War and (Hope for) Peace

Eleven Reflections on September

Written and directed by Andrea Assaf

Choreography by Donna Mejia

Kennedy Center Millennium Stage

Washington, D.C.

September 15, 2015

By Lisa Traiger

One of the most powerful antiwar statements of the 20th century remains Pablo Picasso’s stunning 1937 oil on canvas, “Guernica.” The painting conveys from its large canvas the atrocities, pain and suffering of war in graphic details of newspaper photo-journalism, shifted through the surrealist lens of Picasso’s cubism.

One of the most powerful antiwar statements of the 20th century remains Pablo Picasso’s stunning 1937 oil on canvas, “Guernica.” The painting conveys from its large canvas the atrocities, pain and suffering of war in graphic details of newspaper photo-journalism, shifted through the surrealist lens of Picasso’s cubism.

“Eleven Reflections on September,” three-dimensionalizes the message of Picasso’s “Guernica,” using poetry, spoken word, original music, video and world fusion dance to bring this message that war garners no true victories into the 21st century. “Eleven Reflections” – part of the citywide Women’s Voices Theater Festival taking place this fall in Washington, D.C. and its surrounding suburbs – draws on the Arab-American experience both pre- and post-September 11. The result is a searing artistic statement of the troubling pain and displacement that occurs when the known world is over taken by the unknown, the uncertainties, the indignities and inequities that happen in war and uprising.

Beginning with a haunting violin and low call of the didgeridoo, flames flickering on the backdrop, poet and spoken world artist Andrea Assaf’s words tumble out. She begins at that brilliant and horrible moment in 2001 when the world changed. The planes and towers were down. Chaos reigned in lower Manhattan and Assaf speaks presciently: “everything that came before was over.” Now there’s a line, a division, a before and after, a moment where Americans in particular realized their vulnerability on the world stage. She speaks of the “smoke of memory” as video captures horrific images of twisted, collapsed buildings.

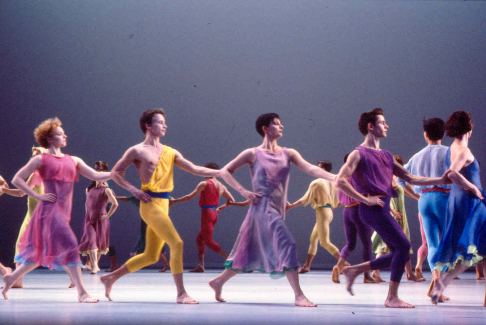

When black-clad dancer Donna Mejia enters, shoulders bare, skirt full and flounced, hair twisted into a topknot, the violin, played by Eylem Basaldi, shimmers, the doumbek played by Natalia Perlaza provides the syncopated beat. And Mejia’s head and shoulders roll, undulating to the beauty of the sound, replicating the wafting smoke alluded to earlier rising into the brilliant, blue sky on that once-gorgeous then horrific September day. Assaf talks of fruit trees, particularly the emblematic olive which takes generations before its pleasant yield can be harvested. Mejia’s arms reach like the branches, then reshape themselves into sharp-elbowed corners – trees cut down, towers downed, souls sacrificed in a split second of insanity and inhumanity.

Choreographically Mejia helps embellish Assaf’s text just as calligraphers often embellish Arabic script into curvilinear designs with graceful arabesques linking and winding into letters, words and verses. In a melding of dance forms referred to as transnational fusion, she draws upon traditions from the Middle East, Asia, North Africa and western modern dance. As letters and words collect on the backdrop in Pramila Vasudevan’s video, Mejia has gathered hip rols and shimmies, arm undulations and shoulder rolls, convulsive contractions of the midsection and torso and deep lunges, her supple body circling above.

Assaf brings forth a basin of water infused with bunches of mint – an act of purifying, of hospitality, of offering. Mejia seems to expand to a haunting wordless chanted call let forth by Luna, then later, she plants both feet firmly into the ground, her solid wise stance an act of ownership and defiance as images of uprising populate the backdrop. The reflections, drawing from the specificity of Assaf’s experiences reified in poetry form the basis for a soul-piercing experiences. While September 11 has had life-changing effects on many aspects of our society and government, “Eleven Reflections” personalizes the act of communal remembrance and also illuminates the specificity of the Arab-American experience.

Mejia’s choreographic contribution to the work allows the words to resonate more fully, underlining and highlighting moments when Assaf’s poetry spurts forward, quickly relentlessly. The dance moments, a shoulder tremor, a head roll, arms twisting, snaking, like the wrapped coils of Mejia’s hair. The elemental mix of these complex dance genres, and the richly evocative world music forms serve to broaden and deepen the viewer’s experience. “Eleven Reflections” with its richly collaborative contributions of singular women’s voices illuminates the antiwar message at the root of Assaf’s poetry. As the poet, clad in black, forges forward, leaving the stage, Mejia takes over. Suddenly her hips tremor and erupt at breakneck speed, the jingling coins of her hip belt punctuating the drum and violin. It’s not merely celebratory, but, more importantly, it’s life affirming.

Picasso overwhelmed viewers with the horrors of war in his politically driven “Guernica.” Assaf’s canvas is equally large and she is not immune to the politics of this moment in time and the resonance of September 11, concomitant uprisings and crises occurring in the Middle East, and beyond. But she and her collaborators don’t wallow in the destruction. In their 21st century multimedia “Guernica,” they recount war’s horrors and the politics of hate, but then push onward, beyond. Amid the death, destruction, protests, and prejudices visited in the piece, blood still courses through veins, muscles still flex, hearts still beat, poetry still rings out. Life, even in the unrelenting grip of war and destruction, goes on and that is the true message “Eleven Reflections on September” leaves viewers to ponder.

Photo: Donna Mejia, by Jen Diaz, courtesy La MaMa

© 2015 Lisa Traiger September 18, 2015

Long History, Deep Roots for DC Contemporary Dance Theatre

Deep Roots, Wide World

DC Contemporary Dance Theatre/El Teatro de Danza Contemporanea

Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

February 7, 2015

By Lisa Traiger

“Long title and long history,” said Dance Place co-director Deborah Riley to introduce DC Contemporary Dance Theatre, which has also worked under the moniker El Teatro de Danza Contemporanea. Its founder and artistic director Miya Hisaka Silva created the troupe 30 years ago and yesterday’s celebratory program marked the company’s longevity: three decades of making and sharing dance here in Washington and in El Salvador and beyond. The company’s calling card since 1982 has been diversity in its dancers, its choreographers, even its favored genres. The anniversary program, for example, featured contemporary jazz, a balletic pas de deux danced on pointe, hip hop and African-infused jazz and modern dance.

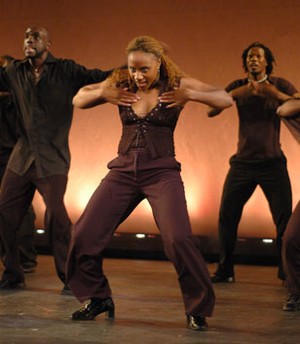

Company co-founder Adrain Bolton, who currently directs a dance ministry in Atlanta, Ga., had two works on the program: 1986’s “Ballet Jazz” and 2013’s “Here and Now.” Both pieces were solid examples of Bolton’s specialty, inspirational jazz technique — the splayed-fingered jazz hands, swooping fan kicks, switching hips, rolling shoulders, arcing bent-legged leaps — with a smattering of balletic influence in amplified arabesques and some classic ballet class footwork braided into the works. Both were sunny, feel good dances, the first featuring the music of Jean Luc Ponty, the second, Luther Vandross — and both were adequately though not spectacularly danced.

Maurice Johnson’s hip-hop infused “When the Day Comes,” for Johnson and six dancers, showed off the performers’ high-energy, fist-pounding, heart-pumping skills in breaking down and drawing the most out of Johnson’s movement sequences with pulsing hips, pumping contractions, snake-y body rolls and booty shakes. Reviving Mexican choreographer Gloria Contreras’s challenging pas de deux from 1995 to Mozart’s Adagio (K622) proved challenging for dancers Max Maisey, the evening’s strongest male partner, and Chika Imamura, who lacked both the turnout and the ruler straight balletic line that the choreography demands.

The program’s centerpiece, and the only world premiere, Felipe Oyarzun’s “Amores Secas,” proved the most interesting and layered work on the program. Dance Place’s Deborah Riley also spoke of the company’s bilinguality — its seamless ability to navigate two nations — the United States and El Salvador — and two cultures. It also tests itself with a multiplicity of embodied dance languages from modern to ballet, jazz to African dance, hip hop to lyrical. There’s an Aileyesque bent to the works and the dancers, not surprising as Hisaka Silva herself has roots in the rigorous Ailey training.

Chilean-trained Oyarzun, currently a graduate student in dance at George Washington University, fuses a vibrant mix of Latin forms in “Amores Secas,” which translates as “Dry Love.” The work is playful, stylish and infused with sensuous tango moves and poses and here the dancers look the most well-rehearsed and comfortable in this playful game of boy-girl tag Oyarzun has set up for five women and three men. One duet unspools when a man in an oversized red sweater encounters his partner and, ultimately, they fuse — each with both arms in the sweater until he parts from her. Will Hernandez has the comic task of valiantly and vainly carrying a plastic rose (which lost its top Saturday night) to woo a partner. The appealing mix of heartfelt love songs, ballads and a zesty up tempo number, all Spanish, added spice to the piece.

Closing the evening Francisco Castillo and Danilo Rivera’s “Restazos de Vida,” featured six dancers in a high energy, glossy study of the African-Latin root dance forms. With a heavy reliance on percussive snaps, contractions and earthy floor work “Retazos de Vida,” which translates as “Fragments of Life,” brought the program full circle, hearkening back to both the company’s jazz and Latin roots. In dance-company years, thirty practically amounts to a lifetime. Founder Hisaka Silva has been a driving force for multicultural dance in the District and beyond, especially in El Salvador during the post-war reconstruction years, by building a company that doesn’t simply create flashy and fun dances but also works of substance that represent the pain-filled stories and difficult histories of El Salvadorans. It was a shame that none of those works, especially “Y ahora la Esperanza” (“And Now for Hope”), a memorial to El Salvador’s 80,000 war dead — even in excerpt form — were included in this anniversary program, because that’s the lasting legacy that DCCDT and El Teatro de Danza Contemporanea should be known for.

This review appeared originally on DCMetroTheatreArts.com and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2015 Lisa Traiger

Global Cooling? Nordic Cool Heats up Washington

Nordic Cool: Iceland Dance Company, Danish Dance Theatre, Carte Blanche, Tero Saarinen Company, Goteborgsoperans Danskompani

Kennedy Center, Washington, D.C.

Feb. 27-March 16, 2013

By Lisa Traiger

Arriving at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., at the end of a relatively mild winter, the dance of Nordic Cool provided sharp, crisp, mind-clearing glimpses of what our northern European compatriots are experimenting with in the dance world. The center has become known and beloved for its multi-arts international festivals: previous years included Arab nations, China, hyper-technology from Japan, and music, dance and arts from India. Under president Michael Kaiser, who leaves the center at the end of 2014, the halls, theaters, galleries, restaurants, terraces and lawn have been filled with music, art, food, poetry, textiles, painting, fabricated objects, and new media. Nordic Cool was no exception, beginning with the oversized wooden moose mounted out front, to the glowing Northern Lights projected onto the white tissue-box like architecture of the building, to hallways filled with elegant clothing, well-designed tableware and furniture, a steam house and a display of Nobel Prize winners, to name merely a few.

Primarily the upstairs Terrace Theater, with its smaller stage footprint, was given over to dance companies from Iceland, Denmark, Norway, Finland and Sweden. Evident from the outset, among all of these companies is the sharp contrast with American modern dance. The typical American sunnyness that particularly populates contemporary American modern dance – think Morris, Tharp, Taylor’s brighter pieces, Parsons, etc. – is foreign to the nature of at least these Nordic dancemakers. There’s a greater cool contemplativeness – not that American works don’t have their own depth and inner turmoil, but in general there’s a can-do, feel-good aspect of dance that dance can change us or influence change that comes through in much American-made dance that I didn’t find in the Nordic companies’ works. Yes, there are struggles, but Americans (see Ailey, Bill T. Jones, et al) more often overcome those struggles and rise above the pain expressed in their works.

Nordic dance takes a different tack. In Iceland Dance Company’s Frank Fannar Pedersen’s “Til,” a clothesline hung with collared shirts and a transparent barrier provide the emotional distance for a sharply etched duet that rises from some finely gentle moments into a flailing breakthrough with a mélange of music, including Sigur Ros and Philip Glass. The nine-member troupe’s centerpiece, “The Swan,” carried in its very title, of course, a heavy load of ballet history dating back to ballet forbears from Petipa to Fokine.

Choreographer Lara Stefansdottir has re-imagined her female swan as a powerful 21st century woman. Tall, with muscular thighs and eyes circled in dark shadows, this swan is no retiring beauty waiting for her curse to be lifted by a beloved prince. Ellen Margret Baehrenz’s post-modern net tutu looks more punk than Petipa. She’s joined on stage by a retiring male companion, Hannes Egilsson, curled up dreaming (echoes of “Spectre de la Rose”?) in a clear, egg-like chair from which he tumbles to the floor. Egilsson is no match for Baehrenz’s pursuit and she pushes, struggles and wrestles him into submission; he becomes the one with the aching beautiful arched wings and undulating shoulders in a reversal of the expected roles of a female submissive swan and her caretaker prince. Then a jarring switch to Prokofiev (the balcony scene from “Romeo and Juliet” of all things) and a shower of snow signals a new reality: Egilsson makes his way back to his cocoon-like chair. This fairy tale is one of breaking away, gaining independence. A new swan for a new 21st century.

The Icelandic evening closed with a flashy, catchy work part urban street dance, part pop star video, “Grosstadtssafari” [Big City Safari], with its sexy, cool hip thrusts, leg kicks, endless spins and leather-and-lace costume is, if nothing more, an audience pleaser for the television dance crowd.

Norway’s Carte Blanche brought Israeli choreographer Sharon Eyal’s assertive dissection of the walk. As she put it in the program note: “In recent works I have used a system of walks. For me walks are the new dance.” In some ways she’s very much the post-modernist, stripping away technique to suss out new discoveries full of unexpected detail, namely large choral group sections of army-like rigor, quirky yet memorable gestures – elbows and fists curled into a boxer’s unreleased punched – and a driving score by Israeli DJ Ori Lichtik that toggles from David Byrne to Claude Debussy, David Lynch to Ol’ Dirty Bastard to Aphex Twin and more. Like “The Swan” from the Icelandic group, “Corps de Walk,” too, plays on the balletic tradition of a corps de ballet – the ballet’s body of dancers crafted to dance, of course, as a single unit. And Eyal highlights that uniformity in the sleek white unitards with white caps the dancers wear, as well as the eye-blanking white contact lenses they don. But the Carte Blanche dancers move like Amazons, creatures acclimated to a harsh climate, but able to surmount any obstacle. They lunge, thrash, punch, push, leap and crawl like as yet discovered creatures of some unknown harsh environment. But at the base of the work by Eyal, house choreographer for Israel’s renowned Batsheva Dance Company, is the walk, asserting the ever-present forward-goingness of the work. They move like ants, purposeful, synchronized in lock step. Carte Blanche’s dancers – an international group of 13 of varying body types and movers – are in one sense an anti-corps. But they have Eyal’s signature style so deeply etched in their bodies that they are formidable as a united front.

The oddball out among these Nordic troupes proved to be Danish Dance Theater. Directed by Brit Tim Rushton, whose pedigree is Royal Ballet, he brought the U.S. premiere (like nearly all of the other works) “Love Songs.” An evening-length work that mines a song book of cherished American jazz classics from Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughn, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, the work follows the score’s trajectory of love discovered, lost, found, and explored in a somewhat dark nightclub-like setting. The dozen dancers are easy going movers who pair up, spar, undulate and separate, their legs rock solid, their abs steely. There’s a relaxed looseness, not quite the uber-popular release technique so big for years now here in the U.S., but the dancers display an ease in the way they curl into themselves or unfurl. The costumes, street (or make that club) clothes, then eventually lingerie, proved serviceable. Odd, though, was the choice of singer. These American classics have been interpreted here by Danish jazz artist Caroline Henderson. Frankly, I longed for the originals from many, including Dusty Springfield’s “I’m Gonna Leave You” and the Arlen/Mercer classic “Come Rain or Come Shine.” Ultimately, “Love Songs” did what it set out to: trace an arc across various couples and individuals in this small community of lovers and friends. What it didn’t do, though, was draw the viewer in to care sincerely about these characters. They were just so many bodies, mixing it up – albeit beautifully – on stage, yet with not much to say. And, frankly, the work had such an “American accent,” created by a British choreographer, no less, that it felt odd in a festival called Nordic Cool.

I can’t tell you much about what dance in Finland looks like. Former Finnish National Ballet dancer Tero Saarinen has traversed the world soaking up ideas from across Western Europe and Japan, where he studied traditional Japanese dance and Butoh. That contemplative quiet rests at the center of the three works his eponymous Tero Saarinen Company brought to the larger Eisenhower Theater. “Westward Ho!” is meant to evoke a seafaring friendship among three men. Saarinen’s signature work, the first he created for his company back in 1996, is oddly picaresque. These three men embark on a journey clad in loose fitting white and little black aprons. They process through the stage to the oddly chosen score by Gavin Bryars and Moondog’s “The Message.” At times they’re weirdly quirky, with Buster Keaton-esque walks. But the continuous nature of the work with its small simple gestures and unadorned moments feels both very particular and sometimes inexplicably painful. The men stopping along the way bears a sense of great import – a spiritual connection, perhaps, aligned with the scratchy vocals of “Jesus’s Blood Never Failed Me Yet,” which sounds like it was recorded in the London Underground. There’s an aura of gravity, even in some of the goofy moments along the way, which solemnly settles into closure as Mikki Kunttu’s lights fade.

Saarinen himself danced in “Hunt,” a 2002 re-envisioning of the great centennial masterpiece “The Rite of Spring.” The score, of course, holds primacy for nearly every choreographer who tackles it. But here Saarinen strips the work of its original sacrificial scenario and instead draws on the multimedia contributions of Marita Liulia, who has spliced together a non-stop parade of moving images from primitive carvings, animals, and futuristic slides. Saarinen opens circling, his bare chest rippling, wing-like arms undulating. Later a winged skirt-like cape drops down, which he dons to provide a projection for the ever-changing collages of images. Strobes pulsate; the music and his movement heighten; he leaps, thrashes and, finally, ultimately, collapses. This “Rite” then becomes a commentary on the overwhelming nature of our multisensory universe and how we sacrifice ourselves, our true bodies, to the moving image, where images are non-stop and the future is constantly rushing toward us, dehumanizing humanity into pods of video and audio bytes rather than flesh and blood. It’s perhaps not a “Rite of Spring” for the ages, but it is one for right now.

Also at the Eisenhower, Sweden’s GoteborgsOperans Danskompani is a smart looking ensemble of 14, which brought three works, including a chic “OreloB” by Finnish dancemaker Kenneth Kvarnstrom. The Ravel score gave away the title – Bolero spelled backwards – yet we only heard faint snatches of it wafting through Jukka Rintamaki’s electronic accompaniment. Dressed in Helena Horstedt’s black leotards adorned with yards of pleated ruffles, the women especially looked Vogue ready. Oddly though, Jens Sethzman’s set included a black garage-like trap door on one side of the stage that opened and closed for no apparent reason. The choreography filled the stage with spirals and swirls of movement, as dancers rose and melted. A few heated partnered moments ramped up the sex appeal, but while the costumes and movement remained rather static, the cacophony of music built to a crash and the “go to” ending, when a choreographer runs out of ideas these days, an onstage snowfall — in this case the snow was an attractive silver.

An onstage pianist, Joakim Kallhed, accompanied Orjan Andersson’s “Beethoven’s 32 Variations,” which included fine, if undefined dancing for four women and four men, which showed adeptness of technique and attack, but little of real substance to capture one’s imagination. The colorful hipster jeans and t-shirts by Catherine Voeffray suggested a casual off-the-cuff tone for Belgium-trained choreographer Stijn Celis’s “You Passion Is Pure Joy To Me,” yet Nick Cave’s heavy handed songs and scratchy vocals lent a gloomy air to the work, which seemed more like a structured improv, where dancers run here, or there, or back again, with little connection to the Cave, Pierre Boulez, Gonzalo Rubalcaba and Krzysztof Penderecki soundtrack, rather than a well-planned piece of choreography.

So, back to the question: how do they dance in Nordic countries? Well, certainly, not like ballet dancers anymore, at least from the selections brought to the Kennedy Center. Many of these companies, among them Iceland Dance and the Goteborgs Operans Danskompani, previously based their works on ballet technique and tradition, but both have thoroughly assimilated the contemporary dance idiom. It’s not exactly American modern dance, although there are elements that seem very American. Yet, these companies approach their work with a more theatrical than choreographic bent, perhaps because in northern Europe still, funding isn’t as challenging as it is in the U.S. American dancemakers maybe rely more on pure choreography and less on lighting, digital, and other special effects for their climactic moments – even fake snow is expensive in these parts. But no matter what these five companies dance, they each performed with a technical proficiency and potency for movement that was refreshing to watch and, indeed, the cool factor of second guessing what contemporary dance from Finland or Norway looks like was very much part of the fun of Nordic Cool.

This piece originally appeared in the Summer 2013 print edition of Ballet Review and is reprinted here with kind permission. To subscribe, visit Ballet Review.

(c) 2013, Lisa Traiger

Defiance and Strength

Voices of Strength: Contemporary Dance & Theater by Women from Africa

Kennedy Center Terrace Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 4-5, 2012

By Lisa Traiger

There’s nothing subtle or understated about the eight women who comprise “Voices of Strength: Contemporary Dance & Theater by Women from Africa,” two programs that made the rounds of the U.S. on a tour produced by MAPP International this past fall. The two-night stop at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater proved exhilarating, enlightening, entertaining and frustrating – sometimes at various moments, other times all at once. What these programs were not were forgettable. The comic duo Kettly Noel and Nelisiwe Xaba, from Mali by way of Haiti and South Africa, respectively, makes dagger-like satire of female obsessions with fashion, male-female relationships, power and individuality. What initially appears to be a light-hearted romp about appearances transforms into something far meatier. Slim, chic, turbaned Noel begins Correspondances with her morning ablutions: surveying a closet of dresses and interchangeable black stiletto heels, checking her lipstick, peering critically into a mirror. Xaba enters from the audience, dragging a battered suitcase behind her. She, too, changes her shoes and outfit. They circle each other, warily sizing up the competition. Later, one manipulates a marionette and states, “I am a woman, fragile but strong inside.”

The two relate what money can by: diamonds, petrol, couture, power – unspoken, but not overlooked is the insinuation that they have none of those material goods. Finally, both strip to leotards, Noel calling out in her native French lists of ballet terms, which Xaba furiously tries to execute, undercutting the rarified vocabulary created by royalty into a mishmash of crudely and comically executed steps. The piece ends in a riot of spilled milk. As the Eurhythmics’ “Sweet Dreams” pulses, the two pull on udder-like containers of milk dropped down from the rafters. Correspondances is a messy, uninhibited navigation of the many landmines women – especially African women, they seem to suggest — face – from appearances to the strictures of expectations to serve others to their own desire to assert power in the still male-dominant culture. That they accomplish their task with droll humor makes it all the more engaging.

There was nothing playful about Quartiers Libres by Ivory Coast’s Nadia Beugre. The work is a bold indictment of Western culture, power, and politics – as powerful and unrelenting as Correspondances was fun and goofy. Performed before a shimmering curtain of empty plastic water bottles, designed by Laurent Bourgeios, Beugre, too, breaks the fourth wall. Entering from a seat in the audience, she carries a microphone, whose cord is draped around her, first like a necklace, later, though, it become a noose. There, after singing and meandering, she finds herself in row C near the stage, where she stares down a woman. After moments of silence the onlooker (a plant?) acquiesces and removes the cord, releasing Beugre’s shackles. But the dancer remains bound, in her silver sling-backs and skin-tight dress, which she wears uncomfortably.

After stripping away her costume to gain a semblance of physical freedom on stage later she squeezes herself into a suit made from more water bottles – becoming a prickly, 21st century porcupine – one with an environmental subtext about overuse of plastic bottles. Finally, Beugre gazes unforgivingly at the audience, brusque, eyes narrowed, confrontational, she stands there. Then she crumples and shoves large black plastic garbage bags into her mouth, her cheeks inflating like a chipmunk’s. From the audience as this continues incessantly: occasional giggles of discomfort. The air is tense, charged – will she suffocate? gag? when will she stop? – and, finally, after an interminable wait, she pulls them out then stands, spent. For her bow, Beugre remains defiant, piercing the air with a peace sign. The work hearkens back to both that of politically confrontational performance artists like Holly Hughes and Karen Finley in its bold and unvarnished approach as well as to the post-modernists a generation before them. Interestingly, both pieces feature high heels as an expression of women’s captivity and powerlessness – the stiletto is the new 21st century pointe shoe, perhaps.

Maria Helena Pinto from Mozambique is also defiant, dancing the entirety of Sombra with a bucket on her head, a bold metaphor asserting unequivocally her right to be seen and heard. To a voiceover in French and Portuguese, she navigates a row of upturned buckets, teetering atop them as if walking a tightrope. She straps on a baby carrier, swaying her hips at one point, unleashing a momentary tango at another. Weaving through buckets hanging from the ceiling with no visual cues, Pinto seems invincible, conquering adversity blindly her head trapped in that bucket yet taking each step boldly. Then the fury unleashes, she scatters buckets everywhere, flinging the one from her head. Finally, free we hear, in French, her last plea: “Give me light, look at my face, enlighten me.”

Morocco’s Bouchra Ouizguen brought the raucous and freewheeling Madame Plaza set on four ample women of a certain age, who first appear reclining on divans, staring and languidly shifting positions. More matronly than dancerly, with bellies and full backsides, flabby arms and double chins, these women have little apparent technical dance training, but a lifetime of experiences filter through in their performance. This harem-like setting becomes a place of calm repose and of refuge, as well as a place to act out and fantasize about relationships. They uses their voices to chant – sometimes it’s a singsong melodic phrase, or a vocal alarm, other times it becomes laughter.

They experiment rising, falling into the floor and rolling, using their hefty weightedness to full effect. At one point one of the women dons a man’s jacket and fedora and a couple acts out a male-female scenario, but they emasculate the “man” who promenades one of the other women around, body to body, appearing at once intimate, entirely natural, and awkward. The piece meanders, time expanding, seeming to stand still, ultimately ending as it began, with the women seated on the divans. Madame Plaza is a reclamation of a woman-centric space as a place to be safe, nurtured, protected, and free to explore creativity and imagination away from the male gaze. Even with its naïve and outsider approach to choreography and structure, the piece is still a powerful reclamation of the female harem, not as a place of isolation and oppression, but as a way for women to congregate and create a community and assert their voices.

Each of these works provides a glimpse into the issues and problems that women across the continent of Africa may face. These women have an outlet: dance, which speaks provocatively and with uncanny directness. David Landes, a Harvard University professor and author of The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, notes, “To deny women is to deprive a country of labor and talent ….[and] to undermine the drive to achievement of boys and men.” These women have asserted their voices.

That dance serves as their means of exploration and expression is not surprising. While each of their works speaks through modalities of modern, post-modern and contemporary dance, the issues they struggle with are age-old. Although some of their methods might seem naïve or old-fashioned (in the 20th-century sense) to jaded American dance goers, promoting democracy and equality for all remains constant

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2012-13 issue of Ballet Review, p. 9. To subscribe to Ballet Review, send a check ($27 for one year, $47 for two years) to: Ballet Review Subscriptions, 37 W. 12th St., #7J, New York, NY 10011.

© 2012 Lisa Traiger

A Personal Best: Dance Watching in 2012

Like many, my 2012 dance year began with an ending: Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Much was written on the closure of this 20th-century American treasure after more than 50 years, especially its final performance events on the days leading up to New Year’s Eve 2012. At the penultimate performance on December 30, the dancers shone, carving swaths of movement from thin air in the hazy pools of light spilling onto raised platform stages in the cavernous Park Avenue Armory space. A piercing trumpet call emanated from the rafters heralding the start of this one-of-a-kind evening. Pillowy, cloud-like installations floated above in near darkness. Throughout, snippets of Cunningham choreography – I saw “Crises,” “Doubles” and maybe “Points in Space” – came and went, moving images played for the last time, while audience members sat on folding chairs, observed from risers or meandered through the space, taking care not to step on the carpeted runways that the dancers used to travel from stage to stage.

I found it refreshing to get so close to the dancers after years of partaking of the Cunningham company in theatrical spaces, for me most commonly the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. Here the dancers became human, sweat beads forming on their backs, breathe elevated, hair matting down toward the end of the evening. Duets, trios, groups formed and dissolved in that coolly unemotive Cunningham fashion, with alacrity they would step off the stage and rest and reset themselves before coming back on again for another round of the complex alphabet of Cunningham bends, pelvic tilts, lunges, passes, springs, jumps and playful leaps. While the dancers energy surged, I felt time was growing short. The end near. I soon found myself on a riser standing directly above and behind music director Takehisa Kosugi who at the keyboard conducted the ensemble and held an digital stop watch. Journalists traditionally end their articles with – 30 –. Here, momentarily I got distracted with the numbers: 41’38”, 41’39”, 41’40”, 41’41” … And then within a minute Kosugi nodded and squeezed his thumb: at 42’40”. An ending stark, poignant, and by the book.

In January, the Mariinsky Ballet’s “Les Saisons Russes” program was an eye opener on many levels. The work of Ballets Russes that stunned Paris then the world from 1909 through 1914 under the astute and market-savvy vision of Serge Diaghilev, remains incomparable for audiences today. The triple bill of Mikel Fokine works wows with its saturated colors and vividly wrought choreographic statements, impeccably executed by Mariinsky’s stable of well-trained dancers. These three ballets – “Chopiniana” from 1908, and “The Firebird” and “Scheherazade” from 1910 – continue to pack a powerful punch, a century after their creation. The subtle Romanticism distilled with elan by the Mariinsky corps de ballet — from the perfection etched into their curved arms and slightly tilted heads, their epaulment unparalleled — makes one pine for a bygone Romantic era that likely never actually attained this level of technical grace and precision. With “Firebird,” the Russian folktale elaborately retold in dance, drama and vibrantly outlandish costumes, the flamboyant folk characters were part ‘80s rock stars, part science fiction film creatures. Finally, the bombast and melodrama of the Arabian Nights rendered through Fokine’s version of “Schererazade” danced as if on steroids provided outsized exoticism, with more sequined costumes, scimtars and false facial hair and the soap operatic performances to suit the pompous grandeur of the Rimsky-Korsakov score. Surely Diaghilev would have approved.

Also in January, Mark Morris Dance Group returned to the Kennedy Center Opera House with its brilliant L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, danced with humanity and glee to Handel’s oratorio, itself based on 17th-century pastoral poem by John Milton and the watercolor illustrations of William Blake. Morris – and Milton, Blake and Handel – each strove for a utopian ideal. This work draws together its disparate parts into one of the great dance works of the 20th century. Enough has been spoken and written about this glorious rendering in music, with the full-voiced Washington Bach Consort Chorus, wildly overblown and softly understated dancing from an expanded company of 24 elegant and spirited movers, and set design – vivid washes of color and light in ranging from flourish of springtime hues to fading fall colors — by Adrianne Lobel. L’Allegro was produced abroad, in 1988 when Morris and his company were in residence at the Theatre Royale de la Monnaie in Belgium, at a time and a place when dance received unprecedented financial and artistic support. I was struck by the open democratic feeling of the dancers, each on equal footing, soloists melding into groups, humorous bits shifting to serious interludes, no dancer stands out individually. For Morris, whose roots date back to folk dance, the community, the group, the natural feeling of people dancing together is valued above the singularity of solo dancing. It’s democracy – small d – at its best. Watching the work again this year, as dance companies large and small balance at the edge of a seemingly perpetual fiscal cliff, was a reminder of how small and cloistered American modern dance has become. We have few choreographers with the resources and the daring to attempt the bold and brash statements that Morris harnessed in L’Allegro.

Another company that leaves everything on stage but in an entirely different vein is Tel Aviv’s Batsheva Dance Company, which I caught at Brooklyn Academy of Music in March. Hora, an evening-length study in gamesmanship and internalized worlds made visible was created by company artistic director (and current world-renowned dance icon) Ohad Naharin. With his facetiously named Gaga movement language, dancers attained heightened sensitivity, not dissimilar to the work butoh masters and post-modernist strove for in earlier decades. And yet the steely technical accomplishment and steadfast allegiances to dancing in the moment that Gaga pulls from its best proponents makes Batsheva among the world’s most prized and praised contemporary dance companies. At BAM, the 60 minute work with its saturated colors and pools of shifting lighting by Avi Yona Bueno and music arranged by Isao Tomita featuring snippets from Wagner, Strauss, Debussy and Mussorgsky offers a smorgasbord of familiarity as the dancers parse oddly shaped lunges with hips askew, pelvises tucked under, ribs thrust forward and heads cocked just so. Odd and awkward, yet athletic and graceful, and undeniably daring Naharin mines his Batsheva dancers for quirks that become accepted as fresh 21st century bodily configurations. Though named Hora, the work has nothing whatsoever to do with the ubiquitous Jewish circle dance, yet after an evening with Batsheva, it’s hard not to feel like celebrating.

Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz in “Necessary Weather,” with lighting by Jennifer Tipton, photo: Stephanie Berger

In April, Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz glimmered in “Necessary Weather,” a subtle tour de force filled with small moments of great and profound drama and even, unexpectedly, a smile or two. The glide of a foot, cock of a head, even a raised eyebrow or tip of a hat from Rudner and Reitz resonated beneath the glow of Jennifer Tipton’s lighting, which in American Dance Institute’s Rockville studio theater, performed a choreography of its own glowing, fading, saturating and shimmering.

Also at ADI in May, Tzveta Kassabova created a rarified world – of the daily-ness of life and the outdoors. By bringing nature inside and onto the stage, which was strewn with leaves, decorated with lawn furniture, and, in a coup de theatre, a mud puddle and a rain storm. Her evening-length and richly rendered Left of Green, Fall, choreographed on a wide-ranging cast of 16 child and adult dancers and movers, featured sound design and original music with a folk-ish tinge by Steve Wanna. The work tugs at the outer corners of thought with its intermingling of hyper-real and imagined worlds. The senses also come into play: the smell of drying leaves, the crackly crunch they make beneath one’s feet and the moist-wet smell of fall is startling, particularly occurring indoors on a sunny May afternoon. Kassabova, with her flounce of bouncy curls and angular, sharp-cornered body, dances with a laser-like intensity. She’s ready to play, allowing the sounds and sights of children in a park, sometimes among themselves, other times with adults. She’s also game to show off awkwardness: turned in feet, sharp corners of elbows, hunched shoulders and flat-footed balances – providing refreshing lessons that beauty is indeed present in the most ordinary and the most natural ways the body moves.

The Paris Opera Ballet’s July stop at the Kennedy Center Opera House brought an impeccable rendering of one of the pinnacles of Romantic ballet: Giselle. And should one expect anything less than perfection when the program credits list the number of performances of this ballet by the company? On July 5, 2012, I saw the “760th performance by the Paris Opera Ballet and the 206th performance of this production,” one with choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot dating from 1841, transmitted by Marius Petipa in 1887 and adapted by Patrice Bart and Eugene Polyakov in 1991. Two days later it was 763. The POB still uses the 1924 set and costume designs of the great Alexandre Benois, adding further authenticity to the work. But nothing about this production is museum material. POB continues to breathe life into its Giselle.

Aside from making a pilgrimage to the imaginary graveside of the tragic maiden dancer two-timed by her admirer, it’s hard to find a more accurate and handsome production of this ballet masterpiece. Aurelie Dupont was a thoughtful and sophisticated Giselle, care and technical virtuosity evident in her performance, while her Albrecht, Mathieu Ganio, played his Romantic hero for grandeur. While the 40-something husband and wife duo of Nicholas Le Riche and Clairemarie Osta on paper make an unlikely Albrecht and Giselle, in reality their heartfelt performances were so intensely and genuinely realized at the Saturday matinee that they felt as youthful as Giselles and Albrechts a generation younger.

The production is as close to perfection on so many levels that one might ever find in a ballet, starting with a corps de ballet that danced singularly, breathing as one unit, most particularly in the act II graveside scene. The mime passages, too, were truly beautiful, works of expressive artistry many that in most companies, particularly the American ones, are dropped or given short shrift. Here the tradition remains that mime is integral to the choreography, not an afterthought but a moment of import. Most interesting was a (new to me) mime sequence by Giselle’s mother about the origins of her daughter’s affliction and how she will most definitely die (hands in fists, crossed at the wrists, held low at the chest). Later when the Wilis dance in act II, it becomes abundantly clear why their arms are crossed, though delicately, their hands relaxed: they’re the walking dead, zombies, if you will, of another era. Another unforgettable moment in POBs Giselle, is its use of tableaux at then ending moment of each act. Each act ends in a moment of frozen stillness – act one of course with Giselle’s death, act two with the resurrection of Albrecht. Each of these is captured in a stage picture, then the curtain dropped and rose again – and there the dancers stood, still posed in character. Stunning and memorable.

Each year in August the Karmiel Dance Festival swallows up the small northern Israeli city of Karmiel as upwards of reportedly 250,000 folk and professional dancers swarm the city for three days and nights of dance. From large-scale performances in an outdoor amphitheater to professional and semi-professional and student companies performing in the municipal auditorium and in local gymnasiums and schools to folk dance sessions on the city’s six tennis courts, Karmiel is awash in dance. I caught companies ranging from the silky beauty of Guangdong Modern Dance Company from China’s Guangzhou province, France’s Ballet de Opera Metz under the direction of Patrick Salliot, the youthful and vivacious CIA Brasileira De Ballet, where artistic director Jorge Texeira seeks out his youthful dance protégés from the streets and barrios of some of the poorest neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, Terrence Orr’s Pittsburgh Ballet Theater, and Israel’s Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, directed by Rami Be’er in a program of new works by young dancemakers. Maybe not the best that I saw, but the unforgettable oddity of the three-day festival was the headlining company, billed as the Cossack National Dance Troupe from Russia. In the grand folk dance tradition of the great Moiseyev company of Russia, these dancers, musicians and singers – numbering 60 strong – let the sparks fly, literally. With breathtaking sword play where white hot sparks truly did fly from the swords, to astounding acrobatic feats and graceful, feminine dances featuring smoothness, precision and delicate footwork parsed out in heeled character boots, the troupe was a hit. Few in the appreciative Israeli crowd – many of whom sang along to the old Russian folk songs buying into a mythic pastoral vision of the Cossack warriors – seemed aware of the irony of an audience of predominantly Israeli Jews heartily applauding a show titled “The Cossacks Are Coming!” The last time Jews were heard to say “The Cossacks are coming,” things didn’t turn out so well.

In September, Dance Place was fortunate to book one of the State Department’s CenterStage touring troupes at the top of its season. Nan Jombang, a one-of-a-kind family of dancers from the Indonesian island of Sumatra, provided a remarkable and moving evening in its North American premiere. Rantau Berbisik or “Whisperings of Exile” begins with a siren call, a female shriek that’s an alarm and cry of pain, that begins a journey of unexpected images. Ery Mefri, a dancer from Padang, on the western coast of Sumatra, has created a surprisingly original dance culture drawing from traditional tribal rituals, martial arts – randai and pencak silak – captivating chants and unusual body percussion techniques. But most unique about Mefri’s artistic project, and the company he founded in 1983, is that it is truly a family affair: the five dancers are his wife and children. The live, sleep, eat and work together daily in intense isolation crafting dances of elemental power and uncommon dynamism through an intensely intimate process.

The work features a trio of gloriously powerful women who exhibit strength of body and will in the earthbound manner they dive into movement, oozing into deep plie like squats and then pounding the taut canvas of their stretched red pants like drummers. Moments later they spring forth from deep lunges, pouncing then retreating, only to strike out again. The hour-long work is filled with mystery and mundanity: dancers carry plates and cups back and forth from a tea cart, rattling the china in percussive polyrhythms, and one woman sits in a chair and keens, rocking and hugging herself for an inconsolable loss. Later the women pass and stack plates around a wooden table with an urgency and assembly-line precision that brings new meaning to the term woman’s work. The one thin boy/man in the group attacks and retreats with preternatural grace, sometimes part of this female-dominated social structure, other times apart – an outcast or loner. And throughout amid the bustle, the urgent calls, the unmitigated pain and sense of loss, there remains a stunning impression of yearning, of hope. The ancient rituals of home and hearth, of work and rest, of group and individual it seems are drawn from a language and way of life that Mefri sees disappearing. Quickly evident in this riveting evening is how Mefri and his family can communicate so deeply to the heart and soul in ways that strike at the core, of unspoken truths about family, community and cultural continuity and conveyance.

One final note of continuity and cultural conveyance was struck resoundingly in December with Chicago Human Rhythm Project’s “Juba: Masters of Tap and Percussive Dance” at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. While the program was long on youth and short on masters – an indication that we’ve reached the end our last generation of true tap masters — Dianne “Lady Di” Walker represented the early tap revival providing the link to old time rhythm tap of the early and mid-20th century. The program, emceed and curated by Lane Alexander of CHRP, brought together a bevy of youthful dance companies, among them Michelle Dorrance’s Dorrance Dance with an interesting excerpt for two barefoot modern dancers and a tapper. D.C. favorite Step Afrika! brought down the first act curtain with its heart-raising rhythms and body slapping percussion. And, closing out the evening, Walker served up “Softly As the Morning Sunrise,” a number as smooth and bubbly as glass of Cristal, her footwork as fast as hummingbird wings, her physics-defying feet emitting more sounds than the eye could see. This full evening of tap also included Derik Grant, Sam Weber, and younger pros Jason Janas, Chris Broughton, Connor Kelley, Jumaane Taylor, Joseph Monroe Webb and Kyle Wildner. The evening with its teen and college aged dancers sounded a note that tap will continue to be a force to reckon with in the 21st century. That it occurred on a main stage at the Kennedy Center was – still – a rarity. Let’s hope the success of this evening will lead to more forays into vernacular and percussive dance forms at the nation’s performing arts center. The clusters of tap fans young and old gathered in the lobby after the show couldn’t bear to leave. If they had thrown down a wooden tap floor on the red carpeting, no doubt folks would have stayed for another hour of tap challenges right there in the lobby.

***

And I can’t forget a final, very personal experience. During the annual Kennedy Center run of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in February, I found myself pulled from my aisle seat to join the dancers onstage in Ohad Naharin’s “Minus 16,” which the company had just added to its repertory in late 2011. Clad in slim fitting business suits and stark white shirts, the dancers make their way to the lip of the stage and stare. The next thing you know, they’re stalking the aisles, climbing over seats, crawling across laps to bring up randomly selected members of the audience. The sequence is fascinating – a mix of the mundane, the ridiculous and the dancerly – inviting in the human element as these god-like dancers canoodle, slow dance, cha-cha and indulge their new-found partners. Soon they corral the group, circle, and in ones and twos the dancers begin to lead the participants off stage, leaving just one – most frequently a woman – standing in the embrace of her partner as the others hug themselves in a smug slow dance. On cue the dancers fall. The woman remains alone, in the spotlight. Frequently aghast, embarrassed, she slinks away.

Dreamlike is the best way I can describe the experience. Audience members seem to be selected according to a particular color, most frequently red judging from the previous times I’ve seen the work. As a “winter” on the color chart, I, of course, frequently wear red from my beret to my purse to a closet full of sweaters and blouses. When the dancers lined up, I felt one made eye contact with me right away. I didn’t avert my gaze and I thought that I could be chosen. But as they came into the audience, he passed me by and I exhaled slightly, relieved not to be selected. The stage re-filled with dancers and their unwitting partners as I watched. Suddenly, the same dancer who caught my eye was at my side beckoning, pulling me from my seat. My hand in his I followed him down the dark aisle and up the stairs. There the music changed frequently from kitschy ‘60s pop to rumba, cha cha, and tango – all recognizably familiar, a Naharin trait. Yet the choreographer definitely wants to keep the novices off guard, which is disconcerting because there are moments when the dancers are completely with you and you feel comfortably in their care, then they leave you to your own devices and all bets are off.

I realized quickly that I had to focus fully on my partner and not get distracted by what others on stage or in the audience were doing. We maintained eye contact throughout and went through a bevy of pop-ish dances: I recall bouncing, lunging, throwing in a bump or two and a great tango – wow, what a lead. Then they mixed things up, pushing all the civilians into a circle then a clump before reshuffling things. Somehow I came out with a new partner and things really heated up as I followed him and he me. I felt my old contact skills tingling back to life as I tried to give as good as he gave. He dipped me and I suspect that when he felt I gave in to it, he realized he could take me further. I don’t know how, but I found myself lifted above his head in what felt like a press. As he turned, I thought I might as well take advantage of this. I’m never going to be in the arms of an Ailey dancer again. I put one leg in passe, straightened the other, threw my head back and lifted my sternum, while keeping one hand on my head so my beret wouldn’t fly. He likely only made two or three rotations, but in my mind it felt like a carnival carousel: incredible. Back on earth with my feet on solid footing, he tangoed and embraced me. I knew what was coming. The slow dance when they lead partners off stage. I realized I might was well give in to the moment, I melted into his embrace and we swayed. Two bodies as one. Eyes closed. I momentarily opened them when I sensed the stage emptying. The only words spoken between us are when I said, “uh oh.” He squeezed me and then dropped to the floor in an X with the remaining Ailey dancers. There I was. Alone. Center stage in the Kennedy Center Opera House. I have been seeing performances there since I was a child in 1970s. I had seconds to decide what I was going to do. “%^&#) it,” I said to myself. “I’m standing here in the Opera House with 2,500 people looking at me. I’m going to take my bow.” I moved my leg into B+, opened my arms with a flourish, dropped my head and shoulders and rose, relishing the moment for all it was worth. Seconds later, the audience roared. I was stunned. I made my way gingerly off stage, still blinded by the spotlights as I fumbled up the aisle to find my seat.

Dreamlike. Throughout I knew this was something I would want to relish and remember and tried to find markers for while maintaining the presence of the moment. I was able to find out who the dancers were (yes, there were two) who partnered me. But I believe that Naharin wants the mystery to remain both for the onlookers and the participants. At intermission people were asking if I was a “plant,” insisting that I must have known what to do in advance. But, no, Naharin wants that indeterminacy, that edginess, that moment of frisson, when the audience realizes that with folks just like them on stage, all bets are off on what could happen. While we often attend dance performances to see heightened, better, more beautiful and more physically fit and skilled versions of ourselves (one of the reasons, I think, that we also watch football, basketball and the like), there’s something about seeing someone just like you or me up on stage. If the middle aged mom who needs to get the kids off to school then go to work the next morning can have such a rarified experience then maybe, just maybe, the rest of us can rediscover something fresh, untried, daring, out of sorts, amid the banality of our everyday lives. In this brief segment – and I couldn’t tell you how long it lasted, but I’m sure not more than five minutes at most – Naharin, through the heightened skill and beauty of professional dancers, offers escape from the ordinary. Audiences live through it vicariously by seeing one of their own up there on stage. For me the experience was unforgetable.

© 2012 Lisa Traiger

Published December 30, 2012

Israel: A Nation Dances

Karmiel Dance Festival

August 6-8, 2012

Karmiel, Israel

By Lisa Traiger

While summer dance festivals abound and al fresco dancing is near irresistible for audiences and dancers from the United States to Europe and the Far East, I don’t know of any dance festival that not only boasts a customized theme song, but also attract upwards of 250,000 visitors over just three days and nights. Karmiel, a little city that could in northern Israel, has both an upbeat theme song — the Hebrew “Karmiel Rokedet” or “Karmiel Dances” — and hordes of visitors who fill the town, population just shy of 52,000, with dancers young and old, pro and amateur, for a non-stop parade of Israeli folk dance sessions and performances by amateur folk dance troupes and professional dance companies touring on the international circuit.

This year, the dance festival’s 25th, included three evenings of performances August 6, 7 and 8, in a vast outdoor amphitheater, which can seat about 19,000 on chairs and the lawn, plus all-night dance sessions for thousands of folk dancers orbiting in concentric circles on the city’s six tennis courts from midnight until dawn. Then there was a handful of international ballet and modern companies performing in the city’s municipal theater. The festival, founded in 1987 by the city’s first mayor Baruch Venger, was meant to pick up where an earlier Israeli dance festival, the famed Dalia Festival left off. Dalia first brought together Israeli folk dancers during the Jewish festival of Shavuot in 1944. A reported 10,000 people traveled to Kibbutz Dalia to celebrate the wheat harvest with traditional and new Israeli folk dances and displays of other ethnic dances from around the world. Israelis trekked to an outdoor hill on the kibbutz to watch groups perform dances paying tribute to the Biblical land and the region’s agricultural roots, which were being resuscitated into a new Jewish state.

While Karmiel’s heady dance festival is an acknowledgment of Israel’s Zionistic and émigré roots, it has become an event in its own right — and its massive proportions speak to the widespread growth and abiding interest Israel holds in dance across a multiplicity of forms.

Each year the festival opens with a grand showcase featuring some of Israel’s top pop culture icons. This year the opener, overseen by festival artistic director Shlomo Maman, a well-known folk dance choreographer in his own right, honored recipients of Israel’s highest civilian honor, the Israel Prize. The evening of songs and dances reflected the breadth and depth of Israeli cultural, artistic and social contributions to the nation. Dance and song segments honored the nation’s poets including Leah Goldberg, singers like Naomi Shemer and Yoram Gaon, and organizations like the Tzofim, Israeli scouts, and Tel Aviv’s famed Habima Theater Company. Three of Israel’s renowned choreographers — Gurit Kadman (nee Gertrude Kraus), Yehudit Arnon and Sara Levi Tanai, who each left indelible marks on the growing dance culture of the country — were among the honored laureates.

The opening evening was emceed by a jowly singer/actor Yoram Gaon, who bills himself as Israel’s Frank Sinatra, but with his recent foray into Hebrew sitcoms, perhaps he’s more of a precursor to Justin Timberlake. He served up both a nostalgia-tinged glance at Israel’s cultural achievements and examples of the youthful vigor of its earnest younger generation of Israeli dance performers. Accompanied by the Ashdod Andalusian Orchestra, Gaon introduced dances and songs showcasing Israeli culture. For the most part this shifting company of dancers in the folk dance tradition bobbed and weaved in circles and lines, hopping, skipping and leaping to up-tempo horas. The ladies smiled broadly in their swingy A-lined dresses, the men clad in colorful tunics. Among the opener’s highlights was singer Achinoam Nini, better known as Noa, in “Keren Or.” The N.Y. High School of the Performing Arts-trained singer/songwriter draws on her Yemenite ancestry and, of the hundreds of Israeli dancers seen, she was one of a very few who exhibited the distinctive yet restrained shoulder shimmy characteristic of authentic Yemenite dances. The dancing throughout, this opening program, and somewhat less so in the third day’s closer, was mostly performed by well-trained amateurs, teenage and young adult dancers who attacked the choreography with more verve than accuracy, but when close to 100 dancers filled the stage, a faux pas or two really was beside the point. Folk dance in Israel was and for the most part remains, a communal activity that promote group unity even amid the diversity of dances that choreographers churn out year after year — horas, partnered waltzes, debkas, line dances, salsa-tinged Israeli dances and more.

The closing program again featured these spirited amateur dancers, this time displaying a greater variety of dance styles. There were groups that borrowed from Spanish or Russian/Georgian traditions, and fresh-faced teens who looked ready for the U.S. studio competition circuit dancing to Hebrew pop tunes in a style I can only call “Isra-lyrical” for its resemblance to that muddy mix of jazz, modern and contemporary that comprises “lyrical” on our own shores.

The headliner for night two at Karmiel was a stunner for many reasons. The last time Jews exclaimed “The Cossacks are coming!” things didn’t turn out so well. But the Cossack National Dance Troupe from Russia indeed came to Israel and, by measure of the audience reaction, was a terrific hit. The flashy production, actually titled “The Cossacks Are Coming!” featured a chorus, a traditional orchestra with balalaika, and a company of exquisite dancers all told numbering nearly 60. Though unable to understand what the close harmony choir sang about, in a nation that has absorbed more than a million Russian immigrants in a generation, these Russian songs were beloved, and many of them sound suspiciously Israeli (for Israelis are also great copycats, particularly in borrowing shamelessly from foreign genres and even specific songs).

The dancing, including spectacular sword battles where actual sparks flew, soaring leaps and sequences of barrel turns, aerial cartwheels, and that knee pumping katzastky step, draws from Russian folkloric traditions. But its fervid Cossack machismo, along with costumes taken straight from the Red Army, has all the trappings of a martial dance company celebrating war spoils or prepping for a battle campaign. Joined by a lovely complement of women in delicate low-heel character boots, they circled and coupled up, promenading in unison and tandem, the women dainty in their grapevines and polkas, the men ever bold in runs, stomps and leaps. Interestingly, even given the ignominious history of Cossack-Jewish relations, Israelis felt a deep affinity for the songs and dances — many in the audience were singing along, or at least humming some of the anthemic-sounding chorales. Of course, Russian and Eastern European culture — music and dance in particular — was highly influential to those forging new cultural traditions 65 years ago in the young Jewish state. Many of the horas and rambunctious circle dances still carry a distinctive Russian flavor in their choreographic bones. Israel’s popular choral group the Gevatron, with its songs of bucolic Zionism and patriotism and its accordion accompaniment, clearly has its roots in the patriotic and nature-based Russian songs of the Cossack chorus. This odd frisson came over me: the Cossacks made life miserable for Jews in Russia a century ago and yet so many Jews and Israelis continue to hold a warm affinity for the music and dance culture of this period.

But the dance performances at Karmiel weren’t only in the Israeli folk genre or its nostalgic precursor. The Karmiel Festival’s artistic adviser Yair Vardi, who oversees the nation’s premiere dance venue, the Suzanne Dellal Dance Centre in Tel Aviv, programmed a small but interesting selection of foreign ballet and modern companies, which performed not only at the Karmiel Cultural Center, where some shows began at 11:00 a.m. and ran straight through until midnight, but a few companies also performed in Tel Aviv or other cities during their visit.

In a nation with strong European roots, it’s surprising that homegrown ballet hasn’t made inroads to Israel. The mediocre Israel Ballet lacks adequate choreographic vision, and its dancers have fewer opportunities to develop their craft in a nation besotted with modern and contemporary dancers. Thus the visit from the young and vivacious CIA Brasileira De Ballet, where artistic director Jorge Texeira seeks out his youthful dance protégés from the streets and barrios of some of the poorest neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro. The program showcased the dancers in excerpts from two warhorse classics, “Don Quixote” and “Raymonda.” The muddy recorded scores and off-the-rack backdrops luckily were overshadowed by the generous and fresh performances. Energetic and well-trained, the dancers, all between the ages of 18 and 24, showed off their vivacity and dynamic attack. As Kitri, Melissa Oliveira was lovely, playful and flirtatious with her high-kicking grand jetes, while Gustavo Cavalho was a frisky but not unruly Basilio. The technical training of the company from the corps upwards, with strong fifths and landings out of jumps and turns, showed care and precision. I was reminded of the unparalleled strengths of another Latin ballet troupe, National Ballet of Cuba, but these dancers young and still developing display a youthful vigor and consummate joy. The “Raymonda Suite,” while slightly less assured, again showcased that technical care. “Brazilian Suite” was meant to display the dancers in a contemporary work, this one drew references from the hip swaying samba, but with a raft of complex lifts and supports far removed from the classical realm, the overly complicated choreography didn’t allow the dancers to sparkle.

The U.S. was represented by Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre, directed by former American Ballet Theatre dancer and ballet master Terrence Orr. The company, on its first international tour in two decades, was invited because of a sister-city relationship the city’s Jewish Federation has with the city of Karmiel. A boon for the dancers, the tour garnered the company extensive visibility in the press and via social media outlets. The program included Mark Morris’s “Maelstrom,” stunningly danced by the company. The seven couples infused this darker, more somber Morris piece with care and precision. The deceptively simple choreography, set to the Beethoven “Trio No. 5 in D Major, Opus 70,” requires steely attack coupled with an ethereal floating quality. Pure balletic passages, punctuated by a flexion of an ankle or wrist, or a daring toss of a female partner to another male, build to passages of tornado-like runs, the dancers bodies converging into a spinning vortex before the stage empties for a solo or pair of dancers. The evening’s crowd pleaser proved to be Dwight Rhoden’s homage to summer at the beach, “Step Touch,” which featured a recorded score sung by Charlie Thomas and the Drifters and Pure Gold. Think sandy bathing suits, “Under the Boardwalk,” the smell of French fries and salt water taffy. The snazzy, bathing suit-like costumes by Christine Darch set the stage for fun-filled groups of sexy women and buff men to intermingle to some of these summertime standards. The program also featured Balanchine’s “Sylvia Pas de Deux,” well danced by Julia Erickson and Alexandre Silva.

A third ballet company representing the contemporary European tradition, Ballet de Opera Metz under the direction of Patrick Salliot, brought three new takes on works familiar to followers of ballet’s 20th-century canon. Salliot’s re-envisioning of “Daphnis et Chloe” as a love triangle with a homosexual twist was at first inscrutable without knowing the plot change. The choreography has that contemporary Bejart-ian feel in its movement language though at times there’s a Balanchinian sparseness that tempers some of the more overwrought passages. Salliot’s “La Fauness,” featuring the famed Debussy score, updates Nijinsky’s erotic chance forest meeting between a nymph and a faun. The sensuality remains vital in this modern dress meeting of a man and a woman. The female, languidly stretches out in a chair, highly attuned to her body’s sensitivities. A suited man enters as does a second woman. Swooping hugs, sweeping caresses and sensuous lifts and holds heighten the sexual tension among the three. Salliot also refers back to the Grecian two dimensional poses of the Nijinsky but there’s a definite erotic element to the trio.

They closed the program with a reconsideration of “Scheherazade,” featuring the lush Rimsky-Korsakov score and a few episodes from the Arabian Nights tales, told with theatrical finesse using a handful of astute props, particularly a toy sailboat and an oversized swath of silk that became a tent, a sea, and a backdrop for a harem boudoir. The Metz dancers underscored their movement with a lushness and pliancy that kept one’s attention, while the choreography danced with an unmistakable French accent — sensual, expressive, sometimes even overwrought — demonstrated a distinctive take on ballet.

From China’s Guangzhou province, Guandong Modern Dance Company has assimilated primarily American modern dance techniques, but reconfigured them in various interesting ways to speak via movement language with a contemporary Chinese approach. Their program of three works, slated for an 11:00 a.m. time slot, was one of the festival’s stunners. The choreography, often saturated with lighting effects and hazy fog, made the works feel as if they were out of time or unraveling a distant world. The program, titled “Between Body and Soul,” showcased a trio of works, two by the company’s chief choreographer Liu Qi, who has been with Guangdong since 1996, and one by Xing Lang, another former dancer with the troupe. “Touched,” by Xing Lang, featured quicksilver movement by the company of 11, dancers falling and rising, clad in socks and an assemblage of practice clothes. Nearly boneless, their torsos undulating, their arms and feet pliant, the choreography shows the dancers as charged beings that catapult into movement then capitulate in changing mixings and groupings. “Another Voice” seemed to be an excerpt from a larger piece. A trio of dancers were wrapped head to toe in flesh-toned strips of cloth, and moved to the sounds of dripping water as if some sort of forest creatures, wispy, ebbing and flowing, slippery through their ribs and hips. Finally, the closing piece was billed as “Haromim,” which translates to “The Romans.” I believe in actuality this piece was an excerpt from Liu Qi’s “Upon Calligraphy,” with its shape-oriented figurative structures, at once silky and staccato with dancers’ legs develope-ing while elbows and shoulders punctuate a phrase with a slash or a dot of movement. Each of the works was performed with an exquisite sense of silky ease yet total accuracy. Interestingly, for a company drawing on American ideals of modern dance, weightedness and gravitational pull into the floor was eschewed for a sense of weightlessness even as the dancers moved into and away from the floor, an ideal that is anathema to modern dance’s early roots.

Israel’s Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, which was founded in 1970 and remains based on Kibbutz Ga’aton in the western Galilee, presented a trio of very new works on a program titled “Double 3.” Israel’s modern dance roots are more diverse, with early fundamental contributions coming from Martha Graham and Anna Sokolow among other Americans. But the European influence is broad and remains a driving force for many companies, some of whom look toward ideals of tanztheater for inspiration. It has been said that when Pina Bausch came to Israel in 1981, she inspired generations of choreographers. There’s an unusual hybrid in some of the current Israeli contemporary dance that stems from this duel set of influences: American modern and post-modernism (much likely picked up in European cities like Paris, Amsterdam and Berlin) and European tanztheater. The triple bill from the Kibbutz Company, directed by Rami Be’er, only the troupe’s second leader after Yehudit Arnon, is indicative of this trend.

Idan Sharabi, a Juilliard graduate who danced with Netherlands Dance Theatre before returning to Tel Aviv in 2010, premiered the riveting “I Dropped the Ceiling on the Floor Again,” featuring a complex audio collage with voice, music and sound effects including clips from Ravel and Chopin and captured sounds of falling objects. The work begins in darkness with a low, foreboding rumble. A black partial wall at the back of the stage becomes both a backdrop and a hiding place during the piece. The sounds of crashes, breaking glass and dropping objects instigate the dancers to tremor then freeze, crash to the floor and quake. Each boom or drop instigates another rush of movement, then the dancers, each clad in a colorful assortment of street wear, settle into quirky undulations, twists, curves and swipes of movement. One dancer brings on a glass of water, drinks and then the sound of smashing glass intrudes. The work builds and crescendos in a wall of found sound and movement. Some dancers remain frozen while others dash, squat and scoot in a mad rush for the unknown. Though abstract, the suggestion of “…Ceiling” is of the matsav, what Israelis call “the situation,” meaning the current political and attendant turmoil of terrorism that includes, of course, threat of rockets launched regularly at city enclaves like Sderot in Southern Israel. The work feels terrifyingly real — capturing everyday life disrupted, distorted by the precariousness of the unknown, yet seemingly normal on the surface. The sound score with its broken dishes, a wailing child, and other escalating noise adds an overwhelming sense of unease to what remains often unspoken in a nation where its people live so closely to shattering effects.

Company member Oz Mulay’s “Poor-ya” for six dancers features both galumphing full bodied movements and stretchy, sinewy reaches. A collage of piano, music and voice, here provided less direction for the dancers as they roamed and at points found repose. Another company member, Nir Even Shoham, debuted “Day Too Soon,” which relied on similar movement language but felt more suggestive of a journey or a lifecycle, with its six dancers carrying sacks — clothing perhaps? — and performing a series of semaphoric-like gestures that accumulated. The journey, performed before a series of white panels seemed at times arduous and dancers bounced, rocked and sought out momentarily various support from members of the group. At one point the work reverted to a unison section, looking everything like a competition dance, and breaking the mood that had been more artfully and thematically built. The Kibbutz company dancers attack choreography with an unrivaled sense of commitment, an earthiness and a fearless feeling that whatever might come next will be an adventure. A wonderful way to wrap up a dance-centric trip to Israel.

This review was published originally in the Fall 2012 issue of Ballet Review and is reprinted here with kind permission. To subscribe, visit http://www.balletreview.com/.

© 2012 Lisa Traiger

From Zero to 4,678: 60 Years of Israeli Dance at the 92nd St. Y

My story on 60 years of Israeli folk dance at the 92nd Street Y appeared in The Forward:

“In 1924 there was just one Israeli folk dance, ‘Hora Agadati,’ created in Tel Aviv. Within a year of gaining statehood, Israel could boast 75 folk dances. And by 2005 there were 4,678, according to Dina Roginsky, an anthropologist and lecturer at Yale University who has studied the growth of Israeli folk dance. This brings into sharp relief the importance of New York’s Israeli Dance Institute, which is celebrating 60 years of folk dancing from April 1 to 3. Festival 60, presented as a joint venture between IDI and the 92nd Street Y, features workshops and parties at the Y and a festival performance. The program features 300 dancers from 16 groups spanning kindergarteners to senior citizens, who have traveled from Caracas, Venezuela; Toronto; Miami; Washington, D.C., and Albany, N.Y., to perform in the longest-running Israeli dance festival in the world.”

Measures of Masculinity

Multiple Personalities: an evening of dance by Christopher K. Morgan

Music Center at Strathmore

Bethesda, Md.

May 23, 2010

By Lisa Traiger

© 2010 by Lisa Traiger

Dancer/choreographer Christopher Morgan is a shape shifter. “Multiple Personalities,” his recent concert of choreographic works crisscrosses genres as easily as a smooth, flat stone skipped across a glassy pond. A modern dancer, he effortlessly tackled a balletic pas de deux, a hip hop number and a traditional hula. Although that extreme variety sounds suspiciously like a Dolly Dinkle recital, Morgan displays choreographic intellect in each of the genres he assays, resulting in mostly full-bodied artistic works that interplay narrative, movement ideas and a not insignificant trace of humanity.Currently rehearsal director at CityDance Ensemble, one of the Washington, D.C. region’s fastest growing and most successful contemporary companies, Morgan’s evening of works fits neatly into the intimate CityDance Center studio/theater at the Music Center at Strathmore. Opening with a traditional hula song and chant, expanded with a personal story -– a nod to Morgan’s time spent working with Marylander Liz Lerman’s text-based choreographic endeavors -– the evening also featured a contemporary ballet mostly danced on pointe; a freewheeling modern number with allusions to clubbing and high fashion; and, the program’s strongest and most personal piece, “The Measure of a Man,” a testament of the artist coming to terms with his masculine identity.