New Season: New Hope?

District Choreographer’s Dance Festival

Dance Place, presented at Edgewood Arts Center, Brookland Arts Space Lofts Studio, Dance Place Arts Park, Dance Place roof, offices, and Cafritz Foundation Theater

Choreography: Kyoko Fujimoto, Dache Green, Claire Alrich, Shannon Quinn of ReVision Dance Company, Gerson Lanza, Malik Burnett, and Colette Krogol, and Matt Reeves of Orange Grove Dance.

Washington, D.C.

September 9 – 10, 2023

When Dance Place opened its season each September, it heralded a surfeit of dance performances for the next 11 months. In fact, the nationally known presenter for decades offered up live dance performances across genres from modern to African forms, tap, bharata natyam (a classical Indian form), hip hop, flamenco, performance art, post-modern, raks sharki (belly dance), salsa rueda, stepping, even contemporary ballet, to mention just a few. Dance lovers could be assured of a show nearly every weekend of the year from September through June, with a smattering of performance options spread across the summer. Most years during its heyday, Dance Place presented between 35 and 45 weeks of dance annually, from both regional companies and national and international artists. Among those were first D.C. performances (pre–Kennedy Center invitations) from David Parsons Dance, Urban Bush Women, Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, Rennie Harris/Puremovement, Blue Man Group, and dozens of others. And along with well-curated programming, the organization offered professional and recreational studio classes in modern dance, West African dance and other forms, and a free summer arts camp for neighborhood children.

The feat, presenting more dance annually than the Kennedy Center, happened under the indefatigable visionary leadership of founding director Carla Perlo and her co-director Deborah Riley. Since they stepped away from leadership in 2017, the nationally renowned organization has struggled to find its new identity under two different artistic directors, an acting director, a global pandemic, and presently little institutional knowledge regarding the organization’s outsized influence in the dance world.

But season openings always offer a fresh opportunity to hope.

The 2023/24 season marks Dance Place’s 44th year. September 9 and 10, the organization chose to continue a tradition of showcasing locally based artists in new and recent works, which dates back to the Perlo and Riley era, and “post-pandemic” Christopher K. Morgan named the season opener the District Choreographer’s Dance Festival. This year, Dance Place and seven choreographic artists showcased not only their works but also the studio, performance, and space assets the organization manages and has access to along 8th Street NE, hard by the Metro and railroad tracks, just a short walk from Catholic University.

The afternoon began at Edgewood Arts Center, a community room used for weddings, parties, classes, and the like. Choreographer Kyoko Fujimoto, who also holds a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, fashioned a contemporary ballet quartet featuring point work and lifts, punctuated by the angularity of 90-degree elbows and knees — perhaps an ever-so-slight nod to Balanchine’s mid-20th-century neo-classicism. The work, “into the fields,” was meant to recall the experience of a medical MRI. That was evident in the horizontal crossings of single dancers rising and falling like pointed peaks and valleys of a heart monitor readout. It could also be heard in Caroline Shaw’s music from “Plan & Elevation” and another musical sequence from V. Andrew Stenger and Fujimoto. The stark black biker shorts and white tops provided an ascetic look for dancers Sara Bradna, Ian Edwards, Max Maisey, and Sophia Sheahan.

The audience was then led down the street to a Brookland Arts Space Loft studio for performer/choreographer Dache Green’s “Evolution(ary).” In the tight, bare studio, Green, long, lean and powerful, struts forward in chunky black heels, jean shorts, and an olive green trench coat. Viola Davis’ resonant voice is heard in her famous 2018 speech for Glamour magazine: “I’m not perfect. Sometimes I don’t feel pretty. Sometimes I don’t want to slay dragons … the dragon I’m slaying is myself …” To that, and then to a Beyonce-heavy score — “I’m That Girl,” “Church Girl,” “Thick,” “All Up in Your Mind,” peppered with other artists like Kentheman, Inayah Lamis, and Annie Lennox and the Eurhythmics — Green grabs center stage like a model on a catwalk, owning the space and moment as he poses, struts, bumps and grinds, vogues and twerks, all the while lip-syncing. It’s a public and private confessional about discovering and owning one’s personal story with power and self-love, acceptance, and being fierce.

Back outside in the partly cloudy afternoon, if one didn’t look up, you’d miss ReVision Dance Company’s Amber Lucia Chabus and Chloe Conway, clad neck to ankle to fingertips in highlighter pink and highlighter green respectively, poking a jazz hand, leg, or foot out from the Dance Place Roof. Choreographer Shannon Quinn let her two dancers loose on the roof to play with each other and with the viewers two stories below. I recalled film and photos of choreographer Trisha Brown’s 1971 “Roof Piece” and loved this nameless piece d’occasion all the more for its nod to post-modern dance history, while not taking itself too seriously, including playful moments and silly mime as the duo stepped down to disappear, then pop up seconds later in another location.

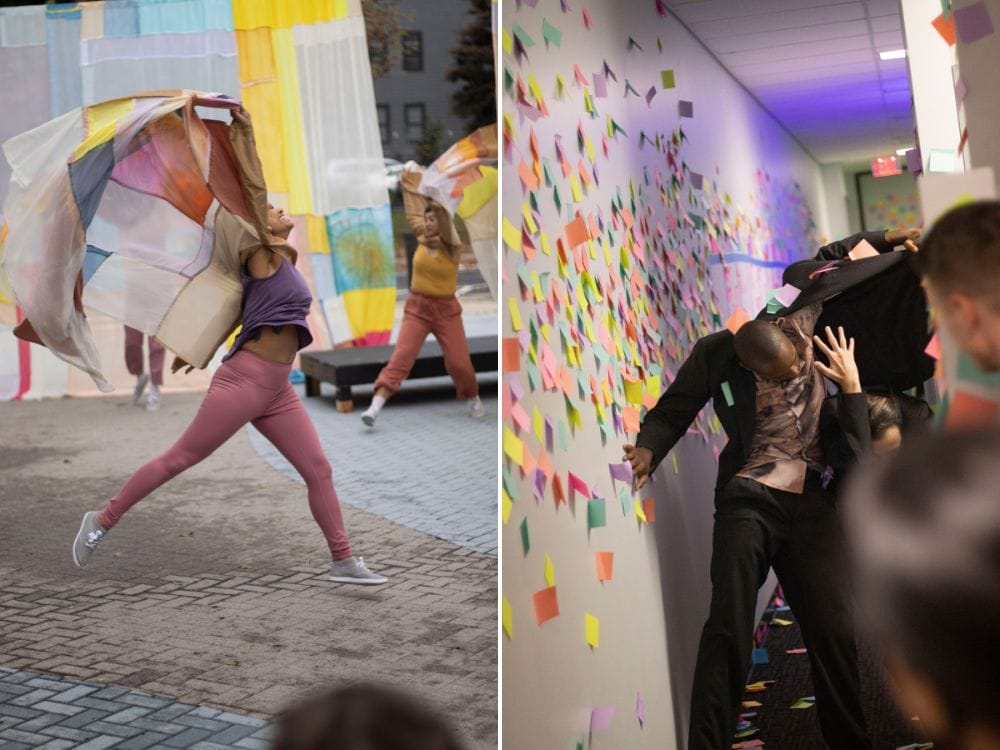

Claire Alrich’s “scenes from an elevator ascending” spread out on the Arts Park, a former city easement of land Perlo developed into a multi-use space for the community to congregate between Brookland Arts Lofts and Dance Place. With a set of stitched-together curtain-like panels and flowing cape-like tunics in mauve, mustard, and cantaloupe colors designed by Alrich and Mara Menahan, the three dancers stretch their arms to work the expanse of the costume. The work feels like an organic transformation in process. I was reminded of the caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly cycle, particularly as the dancers gently left the space walking away down Kearny Street as Santiago Quintana’s score faded.

“Paper Jungle” was meant to be a ten-minute experiential piece for ten people at a time to walk through the upstairs office cubicles of Dance Place. Technical delays kept groups waiting, but Orange Grove Dance, helmed by choreographic and design partners Colette Krogol and Matt Reeves, is consistently worth a wait. Entering the tightly constricted hallway, walls scattered with Post-it notes, “Paper Jungle” featured dancers Robert Rubama and London Brison joined by Reeves, who at times carried an open laptop on record. Audiences waiting in the downstairs lobby could watch — spy — on happenings upstairs on the large multi-picture video screen. Three men clad in slim black suits unfurled muscular, manic motion exploding along the cubicle corridor with bursts as legs and arms flung akimbo. The pressure cooker feeling of too much paper, too much movement, too many people, and sounds in the constrained space felt like a bad day at the office. Musicians Daniel Frankhuizen on cello and synthesizer and Jo Palmer on percussion compounded the atmosphere. “Paper Jungle” resonates with the overstimulated workloads and life loads so many carry, but, even so, with so much to see in such a short time span, it was hard to depart.

After a break the evening included two solos in the Dance Place Theater: percussive tap dancer Gerson Lanza’s “La Migra” explored his Honduran roots and emigration journey, while Malik Burnett’s “In Here Is Where We’ll Dwell” tackled his personal spiritual journey. Both works were personal testimonies to triumph over adversity. Lanza built on ancestral connections to traditional Africanist footwork in bare feet on an amplified wood tap board, pounding out syncopated bass and treble notes before donning brown leather tap boots for a soliloquy in sound. Burnett entered from the lobby hooded — a monk’s robe or a hoodie, in the half-darkness it’s both. Video clips draw on celebrated inspirational personalities from Oprah Winfrey to Amanda Gorman, Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, while the dancer draws himself out to expansive reaches highlighting a spiritual sense of striving for redemption. The work concludes with a slow walk upstairs through the audience to a fading light.

The festival format program, which began at 4:00 p.m., ran through about 5:30 p.m. with a break before the final two works went up in the theater, finishing up shortly after 8:00 p.m. For dance adventurers and dance lovers, this was full immersion; others may not have been so satisfied.

Finally, while this District Choreographer’s Dance Festival heralds a new season, Dance Place’s programming remains truncated. Some months contain just a single run and later in the season multiple weeks are booked, with most presentations being for a single performance rather than a two-show weekend. The organization suffered multiple blows with the retirements of its founding leadership, and turnover in its replacements, along with the ongoing challenges of the pandemic and post-pandemic recovery. Six years along, Dance Place is still finding its footing. It may never be the same. We can only hope the new leadership team remains committed to building on past successes and supporting dance and dancers for generations to come.

This review originally appeared September 13, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Romp and Rumination

Choreographer Sarah Beth Oppenheim scales a moving and storage warehouse

‘Many Extra Only More’

Heart Stück Bernie

Extra Space Storage, 2800 8th Street NE

presented by Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

July 7-8, 2023

By Lisa Traiger

It’s been a while — a long while — since I saw a locally produced, original choreographic work that wowed me. Saturday night July 8, 2023, I was wowed. As I sat on the Franklin Street NE bridge pedestrian walkway, facing the rectangular industrial Extra Space Storage building on 8th Street, waiting for the sun to set, I donned “silent disco” headphones and bobbed my head to the beat. The music, edited by Oliver Mertz, ranged from Bela Bartok to Ethiopian musician Mulatu Astatke to pop band Animal Collective and Ukrainian group DakhaBrakha to name a few of the eclectic choices. Traffic whizzed by on the bridge, leftover illegal fireworks boomed in the distance, a siren screamed, and on railroad tracks parallel to 8th Street, trains rumbled by.

As the sky darkened, the 20 windows of Extra Space Storage brightened, then music pumping, at once 40 dancers filled the 4 x 5 grid of windows, bopping in brightly colored separates of red, yellow, and orange. Many Extra Only More unfurled as a massive and wow-inducing site-specific piece from the marvelously imaginative and generative mind of Silver Spring–based choreographer Sarah Beth Oppenheim, who leads ten fearless dancers of her company Heart Stück Bernie. Many Extra Only More begins like a romp. You can’t help but smile and wish you were up there dancing with them.

But there they are, each in a separate window box, brightly lit, smiling. Together and alone. And soon the primary colors and vivid playfulness, quirky, tick-like gestures and poses, take on moodier shadings. It’s not so long ago, as memory serves, we were all living in and in front of computer-lit boxes, isolated in our homes but distantly together in our Zoom rooms at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Oppenheim’s choreography does those quick tone shifts often, and well. She’ll make a ridiculously cute set out of cardboard cut-out shapes — oversized paper-doll dresses, puffy armchairs, yellow suns and crescent moons, rainbows and stars — or reams of paper with childlike drawings or PowerPoint-like instructions for the audience. She crafts as if Martha Stewart taught kindergarten and her dances emote an unspoken language filled with silent action verbs; dancers skip and hop, slink and saunter, shimmy and slither, ooze and vibrate, twitch and punch, bounce and breathe. Oppenheim has some of the quirky bright cheerfulness along with the millennial zeitgeist of sitcom actress and musician Zooey Deschanel that belie her own bright smile and vivid thrift store wardrobe.

Oppenheim has been an artist-in-residence at Dance Place — the producer of this outsized, and outside, evening — and has presented work on its stage. Her choreography has also been seen in gardens and galleries — including the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing — alleyways and storage closets. She sees dance in life’s most ordinary moments and elevates those mundanities with movement and visions of how living and dancing deeply intertwine. Her work in the community with its light and dark tones and its serious fun is her way of spreading the gospel of creative thinking to the masses.

Saturday night Many Extra Only More addressed multiple ideas in its 50 fast-moving minutes. Audiences had to come to terms with the caveat that they wouldn’t see everything. A pre-show announcement noted that no spot would allow viewers to see it all completely, and they were welcome to move around throughout the show. Sitting on what I believed were prime “balcony seats” on the Franklin Street NE bridge made me wish I was below, across the street at the Dewdrop Inn looking head-on at the dancers filling the windows. But I was quickly reminded of Merce Cunningham’s Events where dancers populated public spaces and you couldn’t catch it all, intentionally. Oppenheim’s work also nodded to another mid-20th-century modern dance choreographer, Anna Sokolow, whose acclaimed Rooms explored the isolation individuals felt in their massive apartment buildings: living in tight clusters, but each alone in their singular rooms. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades — found objects displayed as art — also came to mind with the readymade non-theatrical setting and set pieces — ordinary stuff you would find in a storage unit. Or maybe that’s a nod to the hit show Storage Wars. No matter, Oppenheim knows what she’s doing at every moment of this large-scale romp and rumination.

Many Extra Only More spooled out episodically in those window frames, vertically, horizontally, diagonally, and randomly. Oppenheim — with rehearsal assistance from Nancy Bannon and Kourtney Ginn — realized a choreographic feat in spatial organization navigating the windows like a Rubik’s cube master. Dancers shifted in groups, individuals, sometimes carrying in props, crafty cutouts, even at one point a striped sofa. Lighting by Kelly Colburn and Mark Costello used colored gels on the intense fluorescent warehouse lights, among other large-scale tricks, to shift mood and tone during the vignette-like sequences.

Moments of group synchronicity — even as dancers eschewed complete unison — conveyed celebration; a series of folk-dance–like chains and circles reminded me of a wedding or bar mitzvah. Then smaller configurations of two, three, or five reflected relational and interactive conversational moments. One dancer — Sadie Leigh — donned a green striped robe — like the green garage-like doors of the storage units — on which a collection of paper cutouts of overflow detritus were pinned: a lamp, a chair, an end table, a candlestick. Metaphorically, the choreographic structure with this oversized cast reflects the overstuffed lives so many Americans live today — homes filled with too many dishes, toys, books, sofas, and lamps, and not enough Marie Kondo self-reflection to discard what isn’t joyful. Instead, those excesses of our lives, which we can’t let go of, become a boon for the storage industry. And a reflection of the baggage we hang on to.

This is seen in moodier sections of confrontation, dancers battling as we watch — becoming voyeurs looking in from the outside. A song comes on with a violent thread as slow-motion fists and clawed hands are drawn out. A woman is splayed across a table — others manipulate her. Across the way, two dancers run themselves into the windows, again and again. Suddenly, nothing is bright or fun, sunny or sweet. Cute sun and rainbow cutouts taped to windows can’t whitewash the discord and pain surfacing in this glass-housed world Oppenheim has wrought.

The mood modulates — like life — in shifting vignettes. We follow the dance modulate from joy to pain, playfulness to violence, happiness to despair — and, finally, at the end, back to another dance-off, each dancer in her window grooving to the beat, then departing a few at a time, only to reappear on the street in front of the warehouse. The earphones still blasting music, the disco still silent, but then everyone has clumped together, and some audience members join the group. If Oppenheim wished for a big, bold, extra, supersized statement piece about the simple yet profound ways dance affects us, changes us, makes us think, moves us, and makes us move, she did it.

In recent years, we’ve seen some tectonic shifts in dance in Washington, D.C., from the departure of MacArthur “genius” grantee Liz Lerman a dozen years ago, to the retirements of Dance Place co-directors Carla Perlo and Deborah Riley in 2017, to the departure of Septime Webre from the Washington Ballet that same year, and the recent untimely losses of Michele Ava, cofounder of Joy of Motion, and Melvin Deal, founder of African Heritage Dancers and Drummers. Just this year, the service organization Dance Metro D.C. closed down. Dance in the region has been on unsteady footing. Even before the pandemic shut down studios and companies for months and months, including some that didn’t survive, we were seeing fewer dance presentations in smaller venues beyond the Kennedy Center’s large stages. Dance Place’s once-weekly performance presentations have diminished to one to two performances a month.

This, Oppenheim’s largest and most complex work to date, was initially conceived in 2017, but delayed by that global pandemic. The complexities of the large working business site, technical requirements, and a massive cast for a locally produced dance company demonstrate that creative forces continue to percolate in D.C.’s homegrown dance community.

So Many Extra Only More bodes well for the future. Let’s hope Dance Place and the D.C. metropolitan dance community can take inspiration from Oppenheim’s extra-large, many-dancer production that shouts “More” with its collection of a strong cadre of young and veteran dancer/choreographer/creatives in its cast.

Featuring Heart Stück Bernie Dancers

Emily Ames, AK Blythe, Amber Lucia Chabus, Terra Cymek, Kate Folsom, Raeanna “Rae” Grey, Sadie Leigh, Patricia Mullaney-Loss, Nicole Sneed, Kristen Yeung

with

Claire Alrich, Katherine Berman, Lauren Bomgardner, Lauren Brown, Jennifer Cinicola, Sarah Coady, Annika Dodrill, Allison Grant, Safi Harriott, Jocelyn Hartman, Faryn Kelly, Betsy Loikow, Julia McWest, Bretton Mork, Simone Nasry, Annie Peterson, Sarah Raker, Jane Raleigh, Alison Waldman, Berea Whitley

and

Elizabeth Barton, Jadyn Brick, Annie Choudhury, Lauren DeVera, Celina Jaffe, Emilia Kawashima, Luisa Lynch, Chitra Subramanian, Zoe Wampler, and Janae Witcher

This review originally appeared July 10, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

In Memoriam: Alexandra Tomalonis

Dance critic, scholar, historian, educator, and mentor Alexandra Tomalonis died April 7, 2023. I met Alexandra in the early 1980s, when I was a college dance and English major with aspirations to write dance criticism. Shortly after I graduated, Alexandra invited me to write for her self-published magazine — Washington DanceView — which at that time came out quarterly. She took me under her wing, frequently inviting me to join her at Kennedy Center ballet performances. I learned much from her during our intermission conversations with what I called the D.C. critics’ huddle, which included Mike and Sali Ann Kriegsman, George Jackson, Suzanne Carbonneau, Pamela Sommers and Jean Battey Lewis on occasion. I was in awe of these seasoned dance critics and learned much from their writings and their conversations, particularly their recollections of performances I didn’t see or their reports of dance in New York and other cities. Alexandra introduced me to the Dance Critics Association, where I ultimately became president. During the hard 2020 summer of the Covid-19 pandemic, we had an almost weekly phone call where our conversations meandered into family histories, politics, and the art-politic confluence. I wish I had continued those calls when I got busy again.

In April 2013, when Alexandra was teaching ballet history and aesthetics at the Kirov Academy of Ballet in Washington, D.C., then-executive director Martin Fredmann asked me to interview her for the school’s magazine. The article is no longer on the Internet, so I share it below as I reflect on the major influence Alexandra had on Washington’s metropolitan area dance community, as well as on ballet and dance nationally and internationally, through the many students she taught and through her graceful writing. May her love of dance and the written word continue to inspire us.

Alexandra Tomalonis

By Lisa Traiger

Dance critic and author Alexandra Tomalonis has been a fixture at the Kirov Academy of Ballet for a decade now. Over the course of that period, she has taught an estimated 120 to 150 students ballet and art history, aesthetics and the popular favorite “The Great Ballets, 1 and 2,” covering the art form’s 19th- to 21st-century masterworks. But Tomalonis has imparted much more than names, dates and librettos to her students, many of whom have gone on to become professional dancers with companies throughout the world.

Just ask 2010 academy graduate Kiryung (Kiki) Kim, currently a member of the Studio Company of the Gelsey Kirkland Academy of Classical Ballet in New York. “She told us many stories and [a] few stuck with me,” Kim wrote via email recently. She recalled Tomalonis’s story about a recent graduate, an excellent dancer who had auditioned “everywhere” and made it to the final cut at each audition, but had not received a contract, instead ending up at a trainee program. “However, the next year she did not lose hope and auditioned again, getting a corps de ballet contract with a prestigious European ballet company that she wanted to dance in.” Tomalonis, Kim recalled, said that “sometimes things don’t work out, but if you keep working, your time may come, too.” Lesson learned.

As important as the intensive daily program of ballet technique classes and rehearsals is at the school, academics, too, remain a mainstay of what makes KAB so special. Tomalonis, as academic director since 2010, and a teacher here since 2003, has set the course along with the artistic department for a cadre of well-prepared and intelligent dancers, many of whom are making their way in the highly competitive and professional ballet world. Others have gone on to college, some later joining company ranks, others finding work in professions outside the dance field. She believes fully that the best dancers are the most well-educated. Beautiful feet, a high arabesque, and a refined ballet line might get a dancer noticed, but company directors these days want far more – dancers who can think, understand and express are more likely to succeed these days. For Tomalonis that means inculcating her students in ballet history, art history, and the canon of the great ballets.

“These kids will all go to college, we hope,” she said. “I just don’t want them to go at 18, but as dancers they’re going to be dealing with people who went to college.” That’s why her courses cover more than the basics. In high school facts are emphasized, but college, Tomalonis said, is where students learn how to put ideas together, synthesize material and begin to think for themselves. That’s what she hopes to achieve in her advanced classes, particularly Aesthetics and Ballet History. “The last two years I try – and all the teachers here do — to give them more college-like experiences so they can put it together and that’s so exciting.”

“From Ms. Tomalonis, I learned how to learn,” said Carinthia Bank. “And that is more useful than whatever actual facts I might be able to recall.” Tomalonis agrees, premiere dates and other information can easily be looked up. Thinking and responding to deeper questions about why a character might dance a specific way require more thoughtful consideration. Presently a dancer with the Donetsk Ballet of Ukraine, Banks had Tomalonis as a teacher in various summer-program classes from 2006 to 2008, at which time she became a full-time Kirov student.

Tomalonis’s own introduction to ballet was somewhat serendipitous. “I actually took modern dance in college because, first, we had to for a phys ed requirement, and I was also interested in it. But I had not seen any ballet.” She grew up in a family that valued intellectual rigor and enlightened discussion. She studied piano and attended the theater as a child, but her first ballet experience came at about age 26.

“A friend told me Rudolf Nureyev was coming,” she said. “I said, ‘Oh, he’s famous, let’s go see him.’ So we went and the curtain went up on ‘Marguerite and Armand’ … and I loved it.” She went back for more. “With all of my cultural education … I realized I knew nothing about a whole art form. That’s when I started reading and reading and reading.” After a semester in a dance writing class with late Washington Post dance critic Alan M. Kriegsman, she began reviewing for the Post and later her own magazine, Washington DanceView, which eventually evolved into the online DanceViewTimes. She also founded the online discussion boards Ballet Alert! and Ballet Talk for Dancers.

“I didn’t set out to be an historian,” she added, “I just wanted to know how it happened, so I just kept reading.” And in those heady dance boom days of the 1970s, The Kennedy Center, which had just opened, was featuring weeks of ballet companies from around the globe and Tomalonis rarely missed a performance. Soon her fandom grew into something deeper as she explored ballet history. “When I started writing,” she said, “I became more interested in where it came from rather than who was dancing. … I had favorite periods: Ballets Russes, then it was the Royal Ballet, then modern dance. I loved Martha Graham. I love people who try to go back to the beginning and try to do it right, which [Graham] was dong with pre-classical dance forms. And I loved that she took on the Greek myths.”

In her Ballet History course, Tomalonis’s students create a timeline of the art form and she’s always amazed at the creativity her students put into the project – one made a clock, another a tree with roots and branches. She loves to have students compare different versions of a work and study different dancers performing the same choreography, it opens their eyes to understanding the variety and expansiveness in the ballet world. She admitted that her teaching has evolved over her decade at KAB, but her goal has remained. “First I certainly want them to know ballet history. And second, certainly with the Great Ballets, I want them to see how ballet works and looks around the world … [KAB students] are very, very much focused on their technique. And I think they should be, but I think they should be able to see other schools [outside of Vaganova training] and know that a different way of doing an arabesque isn’t wrong. It might just be English. Or that the Paris style is very precise. And Bolshoi is different than Mariinsky.”

Adrienne Bot, a senior this year, said, “The most difficult or challenging aspect of Ms. Tomalonis’s class is that she wants us to be able to articulate not only that we liked or disliked what we read or saw, but why we liked or disliked it.” Bot has had Tomalonis as a teacher from 2011 to 2013 in Great Ballets, Ballet History, and Aesthetics. After graduation Bot has her sights set on landing a company contract where she can continue to grow and learn. From Tomalonis she said, “Her challenge to us is to learn about ourselves, to explore more than just a superficial level of who we are and why something appeals to us or not. It sounds easy, but that is deceptive.”

Kim, a former student, appreciated not only Tomalonis’s depth of knowledge but her insider stories. “She would share many anecdotes about famous dancers, choreographers, and companies,” Kim said, because she spent much time researching a book on Royal Danish Ballet dancer Henning Kronstam (Henning Kronstam: Portrait of a Danish Dancer) and knew many first-hand accounts from dancers in the ballet world. “She gave us the [back] story of [many choreographers’] philosophies on dance.”

Bot added, “Her passion and love of ballet is contagious.” A generation of KAB students certainly thinks so and has benefitted from that knowledge and passion.

Lisa Traiger writes on dance and the performing arts from the Washington, D.C. area and is proud to name Alexandra Tomalonis as one of her mentors.

Originally published by the Kirov Academy of Ballet, April 2013.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Resolute

United Ukrainian Ballet reinvigorates ‘Giselle.’

While their homeland is fighting for its survival, these dancers rallied to create a unified company in just months, and that sense of urgency is palpable.

Giselle

United Ukrainian Ballet

John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Opera House

Washington, D.C.

February 1-5, 2023

By Lisa Traiger

Betrothal, betrayal, and the ultimate forgiveness: these are the themes that shape Giselle into one of the beloved ballets of the Romantic canon. This week exuding resilience, courage, and patriotism, an ad hoc ballet company named the United Ukrainian Ballet re-invigorates this warhorse of a ballet, while demonstrating the indomitable spirit of the Ukrainian people.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine disrupted daily life, including the performing artists and ballet dancers of many of the nation’s opera houses. A ballet dancer’s career is brief, and the inability to train and perform can make it briefer. While many female dancers fled their homeland, amid a barrage of Russian strikes on cities and towns in Ukraine, including its capitol, Kyiv, men were conscripted to fight. Ballet company leaders requested that male dancers be released from military service in order to serve the Ukrainian people through their art. It was granted.

Sixty dancers from Ukraine and around the world, including the National Opera of Ukraine, Doinestk Opera House, Kharkiv National Opera House, and Donbas Opera, to name a few, found their way to the Hague, Netherlands. They have been joined by Ukrainian nationals, among them Cristina Shevchenko from American Ballet Theatre and Kateryna Derechyna from the Washington Ballet.

Together this ad hoc group is breathtaking in conception and physical prowess, rallying to create a unified company, which can take years or decades, in just months, while their homeland is fighting for its survival. That sense of urgency, particularly in act II, is palpable and came to a pinnacle with the bows and curtain calls on opening night. Lead dancers Shevchenko and Oleksei Tiutiunnyk took center stage draped in a vibrant blue-and-yellow banner stating “Stand with Ukraine,” followed by Russian-Ukrainian choreographer Alexi Ratmansky proudly stretching the Ukrainian flag above his head.

The journey to Giselle and the Kennedy Center wasn’t easy but was eased by fortuitous circumstances. A former conservatory-turned-refugee center in the Hague became the haven and home for this new Ukrainian ballet troupe. Last year the company performed in London, Australia, and Paris; this relatively late booking at the Kennedy Center Opera House is the only U.S. performance, and it only happened, according to a Kennedy Center staffer, when the cancellation of the National Ballet of China caused a hole in the ballet series. United Ukrainian Ballet filled the bill nicely.

When choreographer Alexi Ratmansky heard the Ukrainian dancers had taken refuge in the Hague, and they needed a ballet, he didn’t hesitate. The renowned ballet maker and stager, while born in Leningrad, has a Russian mother and a Ukrainian father; his heart, he has said, fully beats for Ukraine.

Ratmansky gifted this ingathering of fleeing dancers a fully realized and reinvigorated version of the 19th-century Romantic classic. The result: a refreshingly compelling evening that draws from historical precedents, which Ratmansky unearthed in research into archival notes and accounts of the ballet that originated in 1841 in Paris. He’s done this before with The Sleeping Beauty, among other classics.

The story of Giselle, a vivacious young woman besotted by Albert (Albrecht or Loys, in some versions), who is a nobleman slumming as a villager, is an oft-done standard in the ballet canon. A stable of the repertoire, Giselle offers up two acts of elegant dancing, along with the pathos of heartbreak when Giselle discovers her suitor isn’t who he claims and is engaged to a noblewoman. As a jilted bride who dies before her wedding, she is resigned to haunt the forest as a ghostly spirit called a Wili. The second “white act” — in the midnight forest — features these ghostly beautifully terrifying Willis, clad in shimmery, bell-shaped gossamer tutus. But their beauty deceives: having been jilted by their fiancés, they haunt the forest to take revenge on single men whom they dance to their doom.

While basing the work on choreography by 19th-century ballet master Marius Petipa, after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, from the early 19th century, Ratmansky resuscitates what can, depending on the company, be a staid experience aimed at ballet stalwarts. Here he returns to mime passages that often receive short shrift, particularly by American troupes. The codified gestures typically express basic feelings of love, fear, promises to marry, and a passage that presages death. This version allows Berthe (Olena Mykhailova as a fierce helicopter mom), Giselle’s mother to “speak,” miming her worries and the spooky backstory of what happens to young ladies who disobey their mothers’ wishes and court someone in secret. Her sharp gesture as her forearms form a cross pointed to the ground rings true for all the mothers of teenagers over millennia who declared, “Be careful or you’ll find yourself in an early grave.” Sergii Kliachin’s Hilarion, Albert’s rival for Giselle’s attention, broodingly eyes the happy couple as he plots his revenge in order to win Giselle’s heart. He’s a bit like outsider Judd from the Rogers and Hammerstein golden-age classic Oklahoma!

Throughout both acts, small and large details provide for a more compelling Giselle than I’ve seen in decades of dance-going. Some, I’m not sure are fully necessary, like shifting the first-act demi soloists’ variations during the villagers’ variations to a more formalized grand pas de deux structure. For those who know, the four-part grand pas de deux is typically reserved for four-act classical ballets and allows the principal ballerina and danseur to demonstrate their technical virtuosity.

In act II, before the Wilis appear, a bumptious forest scene features a group of drinking buddies out at night for a lark. This “bro” moment, when they toast each other and nearly bump fists, feels like any testosterone-filled Saturday night at the pub. Then Hilarion, and later Albert come upon them. A distant bell chimes midnight and the thought of ghosts makes them scatter. The Wilis, led by the imperious Myrtha, fearsome mean-girl Elizaveta Gogidze, dart and even fly across the stage as they gather to dance under the watchful eye of their tall leader, their translucent veils whisked away as if by magic.

Ratmansky has furthered beautified and given weighted meaning to this white act, through his sensitive staging and floor patterns. The dancers gather, tracing circles and lines and, most notable, forming themselves into the shape of a cross as Giselle’s fresh grave stands to one side. Other intriguing moments include the fight-club-like rounds of dancing Albert is compelled to do at the behest of Myrtha, her gaze steely, her arms crossed across her chest. He is pushed and pulled up and down a diagonal line of Wilis until he collapses in exhaustion.

Shevchenko imbues her Giselle with a vivid personality, she’s girlish but a bit of an adventurer in the first act. Often Giselle is scolded by her mother for her weak heart; this Giselle projects a feisty spirit. It’s no wonder that Count Albert falls for her vivacity. Tiutiunnyk, lean and leggy, is not nearly as caddish as many Albert/Albrechts I’ve come across. His leaps soar, suggesting he’s used to a larger stage than the Opera House, and he’s a fine partner to Shevchenko, guiding her gently into balances. Shevchenko, who returns to the Opera House later this month as Juliet in her home company American Ballet Theatre’s Romeo and Juliet, has a lovely sense of ballon, or rebound, which is perfect for the many versions of the “Giselle step,” a gentle hop on one foot as the other leg opens and closes at the ankle like a hinge. It’s her signature dance — made for a 15-second TikTok video.

The Birmingham Royal Ballet (Great Britain) lent its sets and costumes for this production. Act II’s Wilis shimmer in moonlit colors of palest gray-blue rather than the traditional stark white Romantic tutus, which only Giselle wears.

The new staging of Giselle’s final moments, when she forgives Albert, completely shifted the demeanor of the ballet. Giselle settles herself into a raised berm or hillock at the corner of the stage — resigned to her fate as a jilted woman, foretold by her mother in act I. As Albert approaches her aggrieved one last time, she lifts her head and shoulders, and gestures to him — the sunrise in the background showing the royal retinue arriving — to go to his original fiancée Bathilde. Giselle earns her wings forgiving and releasing her beloved. She will remain a Wili, resigned to a ghostly life only to arise at midnight in the forest.

In a Giselle filled with moving moments, this final gesture was deeply felt and resonated with the resilient and unstinting performances of the company. At the final curtain call, the company stood together, shoulder to shoulder, as the orchestra struck up the Ukrainian national anthem:

The glory and freedom of Ukraine has not yet perished

Luck will still smile on us brother-Ukrainians.

Our enemies will die, as the dew does in the sunshine,

and we, too, brothers, we’ll live happily in our land.We’ll not spare either our souls or bodies to get freedom

and we’ll prove that we brothers are of Kozak kin.

This review originally appeared on DC Theater Arts on February 3, 2023, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Love Is in the Air

The Look of Love

Mark Morris Dance Group

John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 26-29, 2022

By Lisa Traiger

One-time maverick choreographer Mark Morris is now mature enough to collect Social Security. In another millennium, way back in 1985, his Mark Morris Dance Group made its Kennedy Center debut upstairs in the Terrace Theater. Back then he had long brunette ringlets of curls, a sensitive and knowing ear for music, and a crafty way of interlacing modern dance with everything from Bach to country, East Indian raga to punk. And it worked. His young company of ten dancers exuberantly tackled the insouciant steps that were both smart and sly.

Since, Morris and his company have become institutions in the oft-precious modern dance world. He has been back to the Kennedy Center many, many times. Through Saturday, October 29, 2022, the company is ensconced at the Eisenhower with Morris’ newest piece, The Look of Love, an hour-and-change work set to 1960s and ’70s pop icon Burt Bacharach’s hits.

The Look of Love comes on the heels of the company’s last Kennedy Center show in 2019, when it brought Pepperland, an easy-listening, brightly colored homage to the Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. Back in ’85 at his first DC program, the company danced to Vivaldi, Bach, and the Violent Femmes. Nothing was experimental, but it all felt fresh, performed with frisson. Morris’ recent forays into baby boomer songbooks align well with the Broadway retreads of jukebox musicals.

Morris’ followers know well his facility with musicality and his requirement to always use live music. At the Eisenhower Theater, the company music ensemble featured music arranger and long-time MMDG collaborator Ethan Iverson on piano, and gorgeous-voiced Marcy Harriell rendering Bacharach’s songs — with most lyrics by Hal David — in thoughtful jazz renditions, with backup vocals by Clinton Curtis and Blaire Reinhard, joined by Jonathan Finlayson on trumpet, Simon Willson on bass, Vinnie Sperrazza on drums. The ensemble plays in the elevated orchestra pit, and Harriell, glamorous in her bare-shouldered dress, often turns to sing to the dancers on stage.

Raised in Forest Hills, New York, Bacharach, 94, attended the same high school as Simon and Garfunkle and Michael Landon. A child piano student, he favored jazz and later in California studied with mid-century modernist composers Henry Cowell, Bohuslav Martinu, and Darious Milhaud, whom he cites as his greatest influence. But it’s songs like “Alfie,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” and “What the World Needs Now” that defined pop music for the 1960s and ’70s generation. Lively, singable stories of love, longing, loss, and connection, with an occasional shadow tossed in. Morris selected 14 indelible songs from the Bacharach songbook beginning with a jazzy instrumental riff on “Alfie” — surely many heard Dionne Warwick singing in their heads.

On the empty stage a few scattered folding chairs stand — one of the cliches of modern dance is the chair as a prop. It suggests the choreographer needs a device and that’s all that’s available in the rehearsal room.

The dancers enter to strains of the feel-good anthem “What the World Needs Now,” clad in sunny pastel tunics, shorts, pants, or dresses color blocked in melon-y orange, lime green, sunny yellow, ochre, and starburst pink. Morris is a master of manipulating simple movement patterns and weaving them into complex spatially shifting phrases. Fans of folk dance will recognize standard footwork featuring stomps, grapevine, and triplet steps in converging and separating lines and circular paths. Another favorite Morris-ism could be termed music visualization, when he has dancers imitate gestures that match the lyrics. It’s like he’s checking to see if we’re listening and watching enough to get his little “Easter eggs.” When the lyrics proclaim: “There are mountains and hillsides enough to climb,” in pairs, one dancer falls as another lifts an arm up — creating the base and peak of the mountain. Later, accompanying “There are sunbeams and moonbeams enough to shine,” one dancer pushes an arm upward with a one-footed hop on sun, the second follows in the other direction on moon as a raised arm indicates a moonbeam.

Next, to “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” on the phrase “What do you get when you kiss a guy? You get enough germs to catch pneumonia,” a little chase ensues before one dancer forces a sneeze on cue at pneumonia. Again and again, Morris has the dancers mimic the lyrics in ways that are easy, obvious, and cute. In my college choreography class this “Mickey Mousing” the music was denigrated as too simplistic. I think it’s become an easy go-to for Morris; it makes the audience feel that they “get” modern dance while letting them feel “smart.”

Morris is at his best at inventing and reshuffling dancers in evolving floor patterns here. With ten dancers moving in, shifting into duos and trios, or playing a soloist against the group his amiable locomotor walks, runs, skips, skitters, and leaps shuffle and reshuffle the landscape on stage. And all this patterning mostly jives with Bacharach’s jazzy, subtle syncopations that add interest to his standard 4/4 common time musicality.

In Harriell’s churchy rendition of “Don’t Make Me Over,” dancers flop and tumble, trying for quirky opposition, then punch a fist in the air. For “Always Something There to Remind Me,” the gesture of choice is pulling on, off, or straightening clothes, as if miming changing an outfit is enough to forget an old lover. For lovers, lost, found, wanted, and wanting are what Bacharach’s lyricist pens so adeptly.

One oddity, “The Blob,” features a dissonant clatter of horns, drums, and piano as the dancers clump together in a pile-up of chairs and limbs against Nicole Pearce’s eerie, blood-red lighting on the backdrop. At first, I thought this creepy start would morph into “What’s New Pussycat?” But, no, a quick Google search told me Bacharach actually composed the film music, and theme song, for the 1958 film The Blob. And that’s what happened: they created a blob of bodies and chairs before moving on.

The evening song cycle concluded with “I Say a Little Prayer,” and here Morris brought the company full circle, returning dancers to the opening circle, as they intersect in a bit of a basket weave. Some now-expected goofy movements — dancers’ arms flapping like wings of graceless angels, as they parse out a pony-like bounce — garner a laugh or two. Then a lexicon of the gestural motifs is recapitulated as the company, two-by-two, one-by-one, makes their way off stage, leaving a lone dancer to exit. The Look of Love ends not on a high note, a bright note, or even a grace note, but on a breathy “Amen.” It’s like a sigh — of relief, of longing, of completion, perhaps. But it feels inadequate, even incomplete.

Throughout, the dancers adeptly work through Morris’ signature paces, but for the most part, they don’t project any particular deep feeling to the movement, the music, or even one another. Sometimes they were just going through their paces rather than reveling in the music visualizations. It’s as if they’re still looking — for inspiration, for ways to fully love and embrace this new work. And it’s a shame because the musicianship of the ensemble should draw these dancers in, but they haven’t fully committed themselves to loving The Look of Love.

This review originally appeared on DC Theater Arts on October 29, 2022, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2022 Lisa Traiger

Spotlighting Ballet Excellence

Reframing the Narrative

Dance Theatre of Harlem, Ballethnic Dance Company, and Collage Dance Collective

John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Opera House

Washington, D.C.

June 14 – 19, 2022

By Lisa Traiger

Ballet has had a white supremacy problem since the earliest steps were codified in the court of Louis XIV. Once a way to broadcast power, wealth, and proximity to the French king, over the years, the dances once practiced and performed by courtiers evolved into a professionalized artform that emulated the strictures and hierarchical structures of the European court system. More than four centuries later, ballet remains an elite and, in many cases, predominantly white artform.

Predominantly Black ballet companies have been few over the past century — among them was one homegrown right here in Washington, the Capitol Ballet Company, founded by the formidable Doris Jones and Claire Haywood of the Jones-Haywood School of dance, which still teaches new generations of primarily African American ballet students in its Georgia Avenue NW studio. On the heels of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s assassination, a New York City Ballet star and George Balanchine’s first Black male principal dancer named Arthur Mitchell founded the now-venerable Dance Theatre of Harlem, today directed by native Washingtonian and former DTH ballerina Virginia Johnson.

But Black ballet dancers are not unicorns. And that was exactly what two mixed-bill ballet programs in the Kennedy Center’s Opera House, plus additional panels, master classes, and ancillary events comprising Reframing the Narrative, intended to demonstrate. The opening night performance began with a narrator invoking the spirit of Sankofa, from Ghana’s Twi language, meaning to look back while moving forward, as a way to honor past “unicorns” — Black ballet dancers whose successes have not always been recognized and lauded in equal measure as their white counterparts’.

Following, a simple screen featured a roll call of dancers collected by a one-time Dance Theatre of Harlem dancer, Theresa Ruth Howard’s Memoirs of Blacks in Ballet, an archival project to gather the evidence that Black bodies matter in ballet and must be neither ignored nor forgotten. The scrolling list of 624 names on opening night, just four nights later on Friday, June 17, had grown to 650 names.

Reframing the Narrative is meant to illuminate Black excellence in the ballet world, co-curator Denise Saunders Thompson, president and CEO of the International Association of Black in Dance, stated in an address to the audience during the program. She was joined on stage by co-curator Howard, who worked on a Kennedy Center–commissioned work meant to showcase Black ballet voices from the selected choreographers to the dancers who were invited from high-level ballet companies from around the world to participate. Howard then offered the audience a question to ponder in this historic coming-of-age moment for the ballet world: “What does reframing mean for you?” She noted that it is set forth as both a provocation and invitation, but it is also intentionally a gift “to ourselves and to you,” the audience.

The two distinct programs featured three ballet companies that center Black and Brown dancers, choreographers, and artistic directors — Dance Theatre of Harlem, Atlanta’s Ballethnic Dance Company, and Memphis’s Collage Dance Collective, along with the world premiere commission by Seattle’s Donald Byrd featuring 11 dancers.

“From Other Suns” was created by Byrd during a two-week Kennedy Center residency at the REACH this month. Based on The Warmth of Other Suns, Isabel Wilkerson’s 2010 account of the Great Migration, it reflects on Black Americans who moved from the South up North, to the Midwest and the West starting in the early 20th century. This migratory shift changed the nation, as Wilkerson asserted. In “From Other Suns,” set to a score by Kennedy Center resident composer Carlos Simon, the work is a meditation on movement — migration, if you will — from the opening when a single man walks on stage to the evolving groups, trios, and pairs that interweave dancers in linked chains, swirling vortexes, and, ultimately, a line traveling single file across the diagonal and off stage. Byrd, a modern dance choreographer, has an affinity for the clear precision and lines of ballet, but he is not wedded to classicism. Rather he draws on ballet’s codified vocabulary yet makes it his own, allowing dancers freedom in their torsos, hips, and arms before they reconnect with their centers. In intricate coupled moments, pretzel-like lifts support women in difficult balances, while dancers find the floor, even flat on their backs, their point up in the air.

If Byrd has a narrative for “From Other Suns,” it is not evident or necessary. Instead, the evolving structure of groups moving en masse, or individuals or couples breaking away, lends a migratory sensibility to the piece, and, with Pamela Hobson’s saturated, shadowy lights and the black practice wear of leotard and tights for costumes, the work resonates with a somber tone. In a nod to mid-20th-century neoclassicism, a few Balanchinisms glimmer forth, but in no way make a statement or pay homage to America’s most prominent ballet choreographer. Instead, these glimpses are simply an acknowledgment that this 21st-century American ballet draws from many roots; others include simple vernacular and pedestrian moments tucked into and between multiple pirouettes or splicing split leaps.

With DTH’s long history as a regular visitor to the Kennedy Center, particularly in the 1980s and ’90s, and later offering yearly pre-professional summer ballet training for aspiring dancers, the Reframing week opened with the company’s “Balamouk,” a bright, jazzy and folkish romp by Belgian-born, Amsterdam-based Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, which allowed the company to display its personality and aplomb. The troupe, known for its classical and neoclassical chops, also shared the “Odalisques” variation for the classical work Le Corsaire, a study in sturdy balances, turns, and pointe work performed by Amanda Smith, Alexandra Hutchison, and Ingrid Silva.

Opening the second program on Friday night, DTH gave a nod to its lineage with resident choreographer Robert Garland’s “Gloria,” featuring Francis Poulenc’s setting of part of the Catholic mass. The curtain opened to reveal a septet of girls, smiling and displaying their youthful port de bras — coordination of the arms. Garland draws frequently from street and club dances, facilely rebranding them into the ballet vernacular. “Gloria” hints at that on occasion, with quirky elbows and folksy grapevine steps, but the piece emulates both a bright reverence and a spiritual force, particularly when one woman is borne overhead in a cross position.

On Tuesday’s opening-night program, Ballethnic Dance Company also brought a spiritually based work. “Sanctity,” choreographed by company co-director Waverly Lucas, with a live percussion and jazz score by L. Gerard Reid, draws on African roots evident in the score and in the physicality. Each dancer contributed both poetic statements, which were voiced over (although hard to hear over the live drumming), and talisman-like objects. These were carried on and placed at an altar-like structure while the performers, clad in white, danced. The cultural connections to root African forms and structures remained evident even with the balletically based point work in the foreground. On Friday, the company brought excerpts from its full-length “The Leopard Tale,” an entertaining and imaginative trip to the African jungle and plain featuring undulating snake-like creatures, and a playful and predatory pair of leopards. This audience pleaser featured plenty of splits, high kicks, and acrobatic tricks along the adventure.

Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Koko Taylor, and Bobby “Blue” Bland put the Collage Dance Collective artists in a bluesy mood. To the tremor and twang of slide guitar, “Bluff City Blues,” a jazzy and hip take on the blues, features its earthy moments from choreographer Amy Hall Garner, but sometimes even with the fan kicks, hip switches, and rolls, it gets a bit staid, and the men’s blue polo shirts don’t feel quite right. But the company does a great job at getting the audience to clap along — a feat in a ballet-focused program.

Collage topped off the Friday evening program with its new production of “Firebird,” featuring the famed Igor Stravinsky score. The Canadian-trained founding artistic director Kevin Thomas choreographed this fairy tale of a prince — Ricky Flagg II on Friday — seeking his soulmate who runs into an enchanted firebird — Chrystyn Fentroy — in the forest who gifts him with a magical feather. The cast is rounded out by Precious Adams of English National Ballet as the Princess of Unreal Beauty and various wizards, maidens, and monsters. The colorful ballet had scenery by Alexander Woodward and costumes by Gabriela Moros Diaz. Originally a 1910 Ballet Russes piece, this 2021 version retains the ballet’s plot and vision and reflects a contemporary attitude in the performances.

Reframing the Narrative’s co-curator Saunders Thompson shared with the audience that in visioning these programs she wanted to create a “blackout.” In high-school pep rally parlance, that means one team’s fans wear all black to a nighttime game. But here, at the Kennedy Center Opera House and rehearsal studios for a fortnight in June, this blackout was far more significant. Representation on stage was a given, but Thompson went further, ensuring the orchestra conductors, stage managers, lighting designers, and others working behind the scenes were also Black or Brown-identifying artists. Ballet for centuries has been a white artform, from its tutus and tights to its choreographers and dancers. Reframing the Narrative is another step in forging a path forward toward re-visioning ballet into a more equitable and representative art form for all people.

This review originally appeared on DC Theater Arts on June 22, 2022, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2022 Lisa Traiger

leave a comment