New Season: New Hope?

District Choreographer’s Dance Festival

Dance Place, presented at Edgewood Arts Center, Brookland Arts Space Lofts Studio, Dance Place Arts Park, Dance Place roof, offices, and Cafritz Foundation Theater

Choreography: Kyoko Fujimoto, Dache Green, Claire Alrich, Shannon Quinn of ReVision Dance Company, Gerson Lanza, Malik Burnett, and Colette Krogol, and Matt Reeves of Orange Grove Dance.

Washington, D.C.

September 9 – 10, 2023

When Dance Place opened its season each September, it heralded a surfeit of dance performances for the next 11 months. In fact, the nationally known presenter for decades offered up live dance performances across genres from modern to African forms, tap, bharata natyam (a classical Indian form), hip hop, flamenco, performance art, post-modern, raks sharki (belly dance), salsa rueda, stepping, even contemporary ballet, to mention just a few. Dance lovers could be assured of a show nearly every weekend of the year from September through June, with a smattering of performance options spread across the summer. Most years during its heyday, Dance Place presented between 35 and 45 weeks of dance annually, from both regional companies and national and international artists. Among those were first D.C. performances (pre–Kennedy Center invitations) from David Parsons Dance, Urban Bush Women, Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, Rennie Harris/Puremovement, Blue Man Group, and dozens of others. And along with well-curated programming, the organization offered professional and recreational studio classes in modern dance, West African dance and other forms, and a free summer arts camp for neighborhood children.

The feat, presenting more dance annually than the Kennedy Center, happened under the indefatigable visionary leadership of founding director Carla Perlo and her co-director Deborah Riley. Since they stepped away from leadership in 2017, the nationally renowned organization has struggled to find its new identity under two different artistic directors, an acting director, a global pandemic, and presently little institutional knowledge regarding the organization’s outsized influence in the dance world.

But season openings always offer a fresh opportunity to hope.

The 2023/24 season marks Dance Place’s 44th year. September 9 and 10, the organization chose to continue a tradition of showcasing locally based artists in new and recent works, which dates back to the Perlo and Riley era, and “post-pandemic” Christopher K. Morgan named the season opener the District Choreographer’s Dance Festival. This year, Dance Place and seven choreographic artists showcased not only their works but also the studio, performance, and space assets the organization manages and has access to along 8th Street NE, hard by the Metro and railroad tracks, just a short walk from Catholic University.

The afternoon began at Edgewood Arts Center, a community room used for weddings, parties, classes, and the like. Choreographer Kyoko Fujimoto, who also holds a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, fashioned a contemporary ballet quartet featuring point work and lifts, punctuated by the angularity of 90-degree elbows and knees — perhaps an ever-so-slight nod to Balanchine’s mid-20th-century neo-classicism. The work, “into the fields,” was meant to recall the experience of a medical MRI. That was evident in the horizontal crossings of single dancers rising and falling like pointed peaks and valleys of a heart monitor readout. It could also be heard in Caroline Shaw’s music from “Plan & Elevation” and another musical sequence from V. Andrew Stenger and Fujimoto. The stark black biker shorts and white tops provided an ascetic look for dancers Sara Bradna, Ian Edwards, Max Maisey, and Sophia Sheahan.

The audience was then led down the street to a Brookland Arts Space Loft studio for performer/choreographer Dache Green’s “Evolution(ary).” In the tight, bare studio, Green, long, lean and powerful, struts forward in chunky black heels, jean shorts, and an olive green trench coat. Viola Davis’ resonant voice is heard in her famous 2018 speech for Glamour magazine: “I’m not perfect. Sometimes I don’t feel pretty. Sometimes I don’t want to slay dragons … the dragon I’m slaying is myself …” To that, and then to a Beyonce-heavy score — “I’m That Girl,” “Church Girl,” “Thick,” “All Up in Your Mind,” peppered with other artists like Kentheman, Inayah Lamis, and Annie Lennox and the Eurhythmics — Green grabs center stage like a model on a catwalk, owning the space and moment as he poses, struts, bumps and grinds, vogues and twerks, all the while lip-syncing. It’s a public and private confessional about discovering and owning one’s personal story with power and self-love, acceptance, and being fierce.

Back outside in the partly cloudy afternoon, if one didn’t look up, you’d miss ReVision Dance Company’s Amber Lucia Chabus and Chloe Conway, clad neck to ankle to fingertips in highlighter pink and highlighter green respectively, poking a jazz hand, leg, or foot out from the Dance Place Roof. Choreographer Shannon Quinn let her two dancers loose on the roof to play with each other and with the viewers two stories below. I recalled film and photos of choreographer Trisha Brown’s 1971 “Roof Piece” and loved this nameless piece d’occasion all the more for its nod to post-modern dance history, while not taking itself too seriously, including playful moments and silly mime as the duo stepped down to disappear, then pop up seconds later in another location.

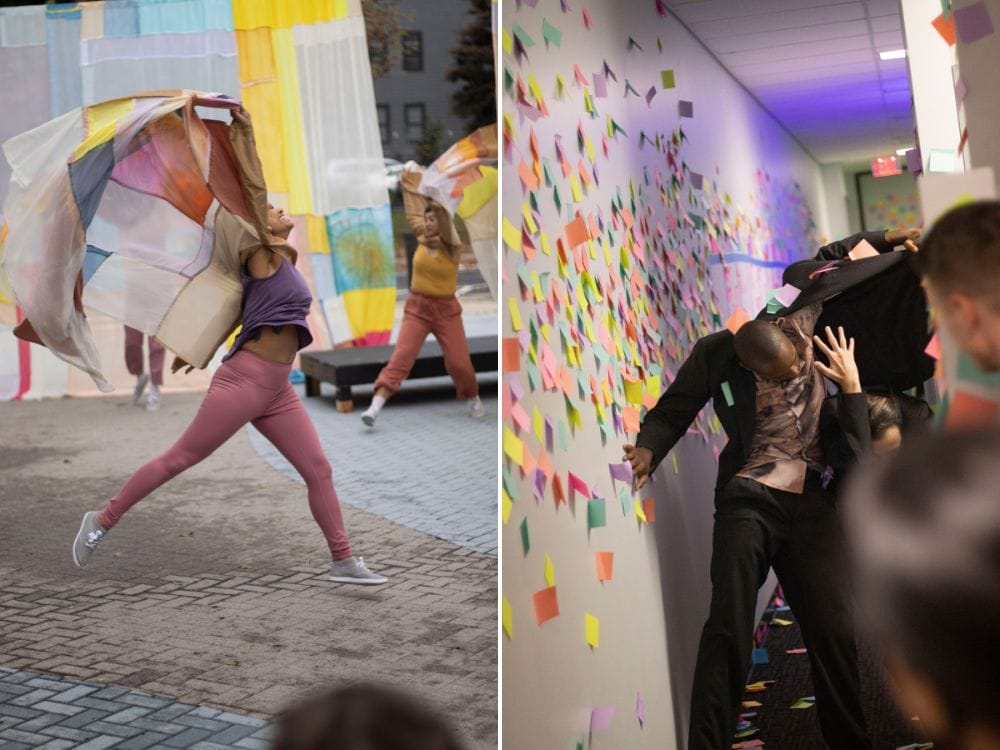

Claire Alrich’s “scenes from an elevator ascending” spread out on the Arts Park, a former city easement of land Perlo developed into a multi-use space for the community to congregate between Brookland Arts Lofts and Dance Place. With a set of stitched-together curtain-like panels and flowing cape-like tunics in mauve, mustard, and cantaloupe colors designed by Alrich and Mara Menahan, the three dancers stretch their arms to work the expanse of the costume. The work feels like an organic transformation in process. I was reminded of the caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly cycle, particularly as the dancers gently left the space walking away down Kearny Street as Santiago Quintana’s score faded.

“Paper Jungle” was meant to be a ten-minute experiential piece for ten people at a time to walk through the upstairs office cubicles of Dance Place. Technical delays kept groups waiting, but Orange Grove Dance, helmed by choreographic and design partners Colette Krogol and Matt Reeves, is consistently worth a wait. Entering the tightly constricted hallway, walls scattered with Post-it notes, “Paper Jungle” featured dancers Robert Rubama and London Brison joined by Reeves, who at times carried an open laptop on record. Audiences waiting in the downstairs lobby could watch — spy — on happenings upstairs on the large multi-picture video screen. Three men clad in slim black suits unfurled muscular, manic motion exploding along the cubicle corridor with bursts as legs and arms flung akimbo. The pressure cooker feeling of too much paper, too much movement, too many people, and sounds in the constrained space felt like a bad day at the office. Musicians Daniel Frankhuizen on cello and synthesizer and Jo Palmer on percussion compounded the atmosphere. “Paper Jungle” resonates with the overstimulated workloads and life loads so many carry, but, even so, with so much to see in such a short time span, it was hard to depart.

After a break the evening included two solos in the Dance Place Theater: percussive tap dancer Gerson Lanza’s “La Migra” explored his Honduran roots and emigration journey, while Malik Burnett’s “In Here Is Where We’ll Dwell” tackled his personal spiritual journey. Both works were personal testimonies to triumph over adversity. Lanza built on ancestral connections to traditional Africanist footwork in bare feet on an amplified wood tap board, pounding out syncopated bass and treble notes before donning brown leather tap boots for a soliloquy in sound. Burnett entered from the lobby hooded — a monk’s robe or a hoodie, in the half-darkness it’s both. Video clips draw on celebrated inspirational personalities from Oprah Winfrey to Amanda Gorman, Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, while the dancer draws himself out to expansive reaches highlighting a spiritual sense of striving for redemption. The work concludes with a slow walk upstairs through the audience to a fading light.

The festival format program, which began at 4:00 p.m., ran through about 5:30 p.m. with a break before the final two works went up in the theater, finishing up shortly after 8:00 p.m. For dance adventurers and dance lovers, this was full immersion; others may not have been so satisfied.

Finally, while this District Choreographer’s Dance Festival heralds a new season, Dance Place’s programming remains truncated. Some months contain just a single run and later in the season multiple weeks are booked, with most presentations being for a single performance rather than a two-show weekend. The organization suffered multiple blows with the retirements of its founding leadership, and turnover in its replacements, along with the ongoing challenges of the pandemic and post-pandemic recovery. Six years along, Dance Place is still finding its footing. It may never be the same. We can only hope the new leadership team remains committed to building on past successes and supporting dance and dancers for generations to come.

This review originally appeared September 13, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Romp and Rumination

Choreographer Sarah Beth Oppenheim scales a moving and storage warehouse

‘Many Extra Only More’

Heart Stück Bernie

Extra Space Storage, 2800 8th Street NE

presented by Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

July 7-8, 2023

By Lisa Traiger

It’s been a while — a long while — since I saw a locally produced, original choreographic work that wowed me. Saturday night July 8, 2023, I was wowed. As I sat on the Franklin Street NE bridge pedestrian walkway, facing the rectangular industrial Extra Space Storage building on 8th Street, waiting for the sun to set, I donned “silent disco” headphones and bobbed my head to the beat. The music, edited by Oliver Mertz, ranged from Bela Bartok to Ethiopian musician Mulatu Astatke to pop band Animal Collective and Ukrainian group DakhaBrakha to name a few of the eclectic choices. Traffic whizzed by on the bridge, leftover illegal fireworks boomed in the distance, a siren screamed, and on railroad tracks parallel to 8th Street, trains rumbled by.

As the sky darkened, the 20 windows of Extra Space Storage brightened, then music pumping, at once 40 dancers filled the 4 x 5 grid of windows, bopping in brightly colored separates of red, yellow, and orange. Many Extra Only More unfurled as a massive and wow-inducing site-specific piece from the marvelously imaginative and generative mind of Silver Spring–based choreographer Sarah Beth Oppenheim, who leads ten fearless dancers of her company Heart Stück Bernie. Many Extra Only More begins like a romp. You can’t help but smile and wish you were up there dancing with them.

But there they are, each in a separate window box, brightly lit, smiling. Together and alone. And soon the primary colors and vivid playfulness, quirky, tick-like gestures and poses, take on moodier shadings. It’s not so long ago, as memory serves, we were all living in and in front of computer-lit boxes, isolated in our homes but distantly together in our Zoom rooms at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Oppenheim’s choreography does those quick tone shifts often, and well. She’ll make a ridiculously cute set out of cardboard cut-out shapes — oversized paper-doll dresses, puffy armchairs, yellow suns and crescent moons, rainbows and stars — or reams of paper with childlike drawings or PowerPoint-like instructions for the audience. She crafts as if Martha Stewart taught kindergarten and her dances emote an unspoken language filled with silent action verbs; dancers skip and hop, slink and saunter, shimmy and slither, ooze and vibrate, twitch and punch, bounce and breathe. Oppenheim has some of the quirky bright cheerfulness along with the millennial zeitgeist of sitcom actress and musician Zooey Deschanel that belie her own bright smile and vivid thrift store wardrobe.

Oppenheim has been an artist-in-residence at Dance Place — the producer of this outsized, and outside, evening — and has presented work on its stage. Her choreography has also been seen in gardens and galleries — including the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing — alleyways and storage closets. She sees dance in life’s most ordinary moments and elevates those mundanities with movement and visions of how living and dancing deeply intertwine. Her work in the community with its light and dark tones and its serious fun is her way of spreading the gospel of creative thinking to the masses.

Saturday night Many Extra Only More addressed multiple ideas in its 50 fast-moving minutes. Audiences had to come to terms with the caveat that they wouldn’t see everything. A pre-show announcement noted that no spot would allow viewers to see it all completely, and they were welcome to move around throughout the show. Sitting on what I believed were prime “balcony seats” on the Franklin Street NE bridge made me wish I was below, across the street at the Dewdrop Inn looking head-on at the dancers filling the windows. But I was quickly reminded of Merce Cunningham’s Events where dancers populated public spaces and you couldn’t catch it all, intentionally. Oppenheim’s work also nodded to another mid-20th-century modern dance choreographer, Anna Sokolow, whose acclaimed Rooms explored the isolation individuals felt in their massive apartment buildings: living in tight clusters, but each alone in their singular rooms. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades — found objects displayed as art — also came to mind with the readymade non-theatrical setting and set pieces — ordinary stuff you would find in a storage unit. Or maybe that’s a nod to the hit show Storage Wars. No matter, Oppenheim knows what she’s doing at every moment of this large-scale romp and rumination.

Many Extra Only More spooled out episodically in those window frames, vertically, horizontally, diagonally, and randomly. Oppenheim — with rehearsal assistance from Nancy Bannon and Kourtney Ginn — realized a choreographic feat in spatial organization navigating the windows like a Rubik’s cube master. Dancers shifted in groups, individuals, sometimes carrying in props, crafty cutouts, even at one point a striped sofa. Lighting by Kelly Colburn and Mark Costello used colored gels on the intense fluorescent warehouse lights, among other large-scale tricks, to shift mood and tone during the vignette-like sequences.

Moments of group synchronicity — even as dancers eschewed complete unison — conveyed celebration; a series of folk-dance–like chains and circles reminded me of a wedding or bar mitzvah. Then smaller configurations of two, three, or five reflected relational and interactive conversational moments. One dancer — Sadie Leigh — donned a green striped robe — like the green garage-like doors of the storage units — on which a collection of paper cutouts of overflow detritus were pinned: a lamp, a chair, an end table, a candlestick. Metaphorically, the choreographic structure with this oversized cast reflects the overstuffed lives so many Americans live today — homes filled with too many dishes, toys, books, sofas, and lamps, and not enough Marie Kondo self-reflection to discard what isn’t joyful. Instead, those excesses of our lives, which we can’t let go of, become a boon for the storage industry. And a reflection of the baggage we hang on to.

This is seen in moodier sections of confrontation, dancers battling as we watch — becoming voyeurs looking in from the outside. A song comes on with a violent thread as slow-motion fists and clawed hands are drawn out. A woman is splayed across a table — others manipulate her. Across the way, two dancers run themselves into the windows, again and again. Suddenly, nothing is bright or fun, sunny or sweet. Cute sun and rainbow cutouts taped to windows can’t whitewash the discord and pain surfacing in this glass-housed world Oppenheim has wrought.

The mood modulates — like life — in shifting vignettes. We follow the dance modulate from joy to pain, playfulness to violence, happiness to despair — and, finally, at the end, back to another dance-off, each dancer in her window grooving to the beat, then departing a few at a time, only to reappear on the street in front of the warehouse. The earphones still blasting music, the disco still silent, but then everyone has clumped together, and some audience members join the group. If Oppenheim wished for a big, bold, extra, supersized statement piece about the simple yet profound ways dance affects us, changes us, makes us think, moves us, and makes us move, she did it.

In recent years, we’ve seen some tectonic shifts in dance in Washington, D.C., from the departure of MacArthur “genius” grantee Liz Lerman a dozen years ago, to the retirements of Dance Place co-directors Carla Perlo and Deborah Riley in 2017, to the departure of Septime Webre from the Washington Ballet that same year, and the recent untimely losses of Michele Ava, cofounder of Joy of Motion, and Melvin Deal, founder of African Heritage Dancers and Drummers. Just this year, the service organization Dance Metro D.C. closed down. Dance in the region has been on unsteady footing. Even before the pandemic shut down studios and companies for months and months, including some that didn’t survive, we were seeing fewer dance presentations in smaller venues beyond the Kennedy Center’s large stages. Dance Place’s once-weekly performance presentations have diminished to one to two performances a month.

This, Oppenheim’s largest and most complex work to date, was initially conceived in 2017, but delayed by that global pandemic. The complexities of the large working business site, technical requirements, and a massive cast for a locally produced dance company demonstrate that creative forces continue to percolate in D.C.’s homegrown dance community.

So Many Extra Only More bodes well for the future. Let’s hope Dance Place and the D.C. metropolitan dance community can take inspiration from Oppenheim’s extra-large, many-dancer production that shouts “More” with its collection of a strong cadre of young and veteran dancer/choreographer/creatives in its cast.

Featuring Heart Stück Bernie Dancers

Emily Ames, AK Blythe, Amber Lucia Chabus, Terra Cymek, Kate Folsom, Raeanna “Rae” Grey, Sadie Leigh, Patricia Mullaney-Loss, Nicole Sneed, Kristen Yeung

with

Claire Alrich, Katherine Berman, Lauren Bomgardner, Lauren Brown, Jennifer Cinicola, Sarah Coady, Annika Dodrill, Allison Grant, Safi Harriott, Jocelyn Hartman, Faryn Kelly, Betsy Loikow, Julia McWest, Bretton Mork, Simone Nasry, Annie Peterson, Sarah Raker, Jane Raleigh, Alison Waldman, Berea Whitley

and

Elizabeth Barton, Jadyn Brick, Annie Choudhury, Lauren DeVera, Celina Jaffe, Emilia Kawashima, Luisa Lynch, Chitra Subramanian, Zoe Wampler, and Janae Witcher

This review originally appeared July 10, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Holding

And Now, Hold Me

Directed and choreographed by Britta Joy Peterson,

with performance and movement collaboration by Sergio Guerra Abril and Dylan Lambert

Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

January 22-23, 2022

By Lisa Traiger

Choreographer and ardent collaborator Britta Joy Peterson has been creating dance, video, and performance pieces in the Washington, DC, region since 2016, when she took a position as a professorial lecturer at American University in the District.

Her newest piece, And Now, Hold Me, is part of a trilogy Peterson began work on in 2014 or ’15, she said after Saturday evening’s program at Dance Place. Each work — including “Vinegar Spirit,” which came to Dance Place in January 2019 — wrestles with time and space in intentional ways to tease out philosophical and phenomenological concepts in a kinetic palette. What’s most interesting about this triptych of pieces is Peterson’s keen focus on space and how the introduction of bodies moving through it changes, literally, everything — the architecture, the meaning, the temperature, the feeling, even the air in the room reshapes itself. For And Now, Hold Me, a duet, the space designed by Elsa Rinde creates a stage within a stage demarcated by white PVC pipes slanted like a giant soccer goal framing the performers, with a white floor floating in the larger surrounding black void.

Two men, sharply dressed in wool coats, neat sweaters, slacks, and shoes, sit cross-legged on the floor looking like schoolboys awaiting roll call. “In the beginning … and now,” one intones. Then a monologue spoken in succession by both men, but not to one another, pours forth, in poetically Biblical cadences about flesh and how it’s in and of the world, the stuff of life, it provides a way of perceiving and making meaning. “Through flesh,” one says, “I know you.” Still seated, they twist, bend, windshield-wiper their knees, gesture in perfectly intricate unison and a low thrum of sound crescendos. Like twin brothers they rise and begin to disrobe. A shift in Evan Anderson’s lights transforms the backdrop, which appeared as colorful and white vertical blinds, into a loosely woven web of multicolored ribbon, which streams from a giant spool at the side of the stage. Dancer Dylan Lambert behind stage pulls ribbon from the endless spool and adds to the spidery tapestry.

Meanwhile, with slippery grace, Sergio Guerra Abril meanders between gestural brushes of his hair and loosely articulate twists, tumbles, balances that unwind and rewind, a manifestation of the unspooling ribbon. What becomes a series of episodes, silent playlets in a sense, is broken up by canned applause, when each performer pauses for an unironic bow. Guerra Abril dons a shimmery blouse, red go-go books, and a flouncy white skirt for a playful lipsync of “Desatame” by Monica Naranjo. His playful drag and voguing offer up a fantastic death drop — a split-second fall to the back, one leg sexily raised in the air.

Lambert then has his own bit of fun impersonation. Introduced by a few bars from Van Halen’s “Jump,” he enters with towel and yoga mat, converses with imagined gym rats about exercise, bitcoin, and dogecoin, all in perfect yoga-bro fashion.

An improvisational duet on expected feminine and masculine tropes allows the dancers to tweak social and cultural expectations of the alpha male and bitchy female. Guerra Abril reads from a series of shlocky blog posts that advise that men should “take up more space to look more powerful” while women should “avoid pain at all costs.” All the while they tumble, lift, balance one another on a hip or shoulder in an easygoing improvisation. On either side, sign language interpreters make this and all the spoken word accessible.

As the work winds down, strains of Liszt’s dreamy “Liebestraum No. 3” build, shifting the demeanor of the space that has contained so many moments of bodies moving and filling the void, light painting over the darkness, architecture delineating the blank stage canvas. The two men begin packing up the clothing and props; the woven spidery tapestry, their own words and phrases, parsed out over the course of nearly an hour have reached a quiet moment of intimacy. “And, now … the end” arrives, but, still, they’re not finished. There’s one more thing to do.

They stand and, finally, hug, body to body, flesh to flesh. Two become one. Space and time have contracted and exploded. While And Now, Hold Me is absolutely not a “pandemic piece,” this moment of coming together resonated in a world where many people have not hugged or been hugged for nearly two years now as the ongoing challenges of isolation and quarantine continue to hold some hostage to COVID-19 and its variants. Peterson’s work meditates on time and space, with moments of moving beauty, irony, fun, and, finally, a thoughtful confluence of bodies and flesh. I’ve avoided writing on her work until now because I hadn’t found enough in it that appealed to me. In And Now, Hold Me, I discovered much that spoke to me, particularly through the exquisite performances of Abril and Lambert, as well as the finely conceived structure and expert production of Peterson’s artistic and advisory team. I’m glad I returned to her work to discover a deeply conceptual study of what it means to move and take up space. A solo dancer on stage evokes an individual’s world, but Peterson shows us that two people sharing space create a universe of possibilities.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts on January 24, 2022, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2022 Lisa Traiger

Woke

Wake Up!

MK Abadoo and Vaughn Ryan Midder

Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

May 5-6, 2018

By Lisa Traiger

Walking into the back door at Dance Place this past weekend, felt akin to entering a nightclub, albeit a friendly one. After getting the backs of our hands stamped, we walk onto the stage, which has been transformed into a dance floor; some folks choose to groove a bit, others take seats at the periphery of the circle. The occasion, a remount of choreographic activist MK Abadoo’s Wake Up! begins as a party, but by the time the hour is up, no one is laughing.

Abadoo, currently a guest artist at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, drew inspiration from Spike Lee’s 1988 social commentary on being young, gifted and black, School Daze. While the movie is also a romp into the social mores of fraternity and sorority members at a fictitious HBCU, Abadoo, an alum of Liz Lerman Dance Exchange, flips Lee’s premise on its head. Instead she probes how present-day black students navigate the minefields of race, class, social and political structures of a PWI — predominantly white institution.

Abadoo’s six performers — Moriamo Temidayo Akibu, Kevin Carroll, Shanice Mason,Tariq O’Meally, Selyse and Asia Wyatt — clad in their fictional campus t-shirts that proclaim “priviridge west institute,” navigate through vignettes that lay bare the continuing effects of institutional racism and segregation on young men and women of color. While dance is elemental — the dancers toggle through club moves, hip hop, swing, jazz and blues — they also nod to Lee’s references to minstrelsy and African dance roots.

A homecoming contest turns into a lesson on “good and bad” hair — the beauty shop battle song from the Lee film — pits darker skinned women with natural locks and braids against lighter skinned women with more “desirable” hair. That is until a white woman with long straight red hair struts away the winner. The choreographer has dealt with issues surrounding black hair before, including in Locs/you can play in the sun, a work that included a 25-foot swath of hair that became both burden and amulet for black women.

Then in an imagined juke joint, Abadoo sets up a “living museum” putting her dancers on display as the “Talented Tenth.” They pose, plastered grins beneath blank eyes, and writhe under hot white spotlights suggesting, as Lee, too, did, ignominious minstrel shows in the obsequious stances — head cocked to the side, foot flexed forward like a “Steppin’ Fetchit.” Here and elsewhere throughout the evening, audience members are invited to walk through the stage space, gazing at these dancers as specimens. The horrifying realization that this is no display of talent, but a hearkening back to slave auctions — some of which took place just 12 miles away in Alexandria, Va. — causes a sense of frisson.

Abadoo’s collaborators, writers Vaughn Ryan Midder, Jordan Ealey and Leticia Ridley, have crafted a taut and searing script that is as much a pointed commentary as it is poetic accompaniment to the movement, which draws from vernacular club styles, a touch of showy jazz, hip hop and Africanist root forms. They don’t ignore history, rather they rely on the awareness — “woke-ness” — of the audience members to get their references to 3/5 a man, Martin, Brown, even Wakanda. The dancers are as adept with this mash up of genres as they are at spoken word. Also notable: the seamless ease that the audience is invited into the performing space and then smoothly ushered off.

DJ Miss Jessica Denson spins old school grooves and hotter new tracks for the dancers who find freedom and release even amid tension-filled moments. Early on four dancers run headlong into the back cinder block wall, again and again. The moment feels both frenzied and entirely acceptable: why wouldn’t these brown bodied dancers feel frustrated enough to slam themselves into a brick wall. The metaphor of living under the white gaze — under centuries of oppression — has been transformed: bodies slamming into bricks.

Yet, amid the harsh images and resonant history, these dancers too share joy, camaraderie and a sense of communal stake in their free form dancing. These four women and six men are unapologetically comfortable inhabiting this space — a circle, consciously eschewing the divisive privilege of a traditional curtained stage. Wake Up! is a necessary public exhortation to our divided nation that the legacy of America’s original sin — slavery and colonialism — remains ever present. Abadoo is among a rising generation of socially conscious African-American choreographers — Kyle Abraham, Mark Bamuthi Joseph, Rennie Harris, Gesel Mason, Camille Brown, and the list does go on. They understand intimately that the simple act of placing a black body on stage is an unapologetic political statement in 2018. Abadoo and her compatriots are working at the intersection of art and social justice at a fraught moment when a slogan like Black Lives Matter is an urgent call to wake up and move to the right side of history.

Photo: MK Abadoo by Idris Solomon, courtesy of Dance Place

© 2018 Lisa Traiger

Published May 8, 2018

2017: Not Pretty — A Year in Dance

The year 2017 was no time for pretty in dance.

The dance that I experienced this year moved me by being meaningful, making a statement, and speaking truth to power. Thus, the choreography that excited or touched or challenged or even changed me was unsettling, thought-provoking, visceral. The influence of #Black Lives Matter, #Resist and #MeToo meant that dance needed to be consequential, now more than ever. Here’s what made me think and feel during a year when I saw less dance than usual.

Not merely the best performance I saw this year, but among the best dance works I’ve experienced in a decade or more was the double revival of Pina Bausch’s “Café Muller” and “Rite of Spring” at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Alas, the company doesn’t perform in Washington, D.C., so my experience with Bausch’s canonic works are few, but I’m grateful for the opportunity to have experienced these two masterworks. Their significance cannot be understated. In “Café Muller,” the profound gravity of the performers in that closed café, with its scintillatingly scattered chairs, doorways and walls arranged in perfect disarray is humorless, just like the dancers, who arrive with their aura of existential loneliness. The bored banality of these slip-dressed sleepwalking women, the meaningless urgency of the red-head in her clickety clackety heels and green dress, the morose body-bruising couplings, as a slip-thin woman incessantly throws herself onto her male counterpart only to be flung, dropped, and sideswiped with as much care as one might give to a sack of laundry. “Café Muller’s” fragrance, with its snippets from a Purcell score, is heavy with the perfume of existentialism and the Sartrian notion that hell is other people. The work feels like life: a study of losses, regrets, and the unrelenting banality of existence. I’m glad I saw it in middle age — Pina understood it as the decade of disappointment.

A rejoinder to this nondescript yet vivid café of no exits, is the cataclysmic clash of the sexes that imbues Bausch’s version of “The Rite of Spring” with the driving forces of primitivism that jangle the nerves, raise the heart rate, ignite loins, and remind us of our most basic animalistic instincts for creation and destruction. The infamous soil-covered stage, populated with xx men and women elemental gravity in came from the It took a trip to Brooklyn, New York, because, alas, the Pina Bausch Dance Company doesn’t perform in Washington, D.C. The double revival of Café Muller and The Rite of Spring shook my world, reminding me what the greatest dance can do to the gut and the soul.

A companion of sorts to Bausch, arrived later in the fall at the University of Maryland’s Clarice. Germaine Acogny, often identified as the Martha Graham of African modern dance, brought for just a single evening her taut and discomfiting Mon Elue Noire — “My Black Chosen One” — a singular recapitulation of “Rite of Spring” drawing, of course, from Stravinsky’s seminal score, and also dealing unapologetically with colonialism. The choreography by French dancemaker Olivier Dubois places 73-year-old Acogny, first clad in a black midriff baring bra top, into a coffin like vertical box, her head hooded by a scarf. A flame, then the sweet, musky perfume of tobacco smoke draw the viewer in before the lights come up. There she sits, smoking a pipe, eyeing the audience with suspicion. The drum beats and familiar voice of the oboe as the musical score heats up, push Acogny into a frenzy of sequential movements. The French monologue (alas, my French has faded after all these years) from African author Aime Cesaire’s 1950 “Speech on Colonialism” sounds accusatory, but it’s the embodied power Acogny puts forth — her flat, bare feet intimately grounded, her long arms flung, her pelvis at one point relentlessly pumping powers it all. As smoke fills the space, Acogny pulls up the floor of her claustrophobic stage and slaps white paint on herself, brushes it in wide swaths on this box, filled with smoke. Now wearing a white bra, her lower body hidden beneath the floor, her eyes, bore into the darkened theater. Mon Elue Noire’s bold statement of black bodies, of African women, of seizing a voice from those — white colonialists — who for centuries silenced body, voice and spirit rings forth both sobering and inspiring.

A companion of sorts to Bausch, arrived later in the fall at the University of Maryland’s Clarice. Germaine Acogny, often identified as the Martha Graham of African modern dance, brought for just a single evening her taut and discomfiting Mon Elue Noire — “My Black Chosen One” — a singular recapitulation of “Rite of Spring” drawing, of course, from Stravinsky’s seminal score, and also dealing unapologetically with colonialism. The choreography by French dancemaker Olivier Dubois places 73-year-old Acogny, first clad in a black midriff baring bra top, into a coffin like vertical box, her head hooded by a scarf. A flame, then the sweet, musky perfume of tobacco smoke draw the viewer in before the lights come up. There she sits, smoking a pipe, eyeing the audience with suspicion. The drum beats and familiar voice of the oboe as the musical score heats up, push Acogny into a frenzy of sequential movements. The French monologue (alas, my French has faded after all these years) from African author Aime Cesaire’s 1950 “Speech on Colonialism” sounds accusatory, but it’s the embodied power Acogny puts forth — her flat, bare feet intimately grounded, her long arms flung, her pelvis at one point relentlessly pumping powers it all. As smoke fills the space, Acogny pulls up the floor of her claustrophobic stage and slaps white paint on herself, brushes it in wide swaths on this box, filled with smoke. Now wearing a white bra, her lower body hidden beneath the floor, her eyes, bore into the darkened theater. Mon Elue Noire’s bold statement of black bodies, of African women, of seizing a voice from those — white colonialists — who for centuries silenced body, voice and spirit rings forth both sobering and inspiring.

I was just introduced to formerly D.C.-based choreographer/dancer MK Abadoo’s work this year and I’m intrigued. Her evening-length Octavia’s Brood at Dance Place in June, time travels, toggling between Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad and a futurist vision of the world where women of African descent reclaim their bodies and voices in an ensemble work that takes inspiration also from the writings and commentary of science fiction writer Octavia Butler. The work begins with a bantaba — a meeting or dancing ground. The audience is invited onto the stage to encircle the dancers. The women, clad in shades of brown, fall to their knees, rise only to fall again to all fours. Beauteous choral music accompanies this section. Soon they stretch arms widely reaching to the sides. A sense of mysterious spirituality fills the space, a space once more enriched by the uncompromising presence of strong, graceful black women’s bodies. Octavia’s Brood is not simply about memory. It navigates between past, present and future while celebrating the durability of black women in America – there’s a holy providence at play in the way Abadoo and her dancers draw forth elemental, earth-connected movement.

They toss their arms backwards, backs arching, leg lifting, while a conscious connection to the floor remains ever present. Later, we see these same dance artists on stage, the audience now seated, on a journey that draws them to support and uphold one another. There’s a gentle firmness in their determination and a tug and pull in the choreography, underscored by a section where the women are wrapped in yards of brown fabric, a cocoon of protection. Then as they unwind it feels like rebirth.

They toss their arms backwards, backs arching, leg lifting, while a conscious connection to the floor remains ever present. Later, we see these same dance artists on stage, the audience now seated, on a journey that draws them to support and uphold one another. There’s a gentle firmness in their determination and a tug and pull in the choreography, underscored by a section where the women are wrapped in yards of brown fabric, a cocoon of protection. Then as they unwind it feels like rebirth.

In September Abadoo premiered a program featuring “LOCS” and “youcanplayinthesun,” commissions by the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage. Dramaturg Khalid Yaya Long wrote in the program that these pieces too draw inspiration from Afro-futurist sci-fi author Butler. But they also wrestle with intracultural racism. Poet Marita Golden called it “the color complex … the belief in the superiority of light skin and European-like hair and facial features” among African Americans, and others. The six dancers clad in white fuse a modern and African dance vocabulary, but more essential to the work are the smaller gestural moments. Like when an older dancer, Judith Bauer, proudly gray haired, sits on a stool and braids and combs Abadoo’s hair. She carries a rucksack, which slows and weighs down her gait. Later we see that the bag is filled with lengths of hair, locs, suggesting the burden black women carry on whether they have “good” — straight — or “bad” — curly or kinky — hair. But that quiet moment, when Bauer tends to Abadoo’s hair — it’s a maternal act, sacred and memorable for its resonance to so many who have sat in a chair while their mother, grandmother or aunt hot combed, plaited, flattened or styled unruly hair into something not manageable but acceptable to a society that has denigrated “black hair.”

Interestingly, in ink, Camille A. Brown’s world premiere at the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in November, also features black women’s hair — a subtext in a larger work that wrestles with African American identity. The evening was made more vivid by a live jazz percussion quartet helmed by Allison Miller. Structured with compelling dance vignettes that bring African American cultural and societal mores to the fore ink speaks an oft-silenced vocabulary through bodies, gestures, postures and poses. A solo by Brown feels like a griot’s history lesson articulated with highly specific gestures that vividly reflect what could be read as “woman’s work” — dinner preparations, wringing laundry, caregiving. Later Brown gives us a different story, of two guy friends — first they’re wonder-filled kids, then they hang ten, basketball their game of choice. But, unseen, unspoken, something hardens them. Later an intimate duet shows a loving couple behind closed doors. But that love belies the challenges outside that arduous nest. In ink, Brown has completed her black identity trilogy, which included Black Girl: Linguistic Play, by consciously asserting the beauty and bounty of black bodies, souls and spirits that inform, intersect and shape our larger American culture.

Interestingly, in ink, Camille A. Brown’s world premiere at the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in November, also features black women’s hair — a subtext in a larger work that wrestles with African American identity. The evening was made more vivid by a live jazz percussion quartet helmed by Allison Miller. Structured with compelling dance vignettes that bring African American cultural and societal mores to the fore ink speaks an oft-silenced vocabulary through bodies, gestures, postures and poses. A solo by Brown feels like a griot’s history lesson articulated with highly specific gestures that vividly reflect what could be read as “woman’s work” — dinner preparations, wringing laundry, caregiving. Later Brown gives us a different story, of two guy friends — first they’re wonder-filled kids, then they hang ten, basketball their game of choice. But, unseen, unspoken, something hardens them. Later an intimate duet shows a loving couple behind closed doors. But that love belies the challenges outside that arduous nest. In ink, Brown has completed her black identity trilogy, which included Black Girl: Linguistic Play, by consciously asserting the beauty and bounty of black bodies, souls and spirits that inform, intersect and shape our larger American culture.

Other standouts for me during 2017 ranged from a new work for the Ailey company by Kyle Abraham, “Untitled America,” with its narratives of incarcerated citizens and their family members, and a simple yet powerful palette of pedestrian and gestural elements, to Lotus, a rollicking tap family reunion at the newly renovated Terrace Theater, upstairs at the Kennedy Center, that traced the home-grown percussive dance from early roots to a high-spirited finale, with plenty of meditative percussive and narrative moments in between — plus enough flashy footwork.

It was also a year of change at many Washington, D.C. dance institutions. Dance Place’s founding director, the indomitable Carla Perlo retired in the summer, along with her long-time artistic associate Deborah Riley, passing the reins to choreographer/dancer/educator Christopher K. Morgan. It’s too early to tell whether Dance Place will move in new directions, but it appears that the organization is in solid hands. Morgan continues to make his own work for his company, lending continuity to the profile of a working artist-slash-administrator-slash-artistic-director.

We also have a better sense of the direction The Washington Ballet will be moving toward under artistic director Julie Kent. It appears that predictions of a company that resembles American Ballet Theatre, where Kent spent her stage career as a principal ballerina, are coming true. Remarks that The Washington Ballet is now “ABT-South” are no longer facetious; they’re reality. Kent has brought in her colleagues Xiomara Reyes, school director, and her husband, Victor Barbee, as her associate artistic director. And her commissions, too, have been ABT-centric, from an atrocious tribute to President John F. Kennedy called “Frontier,” from her former partner Ethan Steifel to upcoming commissions by Marcelo Gomes (who recently resigned from ABT under a cloud of suspicion over sexual allegations not related to ABT). But Washington, which gets a surfeit of ballet riches with annual visits from not only ABT, but also New York City Ballet, the Mariinsky Ballet and other top ballet companies, doesn’t need an “ABT-South.” The city needs a ballet company that speaks to the needs of the District and its environs, not the international ideal of Washington. An ideal Washington ballet company would be one that nurtures ballet artistry that is unique and relevant to hometown Washington, not government Washington. Former TWB artistic director Septime Webre had one vision of a ballet company by and for Washington, D.C., and some of its works under his direction made singular statements. What the city and its dance audiences don’t need? More Giselles, Don Quixotes or Romeo and Juliets by a mid-sized troupe puffed up with student apprentices.

The region also suffered a loss in The Kennedy Center’s decision to shutter the Suzanne Farrell Ballet Company. While the company never, or rarely, in its 17 years achieved the notoriety or success one would have wished for an ensemble founded by choreographer George Balanchine’s elusive muse, the early December program hinted at missed possibilities. Her company’s farewell program, a tribute to Balanchine, was strongly danced, an aberration for a company that often looked ill-prepared and at times a bit sloppy on stage, alas hinting at missed possibilities in the loss of her directorship.

2017 was also a year where dance — particularly big name ballet companies — made the news, and not in a good way. Following in the footsteps of the #MeToo movement, well-substantiated accusations of sexual harassment and improprieties against New York City Ballet ballet master-in-chief Peter Martins, rocked the ballet world. It’s again too soon to know if systemic change can come to this male-dominated leadership model and the endemic hierarchical organization of most ballet companies; but change has been a long time coming to the ballet world where hierarchy and male power reigns supreme.

Let’s hope for a new year where that status quo will be upended as ballet companies — among other companies — strive for a more equitable, comfortable and safe creative and artistic environment. The dancers deserve it. The choreographers deserve it. The art deserves it. Let 2018 be a year of change for good.

December 31, 2017

© Lisa Traiger 2017

Erotic

Antithesis: Dance Place Practice

Gesel Mason Performance Projects

Conception and choreography by Gesel Mason

Dance Place, Washington, D.C.

January 6, 2017

By Lisa Traiger

Since one of her first independent performances in Washington, D.C., at Dance Place, dancer and choreographer Gesel Mason has been navigating the taboo and the titillating. She has put a bold face on works that wrestled with race, racism and its deep-rooted role in American history in her A Declaration of Independence: The Story of Sally Hemmings (2001), as well as her ongoing “No Boundaries” project, which gives voice to African-American choreographers in a series of commissioned and revived solos. Mason also has a biting wit: one of her signature solos, How To Watch a Modern Dance Concert or What the Hell Are They Doing On Stage? takes down the sacred cows of 20th-century modernism and post-modernism in dance, with the choreographer’s tongue firmly planted inside her cheek. And, finally, and more than for good measure, Mason has often used her own text and poetry, including the searing “No Less Black,” as accompaniment to her choreography.

On her return to Dance Place, the nation’s capital’s most popular dance performance venue, she converts the black box studio theater into a post-modern burlesque house for her evening-length inquiry into the erotic, and the exotic, of embodied female sexuality. It’s a daring endeavor for Mason, who early in career was a company member of Liz Lerman Dance Exchange until forming her own project-based troupe and production company, Gesel Mason Performance Projects. Over nearly two decades, the dancer/dancemaker has tackled the profane and provocative before in Taboos and Indiscretions (1998) and her later Women, Sex & Desire: Sometimes You Feel Like a Ho, Sometimes You Don’t (2010), when she collected the stories and movements of District-based sex workers for a piece that gave voice to often well-hidden and ignored female stories.

So it was interesting that Mason names her latest work with a less provocative and more academic title: Antithesis. Developed at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she is now an assistant professor, it continues her explorations into personal and public sexuality, the role of the female in society and, an oft unremarkable theme in much American modern dance, personal expression and self-exploration. The piece features a cast of ten, including burlesque dancers Essence Revealed, Peekaboo Pointe and Love Muwwakkil, as well as more traditionally trained modern — or as Mason refers to them, post-modern — dancers (Ching-I Chang Bigelow, John Gutierrez, Kayla Hamilton, Kate Speer and Rita Jean Kelly Burns are among the cast), with a cameo by Mason’s mom, Andrea Mason. The work, in development for nearly three years, brings together these two worlds where the female body is on display, either in the dance studio and concert stage for the modern dancers, or in the strip club and burlesque stage for the pasty-clad performers. In Mason’s purview, it’s a chaotic collision.

With a stripper pole prominently displayed before the studio mirrors, the show begins. Clad in a silky bathrobe Mason serves as emcee, introducing the audience, seated on all four sides, to the ladies. There’s Peekaboo, the taut bleached blonde with an Ultrabrite smile, in her patriotic g-string and pasties. And Love, a virtuoso of the pole, caressing, climbing and sliding on her apparatus like Simone Biles on the balance beam. But there are other more prosaic dancers, whose talent for, say, Quickbooks, savings accounts and bank account reconciliations is lauded as vigorously in Mason’s biting narrative. And on that note it becomes clear that for the next hour the audience is in store for more that so-called tits and ass. Mason has constructed a probing critique of a slice of contemporary eroticism.

Informed by poet and literary critic Audre Lorde’s essay “Uses of the Erotic,” Mason set out to understand the female body as it is seen and used, empowered and comodified, in various public spaces in the 21st century. For Lorde, the erotic isn’t eroticism, particularly not derived from the male gaze that has made women’s bodies objects to be stared at, re-shaped, manipulated, and appropriated. Lorde views the erotic as harnessing female power — that vital physical and spiritual lifeforce that imbues creativity of all kinds on individuals. Eroticism, then, is about knowing oneself truly, and it’s about embracing the chaos of life and living.

Antithesis pursues that idea by mediating between the patriarchal view of the erotic — the specific kinds and shapes of women’s bodies on display for male desire and pleasure. But instead, especially the burlesque dancers demonstrate complete comfort and confidence in their bodies. They own their eroticism, their physical power and the hold they have over the opposite sex in particular. And they revel in it. They perform their unique identities for their own pleasure; the audience is merely along for the ride. The pasties and g-strings? Sure they’re hot and sexy, as are the burlesques and strip teases. But removed from a gentleman’s club or a strip joint and located in a typical concert venue, the performative nature of the dance is transformed from eroticism into commentary on the feminine, the female, patriarchy and wholesale comodification of bodies, whether its pasties or Quickbooks.

Mason then traverses the divide between women in modern and post-modern dance and women who publicly display and sell their bodies. Is there, ultimately, a difference? Aren’t we all for sale? Is there always a price? Is one art and the other commerce or objectification?

One dancer, barefoot, clad in jeans and a lumberjack shirt, rolls on the floor, releases her weight, shifting her dynamics with limber ease, her face an expressionless mask. Then on comes Peekaboo in her stilettos and pasties. She parses through the same movement phrase, her firm, sensual body on display, her bored look recalling a pin-up girl. Context is everything. A fan-kick or split is merely a piece of choreography. It becomes meaningful in performance. It’s the question of who … and where. And, as Mason noted in a post-performance talk Friday evening, each time Antithesis is performed, she considers it site-specific. At home in Colorado, it has been shown in a church, in a strip club, and in someone’s private home. Its re-staging at Dance Place is, she said, unique.

While plenty of female flesh and embedded discourse on the erotic filled the hour, ultimately it felt like Mason and her performers didn’t push far enough. Most believable and most comfortable in their bodies and skin were Essence and Peekaboo and Love. Much was said about how the process challenged the rest of the performers, who worked to allow themselves into new territory, physically and psychically, erotically. As the dichotomous sets of performers merged, late in the show, clad in silky vibrant orange, slacks, dresses, and tunics, Mason returned to her microphone, calling cues for the dancers to physicalize: “hidden,” “surrender,” “play,” “joy,” “chocolate,” “pleasure.” Counting up to ten, the dancers strove to embody in free-form movement those words and ideas, but, like many improvisations, it ended up looking more like moving wallpaper than personal transformation. The dancers, particularly the modern dancers, were still acclimating themselves and their bodies to this new way of thinking and moving — this new erotic consciousness.

One of Lorde’s definitions of the erotic is the “measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.” That final apotheosis, the melding the dancers into a singular unified force, reached for a semblance of utopianism within chaos. And, yet, as this collision of cultures, of bodies, of dancers, that has been occupying the space and lives of its participants, needs to still push further. Mason, her dancers, and dramaturg, Deanna Downes, have described the work as “messy, gritty, tactile, growling, chaotic, passionate and tender.” Antithesis is, in various measures, each of these, for many in the audience. But, no longer the independent artist of her earlier “taboo” days, Mason is now ensconced in the university, and that has taken a toll on her independent, compelling voice. She appears, alas, to have reigned herself in, becoming more self-conscious. Throughout Mason’s career as a choreographer, provocative, even taboo subjects have been an important part of her body of work, most especially wrestling with and coming to terms with identity issues. She has lost some of her youthful boldness, though, in striving to fit into the academic realm (as many independent choreographers have been doing in recent years). Mason’s latest feels trapped in theory: Lorde’s essay and philosophy has too much hold on her.

Photo credit: Kelly Shroads

© 2017 Lisa Traiger

Published January 8, 2017

Long History, Deep Roots for DC Contemporary Dance Theatre

Deep Roots, Wide World

DC Contemporary Dance Theatre/El Teatro de Danza Contemporanea

Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

February 7, 2015

By Lisa Traiger

“Long title and long history,” said Dance Place co-director Deborah Riley to introduce DC Contemporary Dance Theatre, which has also worked under the moniker El Teatro de Danza Contemporanea. Its founder and artistic director Miya Hisaka Silva created the troupe 30 years ago and yesterday’s celebratory program marked the company’s longevity: three decades of making and sharing dance here in Washington and in El Salvador and beyond. The company’s calling card since 1982 has been diversity in its dancers, its choreographers, even its favored genres. The anniversary program, for example, featured contemporary jazz, a balletic pas de deux danced on pointe, hip hop and African-infused jazz and modern dance.

Company co-founder Adrain Bolton, who currently directs a dance ministry in Atlanta, Ga., had two works on the program: 1986’s “Ballet Jazz” and 2013’s “Here and Now.” Both pieces were solid examples of Bolton’s specialty, inspirational jazz technique — the splayed-fingered jazz hands, swooping fan kicks, switching hips, rolling shoulders, arcing bent-legged leaps — with a smattering of balletic influence in amplified arabesques and some classic ballet class footwork braided into the works. Both were sunny, feel good dances, the first featuring the music of Jean Luc Ponty, the second, Luther Vandross — and both were adequately though not spectacularly danced.

Maurice Johnson’s hip-hop infused “When the Day Comes,” for Johnson and six dancers, showed off the performers’ high-energy, fist-pounding, heart-pumping skills in breaking down and drawing the most out of Johnson’s movement sequences with pulsing hips, pumping contractions, snake-y body rolls and booty shakes. Reviving Mexican choreographer Gloria Contreras’s challenging pas de deux from 1995 to Mozart’s Adagio (K622) proved challenging for dancers Max Maisey, the evening’s strongest male partner, and Chika Imamura, who lacked both the turnout and the ruler straight balletic line that the choreography demands.

The program’s centerpiece, and the only world premiere, Felipe Oyarzun’s “Amores Secas,” proved the most interesting and layered work on the program. Dance Place’s Deborah Riley also spoke of the company’s bilinguality — its seamless ability to navigate two nations — the United States and El Salvador — and two cultures. It also tests itself with a multiplicity of embodied dance languages from modern to ballet, jazz to African dance, hip hop to lyrical. There’s an Aileyesque bent to the works and the dancers, not surprising as Hisaka Silva herself has roots in the rigorous Ailey training.

Chilean-trained Oyarzun, currently a graduate student in dance at George Washington University, fuses a vibrant mix of Latin forms in “Amores Secas,” which translates as “Dry Love.” The work is playful, stylish and infused with sensuous tango moves and poses and here the dancers look the most well-rehearsed and comfortable in this playful game of boy-girl tag Oyarzun has set up for five women and three men. One duet unspools when a man in an oversized red sweater encounters his partner and, ultimately, they fuse — each with both arms in the sweater until he parts from her. Will Hernandez has the comic task of valiantly and vainly carrying a plastic rose (which lost its top Saturday night) to woo a partner. The appealing mix of heartfelt love songs, ballads and a zesty up tempo number, all Spanish, added spice to the piece.

Closing the evening Francisco Castillo and Danilo Rivera’s “Restazos de Vida,” featured six dancers in a high energy, glossy study of the African-Latin root dance forms. With a heavy reliance on percussive snaps, contractions and earthy floor work “Retazos de Vida,” which translates as “Fragments of Life,” brought the program full circle, hearkening back to both the company’s jazz and Latin roots. In dance-company years, thirty practically amounts to a lifetime. Founder Hisaka Silva has been a driving force for multicultural dance in the District and beyond, especially in El Salvador during the post-war reconstruction years, by building a company that doesn’t simply create flashy and fun dances but also works of substance that represent the pain-filled stories and difficult histories of El Salvadorans. It was a shame that none of those works, especially “Y ahora la Esperanza” (“And Now for Hope”), a memorial to El Salvador’s 80,000 war dead — even in excerpt form — were included in this anniversary program, because that’s the lasting legacy that DCCDT and El Teatro de Danza Contemporanea should be known for.

This review appeared originally on DCMetroTheatreArts.com and is reprinted here with kind permission.

I heard chatter in the lobby after the show that tap was not an expressive medium to carry forth the heavy message this show imparts. But tap is exactly the appropriate genre to pull back the curtain on America’s long-standing racist and hate-filled roots. With its heavy-hitting footwork by Webb and Edwards, its lighter more nervous tremors from Wilder’s solo performed in prison stripes, to the chorus line of leggy beauties from the Divine Dance Institute, tap is exactly the right means to express the anxiety, fear despair and hope these men represent as they parse through the history of slavery, racism and discrimination in America. REFORM, in ways, reflects and moves past some of the methods and materials in the groundbreaking 1995 musical Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk, of which Wilder is an alum, but REFORM feels more like a sequel, taking audiences further by immersing them in the ramifications of black-men’s actions that are still statistically more likely to land them in jail or dead, than their white counterparts. REFORM is difficult to watch and doesn’t leave audiences with much uplifting. Rather it’s a call to both acknowledgement — particularly for privileged audiences, white or otherwise — and action.

I heard chatter in the lobby after the show that tap was not an expressive medium to carry forth the heavy message this show imparts. But tap is exactly the appropriate genre to pull back the curtain on America’s long-standing racist and hate-filled roots. With its heavy-hitting footwork by Webb and Edwards, its lighter more nervous tremors from Wilder’s solo performed in prison stripes, to the chorus line of leggy beauties from the Divine Dance Institute, tap is exactly the right means to express the anxiety, fear despair and hope these men represent as they parse through the history of slavery, racism and discrimination in America. REFORM, in ways, reflects and moves past some of the methods and materials in the groundbreaking 1995 musical Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk, of which Wilder is an alum, but REFORM feels more like a sequel, taking audiences further by immersing them in the ramifications of black-men’s actions that are still statistically more likely to land them in jail or dead, than their white counterparts. REFORM is difficult to watch and doesn’t leave audiences with much uplifting. Rather it’s a call to both acknowledgement — particularly for privileged audiences, white or otherwise — and action.

And yet, amid all that festivity, there was also deep introspection. What’s Going On is a look inside to reveal where we are — as individuals, as a community, as a nation and a global village.

And yet, amid all that festivity, there was also deep introspection. What’s Going On is a look inside to reveal where we are — as individuals, as a community, as a nation and a global village.

leave a comment