movements. The battle is an internal struggle and what better way to represent that than with the pelvis and spine-centered technique Graham created to tell her elemental dance dramas.

Yet, here and in other works on the program — an essential emphasis was missing in the power or thrust those pelvic contractions can contain that render Graham works metaphorical dialogues in deeply seated battles of life sustaining dimension.

“Dark Meadow Suite” distills highlights from the 50-minute work from 1946 that featured a Jungian inner dialogue and a rhythmically and dynamically complex symphonic recorded score by Carlos Chavez. The abstract piece draws on images Graham collected from her time spent in the southwest. The work, with its spare and classic lines and staccato tremors of cupped hands, feels like a ritual of ancient and mystical purpose. We don’t know for whom these 10 dancers are dancing, but we feel they are dancing for life itself — its preservation and propagation. The men, bold, their bare chests broad as they fill the stage with space engulfing spread-legged hops and cartwheels that end in balanced tilts on one leg. The women are more delicate, their long skirts hiding the rhythmic skittering and stepping of their feet in lovely and complex patterns. If the floor had a layer of sand, the final moments would somehow reveal an exquisitely patterned sand painting. The birdlike flexion of the dancing women’s arms, and the way they hinge and tilt from their pelvic girdles, their bodies like seesaws, demonstrates the power and delicacy these dancers own.

The Graham technique, the once-famed and followed movement structure based on a contraction and release of the pelvis, has lost currency in the 21st century. While the company dancers exhibit the rock-solid abdominal strength, what’s missing is a passionate impetus initiated from an internal force rooted in the pelvis, an expulsion of breath that is felt as the movement grows out of the contraction. But, in truth, Graham has been gone for more than a generation. Modern dance has moved on into various other modes of moving and it’s likely a challenge to preserve something so visceral in a new era that demands different ways to dance.

Of the new works, Lidberg’s “Woodland” felt most finished, but least Graham-like. Commissioned specifically for a score by composer Irving Fine, it features a group of dancers gallivanting in a loose-limbed, very un-Graham-like manner, arms akimbo, torsos free to sway and undulate, breathe and relax, legs and hips sliding easily into the floor and back up to standing again. Most blasphemous of all: the dancers wore socks! A true Graham dancer (I learned from my experiences taking class with old-school Graham dancers back in college) should have enough calluses on the feet to need no footwear whatsoever in the studio or on stage. Barefoot dancing was one of the fundamental principles as modern dance asserted itself in the early 20th century.

“Lamentation Variations” has netted a dozen dances based on one of Graham’s early and most-important solos, “Lamentation.” The work premiered in 1930 and stunned audiences for its gut-wrenching expression of grief in every part of the body. The solo, which Graham and later her surrogates, performed on a wooden bench, features the dancer swathed in purple stretch fabric, contorting and extending her limbs and torso.

The work, projected in silent film clips, showed a young Graham yearning for freedom then allowing herself to be swallowed by her pain in wrenching clarity. The three works drawing inspiration from “Lamentation” included a quirky duet for Anne Souder and Xin Ying, which included physical quotes of some of the memorable moments — a turned in foot, a flat hand wiping an unseen tear from a cheek, outstretched reaches — but ultimately made its own choreographic statement.

Richard Move’s solo for Konstantina Xintara proved the sparest of the three, allowing the dancer to almost imperceptibly cross the stage with a series of reaches and smallish footsteps. Here the choreographer strove for simplicity and constriction of the stage space to just a frontal path, akin to the original’s bench-centric placement. So You Think You Can Dance choreographer Sonya Tayeh’s contribution, a group work with a whispered score, proved the most inscrutable and relied almost exclusively on technical tricks included complicated lifts and maneuvers of the female dancers by their male supports. Frustratingly, as much as these pieces were meant to take inspiration from an American classic, none of the works were able to convey any sense of the all encompassing pain of grief that Graham did so succinctly 86 years ago.

Richard Move’s solo for Konstantina Xintara proved the sparest of the three, allowing the dancer to almost imperceptibly cross the stage with a series of reaches and smallish footsteps. Here the choreographer strove for simplicity and constriction of the stage space to just a frontal path, akin to the original’s bench-centric placement. So You Think You Can Dance choreographer Sonya Tayeh’s contribution, a group work with a whispered score, proved the most inscrutable and relied almost exclusively on technical tricks included complicated lifts and maneuvers of the female dancers by their male supports. Frustratingly, as much as these pieces were meant to take inspiration from an American classic, none of the works were able to convey any sense of the all encompassing pain of grief that Graham did so succinctly 86 years ago.

The program closed with one of Graham’s most beautiful and soaring works, “Diversion of Angels,” created in 1947 to a score by Norman Dello Joio. The work features three distinctive women’s parts, meant to represent three ways we can express love. Leslie Andrea Williams was steadfast as the woman in white, while Xin Ying switched her hips and tilted, her leg raised well beyond her ear, the seductress as the woman in red. Laurel Dalley beamed with happiness and her leaps soared as the woman in yellow.

Throughout the dancers managed ably on a small stage in the intimate Alden Theatre. The last time the company was in the region at the Kennedy Center, we saw far more expansive and passionate dancing; perhaps the dancers felt constrained by the tight space for these grandiose materials. Because there is nothing small nor incidental about even the slightest movement or moment in a Graham choreography. Her clear-eyed vision, her technical demands of a perfect and present body — the dancers’ lines as etched as cut crystal — remind us of the breadth of her contributions to the artistic conversation occurring among dancers, choreographers, poets, composers and painters of the mid-20th century. And it reminds us of what a treasure it remains that these works are still lovingly maintained while the company strives to find new 21st century voices that echo Graham’s clarion call.

Photos: “Errand into the Maze,” Martha Graham Dance Company

“Lamentation Variations” by Sonya Tayeh, photo by Christopher Jones

This review originally appeared in the online publication DC Metro Theatre Arts and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2016 by Lisa Traiger

leave a comment