Love Is in the Air

The Look of Love

Mark Morris Dance Group

John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 26-29, 2022

By Lisa Traiger

One-time maverick choreographer Mark Morris is now mature enough to collect Social Security. In another millennium, way back in 1985, his Mark Morris Dance Group made its Kennedy Center debut upstairs in the Terrace Theater. Back then he had long brunette ringlets of curls, a sensitive and knowing ear for music, and a crafty way of interlacing modern dance with everything from Bach to country, East Indian raga to punk. And it worked. His young company of ten dancers exuberantly tackled the insouciant steps that were both smart and sly.

Since, Morris and his company have become institutions in the oft-precious modern dance world. He has been back to the Kennedy Center many, many times. Through Saturday, October 29, 2022, the company is ensconced at the Eisenhower with Morris’ newest piece, The Look of Love, an hour-and-change work set to 1960s and ’70s pop icon Burt Bacharach’s hits.

The Look of Love comes on the heels of the company’s last Kennedy Center show in 2019, when it brought Pepperland, an easy-listening, brightly colored homage to the Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. Back in ’85 at his first DC program, the company danced to Vivaldi, Bach, and the Violent Femmes. Nothing was experimental, but it all felt fresh, performed with frisson. Morris’ recent forays into baby boomer songbooks align well with the Broadway retreads of jukebox musicals.

Morris’ followers know well his facility with musicality and his requirement to always use live music. At the Eisenhower Theater, the company music ensemble featured music arranger and long-time MMDG collaborator Ethan Iverson on piano, and gorgeous-voiced Marcy Harriell rendering Bacharach’s songs — with most lyrics by Hal David — in thoughtful jazz renditions, with backup vocals by Clinton Curtis and Blaire Reinhard, joined by Jonathan Finlayson on trumpet, Simon Willson on bass, Vinnie Sperrazza on drums. The ensemble plays in the elevated orchestra pit, and Harriell, glamorous in her bare-shouldered dress, often turns to sing to the dancers on stage.

Raised in Forest Hills, New York, Bacharach, 94, attended the same high school as Simon and Garfunkle and Michael Landon. A child piano student, he favored jazz and later in California studied with mid-century modernist composers Henry Cowell, Bohuslav Martinu, and Darious Milhaud, whom he cites as his greatest influence. But it’s songs like “Alfie,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” and “What the World Needs Now” that defined pop music for the 1960s and ’70s generation. Lively, singable stories of love, longing, loss, and connection, with an occasional shadow tossed in. Morris selected 14 indelible songs from the Bacharach songbook beginning with a jazzy instrumental riff on “Alfie” — surely many heard Dionne Warwick singing in their heads.

On the empty stage a few scattered folding chairs stand — one of the cliches of modern dance is the chair as a prop. It suggests the choreographer needs a device and that’s all that’s available in the rehearsal room.

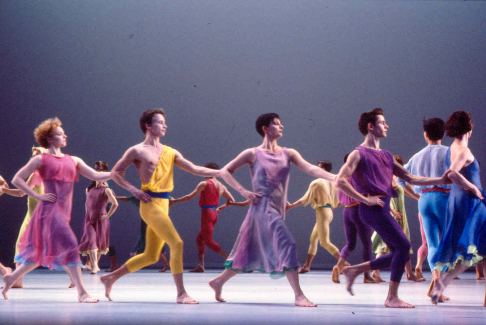

The dancers enter to strains of the feel-good anthem “What the World Needs Now,” clad in sunny pastel tunics, shorts, pants, or dresses color blocked in melon-y orange, lime green, sunny yellow, ochre, and starburst pink. Morris is a master of manipulating simple movement patterns and weaving them into complex spatially shifting phrases. Fans of folk dance will recognize standard footwork featuring stomps, grapevine, and triplet steps in converging and separating lines and circular paths. Another favorite Morris-ism could be termed music visualization, when he has dancers imitate gestures that match the lyrics. It’s like he’s checking to see if we’re listening and watching enough to get his little “Easter eggs.” When the lyrics proclaim: “There are mountains and hillsides enough to climb,” in pairs, one dancer falls as another lifts an arm up — creating the base and peak of the mountain. Later, accompanying “There are sunbeams and moonbeams enough to shine,” one dancer pushes an arm upward with a one-footed hop on sun, the second follows in the other direction on moon as a raised arm indicates a moonbeam.

Next, to “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” on the phrase “What do you get when you kiss a guy? You get enough germs to catch pneumonia,” a little chase ensues before one dancer forces a sneeze on cue at pneumonia. Again and again, Morris has the dancers mimic the lyrics in ways that are easy, obvious, and cute. In my college choreography class this “Mickey Mousing” the music was denigrated as too simplistic. I think it’s become an easy go-to for Morris; it makes the audience feel that they “get” modern dance while letting them feel “smart.”

Morris is at his best at inventing and reshuffling dancers in evolving floor patterns here. With ten dancers moving in, shifting into duos and trios, or playing a soloist against the group his amiable locomotor walks, runs, skips, skitters, and leaps shuffle and reshuffle the landscape on stage. And all this patterning mostly jives with Bacharach’s jazzy, subtle syncopations that add interest to his standard 4/4 common time musicality.

In Harriell’s churchy rendition of “Don’t Make Me Over,” dancers flop and tumble, trying for quirky opposition, then punch a fist in the air. For “Always Something There to Remind Me,” the gesture of choice is pulling on, off, or straightening clothes, as if miming changing an outfit is enough to forget an old lover. For lovers, lost, found, wanted, and wanting are what Bacharach’s lyricist pens so adeptly.

One oddity, “The Blob,” features a dissonant clatter of horns, drums, and piano as the dancers clump together in a pile-up of chairs and limbs against Nicole Pearce’s eerie, blood-red lighting on the backdrop. At first, I thought this creepy start would morph into “What’s New Pussycat?” But, no, a quick Google search told me Bacharach actually composed the film music, and theme song, for the 1958 film The Blob. And that’s what happened: they created a blob of bodies and chairs before moving on.

The evening song cycle concluded with “I Say a Little Prayer,” and here Morris brought the company full circle, returning dancers to the opening circle, as they intersect in a bit of a basket weave. Some now-expected goofy movements — dancers’ arms flapping like wings of graceless angels, as they parse out a pony-like bounce — garner a laugh or two. Then a lexicon of the gestural motifs is recapitulated as the company, two-by-two, one-by-one, makes their way off stage, leaving a lone dancer to exit. The Look of Love ends not on a high note, a bright note, or even a grace note, but on a breathy “Amen.” It’s like a sigh — of relief, of longing, of completion, perhaps. But it feels inadequate, even incomplete.

Throughout, the dancers adeptly work through Morris’ signature paces, but for the most part, they don’t project any particular deep feeling to the movement, the music, or even one another. Sometimes they were just going through their paces rather than reveling in the music visualizations. It’s as if they’re still looking — for inspiration, for ways to fully love and embrace this new work. And it’s a shame because the musicianship of the ensemble should draw these dancers in, but they haven’t fully committed themselves to loving The Look of Love.

This review originally appeared on DC Theater Arts on October 29, 2022, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2022 Lisa Traiger

Sergeant Pepper-mania

Mark Morris Dance Group

Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

November 14-16, 2019

By Lisa Traiger

The choreographer takes his inspiration from music. In his 40-year career as a dancer and dancemaker, he has created more than 150 works. Music has been his constant impetus and companion in his creative process. In performance, he insists on bringing his own music ensemble to accompany the dancers.Mark Morris dances are emphatically watchable, easily digestible, eccentric, and smartly witty. He so proficiently pairs music and dance, costume and set — with a cadre of collaborators — that it’s hard to have a bad night at a Mark Morris Dance Group performance. This is most often due to the deep musical and creative bond he has with long-time musical collaborator Ethan Iverson.

From his gorgeously lyrical masterpiece (L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato ) to the archly sardonic (The Hard Nut, his version of The Nutcracker) to wildly dramatic (Dido and Aeneas), the musically glorious (Falling Down Stairs), the intellectually bracing (“Grand Duo”) and the wicked fun (his very early “Lovey” danced to the Violent Femmes), Morris’s best pieces compel the body to sing, and the movement, steps, formations, phrasing appear as if they were born just for a particular piece of music.

Thus, when he was approached to make a piece to the Beatles, he didn’t play it straight and just set dancers in motion to the sterling and singable recordings of the Fab Four. The commission offered by the City of Liverpool asked for a dance to commemorate the Beatles’ groundbreaking Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 2017. The hour-long work, now on a North American tour with the choreographer’s eponymous Mark Morris Dance Group, is currently on stage at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theatre, where it’s awash in accolades from a boomer audience that can’t get enough of the idea of high-brow dancing to the Beatles.

And the vividly colored, smartly cut early 1960s costumes, thanks to designer Elizabeth Kurtzman, and Johan Henckens’ bronze crinkled mylar set — a nod perhaps to Warhol’s “Silver Clouds,” which populated Merce Cunningham’s “Rainforest” — allow Morris’s clean, simple choreographic choices to shine.

In fact, not once is a recorded vocal from John, Paul, George, or Ringo heard. Iverson has rearranged several of the album’s iconic songs — the title track, “With a Little Help From My Friends,” and “When I’m Sixty-Four” — for an ensemble of six playing sax, trombone, piano, keyboard, percussion, and the electronic space-agey theremin. If you know the album — and anyone born before 1967 must know at least some of it — you’ll hear baritone Clinton Curtis sing a few standards in a mostly non-Beatlesque way. The others? You just have to sing along in your head as the music plays.

On additional sections of the score, Iverson riffs on musical ideas of the period that may or may not have influenced the Beatles. Iverson’s musical addendums peppered into the 13 sections include an adagio; an allegro drawing from an offhand trombone phrase in “Sgt. Pepper”; a scherzo inspired by Glenn Gould, Petula Clark, and a chord progression from the album; and a cadenza that reflects the Beatles’ references to European classical music. They are a nifty way to avoid treacly nostalgia while still honoring the innovative band’s contributions.

The opening notes of the piece strike the final chord on the album, a familiar sound for those who have listened to it. The opening choreography features an unwinding clump of dancers that spirals outward filling the stage with a jumble of bold jelly-bean colors — vibrant yellow, tangerine, aquamarine, grape, and hot pink tailored sharply into mod slacks, skirts, turtle necks, and jackets. A little skip-hop step with the arms carefully placed reflects a walker’s gait — the walk across Abbey Road maybe? The company of 15, plus five apprentices, imbues these introductory phrases with a heightened naturalness as their legs pierce the air, arms slicing, palms outward, opened to the audience.

After that initial unwinding moment, the “Magna Carta” section introduces historic figures who make an appearance on the colorfully iconic album cover — from Albert Einstein to Marilyn Monroe to bluesman Wilbur Scoville to boxer Sonny Liston — at each name, a dancer jogs in and takes a pose suggestive of the personality of the figure.

Morris cares little for traditional virtuosic tricks. In fact, his technique is closer to that of founding mother of modern dance Isadora Duncan’s runs, skips, jumps, and hops than the codified virtuosity of either ballet or mid-century moderns like Martha Graham and Paul Taylor. His early training in Balkan folk dances also shows in circle formations, hand-holding pairs, and short lines of dancers, linked and maneuvering in unison.

In Morris’s works a sense of humanity prevails. Yet, the company has changed over time, from a mixed-bag bunch of highly proficient dancers of various heights, body types and backgrounds, to today’s company, which is not necessarily less diverse, but its members are far more similar physically. Everyone is trim, with long legs and an aesthetically pleasing dancerly quality, you can see their ballet backgrounds in the less weighty earthy attack. It makes for a more uniform, although far less interesting looking company. Morris still prizes dancers who are fully themselves on stage and who strive to emulate the human condition in performance.

The evening — like much of Morris’s choreography — plays astutely with theme and variation. Morris enjoys having dancers hold hands, link arms and march or walk in mini regimental rows, four abreast, a nod to the Fab Four. In a series of lovely adagios, one partner in a male-female or same-sex couple lifts the other, whose legs stick straight down in a modest straddle, toes pointed. It’s a simple but distinctive motif. Other repeated phrases include some small traveling skips, skitters and leaps, a big bursting jump with arched backs — cheerleader-y — and some simple turn sequences. Morris shuffles and reshuffles these motifs in ways that make the viewer feel smart — “Oh, yes, I saw that before. I see what you’re doing here” — using a different structure, formation, number of dancers or even sequential or canonic counts.

Morris also winks at the psychedelic era by putting his dancers in mirrored sunglasses on occasion — those “kaleidoscope eyes” from “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” and with some moments late in the work, he lets them loose for free form movement. But the work is conscientiously structured, not improvised. Late in the piece, as “Penny Lane” — not on the album, although originally written for “Sgt. Pepper’s” — plays, the dancers enact an old-fashioned pantomime to the lyrics — getting into a barber’s chair, driving a car, offering a queenly smile and wave, etc. Audiences enjoy the humor and again see the Morris style at work. Other references he throws in might be less obvious such as the mudra, or Indian hand gesture of thumbs up used in the Indian dance form bharata natyam. But for Morris it reflects his love for and study of Indian classical dance. There are plenty of other “Easter eggs” in any Morris work; Pepperland is no exception.

Interestingly, as tuneful and musically interesting as Pepperland is, especially if you read the composer’s program notes, the piece doesn’t come close to a Morris masterwork. The choreographer must love the music completely to attain such a sublime aesthetic level. He’s created dances to Mozart, Britten, Purcell, Bach, Prokofiev, as well as country music, punk rock, Indian ragas and Azerbaijani mugham songs, to name a very few, so a bit of Beatles is no stretch for his rangy musical tastes. But Pepperland simply doesn’t sing in the way his best works can. It doesn’t feel like Morris is all-in. Choreographically, the work is as adept as any of his most recent, showcasing the strengths and talents of his well-honed company, his unparalleled skill in structuring dances that move easily. While it’s unfair to expect a masterpiece every season, Pepperland feels more like an assignment completed: Liverpool wanted a Beatles ballet? Well, Morris went ahead and delivered one.

Finally, for all the bright colors and the tuneful Beatles songs, the oft peppy, upbeat dancing, the whirl of shifting musical and costume colors, Pepperland emanates a surprisingly sober, even somber, tone behind those mirrored sunglasses the dancers wear. The initial opening clump, turns back in on itself at the end, the dancers collapsed, exhausted, overcome as the music rumbles. When asked why he had sad sections in the piece during the post-show discussion on opening night, Morris was, as usual, sharply glib: “Well, it’s a fucking sad world, that’s why.” Then he waved goodnight, tossed his scarf over his shoulder and swanned off.

Photos courtesy The Kennedy Center, top by Gareth Jones, middle by Mat Hayward,

bottom by Robbie Jack.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2019 Lisa Traiger

Tapestry

Layla and Majnun

Mark Morris Dance Group and The Silkroad Ensemble

Featuring Alim Qasimov and Fargana Qasimova

Kennedy Center Opera House

Washington, D.C.

March 22, 2018

By Lisa Traiger

A tapestry of poetry, chant, music and dance drawn from a swath of the ancient Silk Road has provided vivid inspiration for influential choreographer Mark Morris. His re-envisioning of Layla and Majnun, the ancient tale of star-crossed lovers with roots in Persia, Azerbaijan and other Silk Road locales, an ancient trade root which stretch across Asia from Japan to the Mediterranean Sea, fills a riveting 65 minutes. Morris’s acclaimed and beloved dance troupe has made a return Kennedy Center visit, and on opening night March 22 the full Opera House indicated that his choreographic vision continues to astound — and break down cultural barriers.

Modern dance and ancient Azerbaijani music? Yes, please, it works on multiple levels.

This cross-cultural collaboration, which premiered in 2016 at Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall, knitted together celebrity cellist Yo-Yo Ma’s brainchild, the Silkroad Project, with renowned Azerbaijani father and daughter mugham singers Alim Qasimov and Fargana Qasimova, and Morris’s articulate dancers retelling a poetic tale of forbidden love. It’s no wonder the marketing material touted the work’s similarity to “Romeo and Juliet,” though the original tale dates back to the 12th century, about four centuries before Shakespeare penned his own star-crossed-lover tale of woe and tragedy.

Interestingly, the eight Silkroad musicians — beautifully clad in bold sunflower yellow batik prints — and the Qasimovs are placed right in the center of the stage on elevated platforms. In the five short acts the dancers maneuver around them, up and down the stepped risers performing on various levels behind the musicians or close to the lip of the stage in front of them. It’s a subtle nod to the importance Morris gives to the music and it’s also an acknowledgement that this East-West meeting of music and dance culture is not appropriating, it is emphasizing the ancient traditional singing an instrumentation. And with the late Howard Hodgkin’s gorgeous costumes evoking Central Asia, inspired by miniature paintings from Azerbaijan, and a striking backdrop featuring oversized brush strokes in deep green and strong orange, the work is more than dance, music or opera. I would reach back to Richard Wagner and call it gesamtkunstwerk — a mouthful that means a “total work of art” or a work that synthesizes allied arts — music, dance, theater, painting, poetry — into a singular piece. In dance, during the Ballets Russes era, dancer-turned-choreographer Michel Fokine also promoted this concept. Morris gently brings it into the 21st century.

For movement material, Morris delves deep into his early dance background as a folk dancer — think Greek, Balkan, Serbian, Macedonian — during his teen years and imbues the choreography with a crystalline simplicity that relies on concise arm gestures that stretch, reach and curve with a fine sense of plastique. His footwork, too, is spare, based on natural locomotor movements: walking, stepping, lunging, and, during a celebratory scene, hops, two-footed jumps and tiny mincing steps that could be balletic bourres. He uses the ballet arabesque shape as a decorative gesture akin to the curvilinear lines seen in Arabic calligraphy and art. Instead of a static geometric pose or pause, Morris’s arabesques flow with ease from a balance on one leg, the other lifted behind, into a deep lunge forward in continuous motion, like a calligrapher’s pen tracing elegant script.

The story unfurls in five brief acts, and in each a different pair of dancers play the doomed lovers, a doubling technique that Morris has used in previous works, most notably his 1989 Dido and Aeneas, where he split the central character into two roles — Dido and the destroyer — which he himself played at once. While the dancers are clad uniformly, the women in long tangerine-colored dresses, the men in sea blue silk tunics and white pants, they represent the universality and unity of the community. Out of the many, Leyla and Majnun are each distinguished by a scarf that gets passed on from act to act. As the acts proceed, from the first “Love and Separation” to “The Parents’ Disapproval” to “Sorrow and Despair,” “Layla’s Unwanted Wedding” to the final “The Lovers’ Demise,” the interchangeable couples seamlessly transform from the corps to the lead soloists. This sharing of the lead lovers lends an added sense of universality to the heartbreaking tale drawn from a Persian poem by Nezami Ganjawl, which, too, takes inspiration from older sources on the trade routes. Forbidden love, it seems, has a long and fraught history that continues to capture our hearts and catch in our throats.

The ancient narrative unspools to the plaintive chants of Qasimov and Qasimova and as their voices trill and cant, cry and tremble, you can hear the unrequited desire, the everlasting longing, the pain of separation and the inevitable choice to choose a poignantly beautiful death over a miserable loveless life. Structurally, Morris follows the musical and poetic scores in the work and remains respectful of the Muslim culture from which it derives. The dancers’ costumes are modest, though the women’s hair does flow freely — in the spirit of young love perhaps? — and there are gendered spaces, though Morris’s democratic ethos means that even when men and women are often separated by the center-stage musicians and the risers, they perform the same gestures and steps, in unison and canon.

Morris consciously nods to dance genres linked to the Silk Road — a paddle turn, one palm up and one down, recalls whirling dervishes and he lets the dancers recline on the floor, like ancient Greeks leaning on an elbow at a banquet. The livelier dances resemble pairs of folk dancers with quick little runs, shoulders ticking forward and back, or arms slung across shoulders as short lines of men travel in grapevines like so many central European dances. I also noted a reverence for early 20th century dance modernists — Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis in particular — who both sought inspiration from the art and culture of the Silk Road. In Morris, you see it in snaking arms, wide body tilts to the side, and crooked elbows and knees emphasizing angularity rather than smoothly pleasing body positions — think a sensual S-curve drawn from Indian dance, or a fleet-footed sculpture of Mercury, his lifted leg cocked behind him, ready for flight.

Most instructive of the Muslim roots of the story, Morris ensures that the longing lovers Layla and Majnun don’t touch until the end. And the momentary lingering of a hand on a cheek proves more effective and pure than a Hollywoodesque full-on embrace and smooch. There’s a lovely section where he, surrounds his partner with an open armed hug, but their bodies never meet, and then she returns the gesture, as the motif continues, again and again. These moments of gendered spaces meeting with the utmost restraint reveal the power in our over-sexualized society in holding back.

That, too, is the beauty of Morris’s choreographic vision in Layla and Majnun — that earthly love, while enticing, can only attain divinity when body, soul and spirit are sacrificed for eternal love. It’s a story that continues to live across cultures and centuries — conquering intolerance with love.

This piece was originally published on dcmetrotheaterarts.com, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

Photos by Susana Millman, courtesy Kennedy Center.

Top: dancers: Lesley Garrison and Durell R. Comedy in Layla and Majnun

Bottom: Billy Smith and Nicole Sabella, Aaron Loux and Rita Donahue, Lesley Garrison and Durell R. Comedy

Published March 23, 2018

© 2018 Lisa Traiger

video: Mark Morris on the making of “Layla and Majnun” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y7qldzZcuS4

A Personal Best: Dance Watching in 2012

Like many, my 2012 dance year began with an ending: Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Much was written on the closure of this 20th-century American treasure after more than 50 years, especially its final performance events on the days leading up to New Year’s Eve 2012. At the penultimate performance on December 30, the dancers shone, carving swaths of movement from thin air in the hazy pools of light spilling onto raised platform stages in the cavernous Park Avenue Armory space. A piercing trumpet call emanated from the rafters heralding the start of this one-of-a-kind evening. Pillowy, cloud-like installations floated above in near darkness. Throughout, snippets of Cunningham choreography – I saw “Crises,” “Doubles” and maybe “Points in Space” – came and went, moving images played for the last time, while audience members sat on folding chairs, observed from risers or meandered through the space, taking care not to step on the carpeted runways that the dancers used to travel from stage to stage.

I found it refreshing to get so close to the dancers after years of partaking of the Cunningham company in theatrical spaces, for me most commonly the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. Here the dancers became human, sweat beads forming on their backs, breathe elevated, hair matting down toward the end of the evening. Duets, trios, groups formed and dissolved in that coolly unemotive Cunningham fashion, with alacrity they would step off the stage and rest and reset themselves before coming back on again for another round of the complex alphabet of Cunningham bends, pelvic tilts, lunges, passes, springs, jumps and playful leaps. While the dancers energy surged, I felt time was growing short. The end near. I soon found myself on a riser standing directly above and behind music director Takehisa Kosugi who at the keyboard conducted the ensemble and held an digital stop watch. Journalists traditionally end their articles with – 30 –. Here, momentarily I got distracted with the numbers: 41’38”, 41’39”, 41’40”, 41’41” … And then within a minute Kosugi nodded and squeezed his thumb: at 42’40”. An ending stark, poignant, and by the book.

In January, the Mariinsky Ballet’s “Les Saisons Russes” program was an eye opener on many levels. The work of Ballets Russes that stunned Paris then the world from 1909 through 1914 under the astute and market-savvy vision of Serge Diaghilev, remains incomparable for audiences today. The triple bill of Mikel Fokine works wows with its saturated colors and vividly wrought choreographic statements, impeccably executed by Mariinsky’s stable of well-trained dancers. These three ballets – “Chopiniana” from 1908, and “The Firebird” and “Scheherazade” from 1910 – continue to pack a powerful punch, a century after their creation. The subtle Romanticism distilled with elan by the Mariinsky corps de ballet — from the perfection etched into their curved arms and slightly tilted heads, their epaulment unparalleled — makes one pine for a bygone Romantic era that likely never actually attained this level of technical grace and precision. With “Firebird,” the Russian folktale elaborately retold in dance, drama and vibrantly outlandish costumes, the flamboyant folk characters were part ‘80s rock stars, part science fiction film creatures. Finally, the bombast and melodrama of the Arabian Nights rendered through Fokine’s version of “Schererazade” danced as if on steroids provided outsized exoticism, with more sequined costumes, scimtars and false facial hair and the soap operatic performances to suit the pompous grandeur of the Rimsky-Korsakov score. Surely Diaghilev would have approved.

Also in January, Mark Morris Dance Group returned to the Kennedy Center Opera House with its brilliant L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, danced with humanity and glee to Handel’s oratorio, itself based on 17th-century pastoral poem by John Milton and the watercolor illustrations of William Blake. Morris – and Milton, Blake and Handel – each strove for a utopian ideal. This work draws together its disparate parts into one of the great dance works of the 20th century. Enough has been spoken and written about this glorious rendering in music, with the full-voiced Washington Bach Consort Chorus, wildly overblown and softly understated dancing from an expanded company of 24 elegant and spirited movers, and set design – vivid washes of color and light in ranging from flourish of springtime hues to fading fall colors — by Adrianne Lobel. L’Allegro was produced abroad, in 1988 when Morris and his company were in residence at the Theatre Royale de la Monnaie in Belgium, at a time and a place when dance received unprecedented financial and artistic support. I was struck by the open democratic feeling of the dancers, each on equal footing, soloists melding into groups, humorous bits shifting to serious interludes, no dancer stands out individually. For Morris, whose roots date back to folk dance, the community, the group, the natural feeling of people dancing together is valued above the singularity of solo dancing. It’s democracy – small d – at its best. Watching the work again this year, as dance companies large and small balance at the edge of a seemingly perpetual fiscal cliff, was a reminder of how small and cloistered American modern dance has become. We have few choreographers with the resources and the daring to attempt the bold and brash statements that Morris harnessed in L’Allegro.

Another company that leaves everything on stage but in an entirely different vein is Tel Aviv’s Batsheva Dance Company, which I caught at Brooklyn Academy of Music in March. Hora, an evening-length study in gamesmanship and internalized worlds made visible was created by company artistic director (and current world-renowned dance icon) Ohad Naharin. With his facetiously named Gaga movement language, dancers attained heightened sensitivity, not dissimilar to the work butoh masters and post-modernist strove for in earlier decades. And yet the steely technical accomplishment and steadfast allegiances to dancing in the moment that Gaga pulls from its best proponents makes Batsheva among the world’s most prized and praised contemporary dance companies. At BAM, the 60 minute work with its saturated colors and pools of shifting lighting by Avi Yona Bueno and music arranged by Isao Tomita featuring snippets from Wagner, Strauss, Debussy and Mussorgsky offers a smorgasbord of familiarity as the dancers parse oddly shaped lunges with hips askew, pelvises tucked under, ribs thrust forward and heads cocked just so. Odd and awkward, yet athletic and graceful, and undeniably daring Naharin mines his Batsheva dancers for quirks that become accepted as fresh 21st century bodily configurations. Though named Hora, the work has nothing whatsoever to do with the ubiquitous Jewish circle dance, yet after an evening with Batsheva, it’s hard not to feel like celebrating.

Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz in “Necessary Weather,” with lighting by Jennifer Tipton, photo: Stephanie Berger

In April, Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz glimmered in “Necessary Weather,” a subtle tour de force filled with small moments of great and profound drama and even, unexpectedly, a smile or two. The glide of a foot, cock of a head, even a raised eyebrow or tip of a hat from Rudner and Reitz resonated beneath the glow of Jennifer Tipton’s lighting, which in American Dance Institute’s Rockville studio theater, performed a choreography of its own glowing, fading, saturating and shimmering.

Also at ADI in May, Tzveta Kassabova created a rarified world – of the daily-ness of life and the outdoors. By bringing nature inside and onto the stage, which was strewn with leaves, decorated with lawn furniture, and, in a coup de theatre, a mud puddle and a rain storm. Her evening-length and richly rendered Left of Green, Fall, choreographed on a wide-ranging cast of 16 child and adult dancers and movers, featured sound design and original music with a folk-ish tinge by Steve Wanna. The work tugs at the outer corners of thought with its intermingling of hyper-real and imagined worlds. The senses also come into play: the smell of drying leaves, the crackly crunch they make beneath one’s feet and the moist-wet smell of fall is startling, particularly occurring indoors on a sunny May afternoon. Kassabova, with her flounce of bouncy curls and angular, sharp-cornered body, dances with a laser-like intensity. She’s ready to play, allowing the sounds and sights of children in a park, sometimes among themselves, other times with adults. She’s also game to show off awkwardness: turned in feet, sharp corners of elbows, hunched shoulders and flat-footed balances – providing refreshing lessons that beauty is indeed present in the most ordinary and the most natural ways the body moves.

The Paris Opera Ballet’s July stop at the Kennedy Center Opera House brought an impeccable rendering of one of the pinnacles of Romantic ballet: Giselle. And should one expect anything less than perfection when the program credits list the number of performances of this ballet by the company? On July 5, 2012, I saw the “760th performance by the Paris Opera Ballet and the 206th performance of this production,” one with choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot dating from 1841, transmitted by Marius Petipa in 1887 and adapted by Patrice Bart and Eugene Polyakov in 1991. Two days later it was 763. The POB still uses the 1924 set and costume designs of the great Alexandre Benois, adding further authenticity to the work. But nothing about this production is museum material. POB continues to breathe life into its Giselle.

Aside from making a pilgrimage to the imaginary graveside of the tragic maiden dancer two-timed by her admirer, it’s hard to find a more accurate and handsome production of this ballet masterpiece. Aurelie Dupont was a thoughtful and sophisticated Giselle, care and technical virtuosity evident in her performance, while her Albrecht, Mathieu Ganio, played his Romantic hero for grandeur. While the 40-something husband and wife duo of Nicholas Le Riche and Clairemarie Osta on paper make an unlikely Albrecht and Giselle, in reality their heartfelt performances were so intensely and genuinely realized at the Saturday matinee that they felt as youthful as Giselles and Albrechts a generation younger.

The production is as close to perfection on so many levels that one might ever find in a ballet, starting with a corps de ballet that danced singularly, breathing as one unit, most particularly in the act II graveside scene. The mime passages, too, were truly beautiful, works of expressive artistry many that in most companies, particularly the American ones, are dropped or given short shrift. Here the tradition remains that mime is integral to the choreography, not an afterthought but a moment of import. Most interesting was a (new to me) mime sequence by Giselle’s mother about the origins of her daughter’s affliction and how she will most definitely die (hands in fists, crossed at the wrists, held low at the chest). Later when the Wilis dance in act II, it becomes abundantly clear why their arms are crossed, though delicately, their hands relaxed: they’re the walking dead, zombies, if you will, of another era. Another unforgettable moment in POBs Giselle, is its use of tableaux at then ending moment of each act. Each act ends in a moment of frozen stillness – act one of course with Giselle’s death, act two with the resurrection of Albrecht. Each of these is captured in a stage picture, then the curtain dropped and rose again – and there the dancers stood, still posed in character. Stunning and memorable.

Each year in August the Karmiel Dance Festival swallows up the small northern Israeli city of Karmiel as upwards of reportedly 250,000 folk and professional dancers swarm the city for three days and nights of dance. From large-scale performances in an outdoor amphitheater to professional and semi-professional and student companies performing in the municipal auditorium and in local gymnasiums and schools to folk dance sessions on the city’s six tennis courts, Karmiel is awash in dance. I caught companies ranging from the silky beauty of Guangdong Modern Dance Company from China’s Guangzhou province, France’s Ballet de Opera Metz under the direction of Patrick Salliot, the youthful and vivacious CIA Brasileira De Ballet, where artistic director Jorge Texeira seeks out his youthful dance protégés from the streets and barrios of some of the poorest neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, Terrence Orr’s Pittsburgh Ballet Theater, and Israel’s Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, directed by Rami Be’er in a program of new works by young dancemakers. Maybe not the best that I saw, but the unforgettable oddity of the three-day festival was the headlining company, billed as the Cossack National Dance Troupe from Russia. In the grand folk dance tradition of the great Moiseyev company of Russia, these dancers, musicians and singers – numbering 60 strong – let the sparks fly, literally. With breathtaking sword play where white hot sparks truly did fly from the swords, to astounding acrobatic feats and graceful, feminine dances featuring smoothness, precision and delicate footwork parsed out in heeled character boots, the troupe was a hit. Few in the appreciative Israeli crowd – many of whom sang along to the old Russian folk songs buying into a mythic pastoral vision of the Cossack warriors – seemed aware of the irony of an audience of predominantly Israeli Jews heartily applauding a show titled “The Cossacks Are Coming!” The last time Jews were heard to say “The Cossacks are coming,” things didn’t turn out so well.

In September, Dance Place was fortunate to book one of the State Department’s CenterStage touring troupes at the top of its season. Nan Jombang, a one-of-a-kind family of dancers from the Indonesian island of Sumatra, provided a remarkable and moving evening in its North American premiere. Rantau Berbisik or “Whisperings of Exile” begins with a siren call, a female shriek that’s an alarm and cry of pain, that begins a journey of unexpected images. Ery Mefri, a dancer from Padang, on the western coast of Sumatra, has created a surprisingly original dance culture drawing from traditional tribal rituals, martial arts – randai and pencak silak – captivating chants and unusual body percussion techniques. But most unique about Mefri’s artistic project, and the company he founded in 1983, is that it is truly a family affair: the five dancers are his wife and children. The live, sleep, eat and work together daily in intense isolation crafting dances of elemental power and uncommon dynamism through an intensely intimate process.

The work features a trio of gloriously powerful women who exhibit strength of body and will in the earthbound manner they dive into movement, oozing into deep plie like squats and then pounding the taut canvas of their stretched red pants like drummers. Moments later they spring forth from deep lunges, pouncing then retreating, only to strike out again. The hour-long work is filled with mystery and mundanity: dancers carry plates and cups back and forth from a tea cart, rattling the china in percussive polyrhythms, and one woman sits in a chair and keens, rocking and hugging herself for an inconsolable loss. Later the women pass and stack plates around a wooden table with an urgency and assembly-line precision that brings new meaning to the term woman’s work. The one thin boy/man in the group attacks and retreats with preternatural grace, sometimes part of this female-dominated social structure, other times apart – an outcast or loner. And throughout amid the bustle, the urgent calls, the unmitigated pain and sense of loss, there remains a stunning impression of yearning, of hope. The ancient rituals of home and hearth, of work and rest, of group and individual it seems are drawn from a language and way of life that Mefri sees disappearing. Quickly evident in this riveting evening is how Mefri and his family can communicate so deeply to the heart and soul in ways that strike at the core, of unspoken truths about family, community and cultural continuity and conveyance.

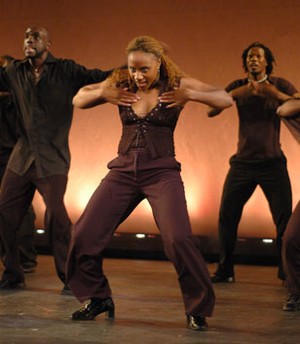

One final note of continuity and cultural conveyance was struck resoundingly in December with Chicago Human Rhythm Project’s “Juba: Masters of Tap and Percussive Dance” at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. While the program was long on youth and short on masters – an indication that we’ve reached the end our last generation of true tap masters — Dianne “Lady Di” Walker represented the early tap revival providing the link to old time rhythm tap of the early and mid-20th century. The program, emceed and curated by Lane Alexander of CHRP, brought together a bevy of youthful dance companies, among them Michelle Dorrance’s Dorrance Dance with an interesting excerpt for two barefoot modern dancers and a tapper. D.C. favorite Step Afrika! brought down the first act curtain with its heart-raising rhythms and body slapping percussion. And, closing out the evening, Walker served up “Softly As the Morning Sunrise,” a number as smooth and bubbly as glass of Cristal, her footwork as fast as hummingbird wings, her physics-defying feet emitting more sounds than the eye could see. This full evening of tap also included Derik Grant, Sam Weber, and younger pros Jason Janas, Chris Broughton, Connor Kelley, Jumaane Taylor, Joseph Monroe Webb and Kyle Wildner. The evening with its teen and college aged dancers sounded a note that tap will continue to be a force to reckon with in the 21st century. That it occurred on a main stage at the Kennedy Center was – still – a rarity. Let’s hope the success of this evening will lead to more forays into vernacular and percussive dance forms at the nation’s performing arts center. The clusters of tap fans young and old gathered in the lobby after the show couldn’t bear to leave. If they had thrown down a wooden tap floor on the red carpeting, no doubt folks would have stayed for another hour of tap challenges right there in the lobby.

***

And I can’t forget a final, very personal experience. During the annual Kennedy Center run of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in February, I found myself pulled from my aisle seat to join the dancers onstage in Ohad Naharin’s “Minus 16,” which the company had just added to its repertory in late 2011. Clad in slim fitting business suits and stark white shirts, the dancers make their way to the lip of the stage and stare. The next thing you know, they’re stalking the aisles, climbing over seats, crawling across laps to bring up randomly selected members of the audience. The sequence is fascinating – a mix of the mundane, the ridiculous and the dancerly – inviting in the human element as these god-like dancers canoodle, slow dance, cha-cha and indulge their new-found partners. Soon they corral the group, circle, and in ones and twos the dancers begin to lead the participants off stage, leaving just one – most frequently a woman – standing in the embrace of her partner as the others hug themselves in a smug slow dance. On cue the dancers fall. The woman remains alone, in the spotlight. Frequently aghast, embarrassed, she slinks away.

Dreamlike is the best way I can describe the experience. Audience members seem to be selected according to a particular color, most frequently red judging from the previous times I’ve seen the work. As a “winter” on the color chart, I, of course, frequently wear red from my beret to my purse to a closet full of sweaters and blouses. When the dancers lined up, I felt one made eye contact with me right away. I didn’t avert my gaze and I thought that I could be chosen. But as they came into the audience, he passed me by and I exhaled slightly, relieved not to be selected. The stage re-filled with dancers and their unwitting partners as I watched. Suddenly, the same dancer who caught my eye was at my side beckoning, pulling me from my seat. My hand in his I followed him down the dark aisle and up the stairs. There the music changed frequently from kitschy ‘60s pop to rumba, cha cha, and tango – all recognizably familiar, a Naharin trait. Yet the choreographer definitely wants to keep the novices off guard, which is disconcerting because there are moments when the dancers are completely with you and you feel comfortably in their care, then they leave you to your own devices and all bets are off.

I realized quickly that I had to focus fully on my partner and not get distracted by what others on stage or in the audience were doing. We maintained eye contact throughout and went through a bevy of pop-ish dances: I recall bouncing, lunging, throwing in a bump or two and a great tango – wow, what a lead. Then they mixed things up, pushing all the civilians into a circle then a clump before reshuffling things. Somehow I came out with a new partner and things really heated up as I followed him and he me. I felt my old contact skills tingling back to life as I tried to give as good as he gave. He dipped me and I suspect that when he felt I gave in to it, he realized he could take me further. I don’t know how, but I found myself lifted above his head in what felt like a press. As he turned, I thought I might as well take advantage of this. I’m never going to be in the arms of an Ailey dancer again. I put one leg in passe, straightened the other, threw my head back and lifted my sternum, while keeping one hand on my head so my beret wouldn’t fly. He likely only made two or three rotations, but in my mind it felt like a carnival carousel: incredible. Back on earth with my feet on solid footing, he tangoed and embraced me. I knew what was coming. The slow dance when they lead partners off stage. I realized I might was well give in to the moment, I melted into his embrace and we swayed. Two bodies as one. Eyes closed. I momentarily opened them when I sensed the stage emptying. The only words spoken between us are when I said, “uh oh.” He squeezed me and then dropped to the floor in an X with the remaining Ailey dancers. There I was. Alone. Center stage in the Kennedy Center Opera House. I have been seeing performances there since I was a child in 1970s. I had seconds to decide what I was going to do. “%^&#) it,” I said to myself. “I’m standing here in the Opera House with 2,500 people looking at me. I’m going to take my bow.” I moved my leg into B+, opened my arms with a flourish, dropped my head and shoulders and rose, relishing the moment for all it was worth. Seconds later, the audience roared. I was stunned. I made my way gingerly off stage, still blinded by the spotlights as I fumbled up the aisle to find my seat.

Dreamlike. Throughout I knew this was something I would want to relish and remember and tried to find markers for while maintaining the presence of the moment. I was able to find out who the dancers were (yes, there were two) who partnered me. But I believe that Naharin wants the mystery to remain both for the onlookers and the participants. At intermission people were asking if I was a “plant,” insisting that I must have known what to do in advance. But, no, Naharin wants that indeterminacy, that edginess, that moment of frisson, when the audience realizes that with folks just like them on stage, all bets are off on what could happen. While we often attend dance performances to see heightened, better, more beautiful and more physically fit and skilled versions of ourselves (one of the reasons, I think, that we also watch football, basketball and the like), there’s something about seeing someone just like you or me up on stage. If the middle aged mom who needs to get the kids off to school then go to work the next morning can have such a rarified experience then maybe, just maybe, the rest of us can rediscover something fresh, untried, daring, out of sorts, amid the banality of our everyday lives. In this brief segment – and I couldn’t tell you how long it lasted, but I’m sure not more than five minutes at most – Naharin, through the heightened skill and beauty of professional dancers, offers escape from the ordinary. Audiences live through it vicariously by seeing one of their own up there on stage. For me the experience was unforgetable.

© 2012 Lisa Traiger

Published December 30, 2012

Morsels From Morris

Mark Morris Dance Group

Center for the Arts George Mason University

Fairfax, Virginia

February 4, 2011

By Lisa Traiger

© 2011 Lisa Traiger

Published February 7, 2011

![Morris a14Oct_BS20453[1] Morris a14Oct_BS20453[1]](https://dcdancewatcher.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/6a00e39823a90188330147e2626d38970b-320wi.jpg?w=300) At Morris Dance Group’s nearly annual stopover at George Mason University’s Center for the Arts, the company served up plenty of tasty morsels, but little in the way of a substantial main course on a program that featured two newer works and a pair of vintage dances. A long-time favorite at the Northern Virginia college campus, where two dance professors –- Susan Shields and Dan Joyce — claim Mark Morris provenance on their resumes, Morris’s troupe has a regular following there. Even so, the evening felt less like an occasion than a mandatory stop in the D.C. suburbs of Fairfax.

At Morris Dance Group’s nearly annual stopover at George Mason University’s Center for the Arts, the company served up plenty of tasty morsels, but little in the way of a substantial main course on a program that featured two newer works and a pair of vintage dances. A long-time favorite at the Northern Virginia college campus, where two dance professors –- Susan Shields and Dan Joyce — claim Mark Morris provenance on their resumes, Morris’s troupe has a regular following there. Even so, the evening felt less like an occasion than a mandatory stop in the D.C. suburbs of Fairfax.

Of the program’s newer works, “Excursions” is a tricky little piece: deceptively simple, its six dancers play against one another in groups and breakaway solo moments, interlocking in chains and pairing or tripling up. With Samuel Barber’s “Excursions for the Piano” as the musical girder supporting and launching the dancers into eddies of skips, gallops, crawls, and even a butt-bumping scoot across the floor, the piece frolics and meanders, sometimes with loopy clownishness, other times with a darker more subdued cast. Gestural motifs suggest a homespun, conversational air, especially when the dancers lift their fists and to shake them at no one in particular like they are damning someone in anger. The four piano pieces, played with brio by Colin Fowler, appear in reverse order, beginning with four and counting backward to one – another structural trick Morris pulls out of his sleeve. He punctuates easy-going dancers’ strides with hip shimmies, table-top arms palms down, and casual leaps and hops that play the group against an individual. The work unfolds like a picaresque, as the group journeys it seems over, under, through and around the bare stage, their paths seem to demarcate fences, hills, valleys, roads and cul de sacs where they might meander and stop for a moment before forging ahead.

![Morris 2 14Oct_BS20457[1] Morris 2 14Oct_BS20457[1]](https://dcdancewatcher.files.wordpress.com/2011/03/6a00e39823a90188330147e262731b970b.jpg?w=300) “Petrichor,” the program’s newest work, premiered just this past fall in Boston, and features a live performance of Heitor Villa-Lobos’s String Quartet No. 2. The eight woman, draped in Elizabeth Kurtzman’s chiffon baby-doll length shifts in shades of fuchsia and lavender over sleek, shiny biker suits, recall Isadorables in their airy, tossed off breathy but never breathless skitters, skips and leaps across the stage. Recalling Grecian antiquities in their poses -– a head cocked just so, fingers and hands shaped to emphasize a curve of a cheek or a finely etched chin –- “Petrichor” pays unassuming tribute to the founding mother of modern dance without forcing the issue. Why not return to ideas and concepts dances’ early moderns? That’s a lesson Morris has learned and assimilated well over the years in works that reflect without mimicry or irony their roots in the now oft-overlooked traditions of Denishawn, Humphrey-Weidman and Duncan. The movement sweeps along, the eight women motivated by their soul centers, their arms butterflying in waves, their bodies soaring, their hands sparking like fireflies blinking in the darkness. It’s a lovely, too sweetly realized confection.

“Petrichor,” the program’s newest work, premiered just this past fall in Boston, and features a live performance of Heitor Villa-Lobos’s String Quartet No. 2. The eight woman, draped in Elizabeth Kurtzman’s chiffon baby-doll length shifts in shades of fuchsia and lavender over sleek, shiny biker suits, recall Isadorables in their airy, tossed off breathy but never breathless skitters, skips and leaps across the stage. Recalling Grecian antiquities in their poses -– a head cocked just so, fingers and hands shaped to emphasize a curve of a cheek or a finely etched chin –- “Petrichor” pays unassuming tribute to the founding mother of modern dance without forcing the issue. Why not return to ideas and concepts dances’ early moderns? That’s a lesson Morris has learned and assimilated well over the years in works that reflect without mimicry or irony their roots in the now oft-overlooked traditions of Denishawn, Humphrey-Weidman and Duncan. The movement sweeps along, the eight women motivated by their soul centers, their arms butterflying in waves, their bodies soaring, their hands sparking like fireflies blinking in the darkness. It’s a lovely, too sweetly realized confection.

In “Silhouettes,” a handsome duet danced on Friday by broad-chested Domingo Estrada, Jr., and slim Noah Vinson, the two shared a single pair of pajamas, one top, one bottom (a homoerotic insider joke from Morris?). The barefoot petite allegro variations could easily have been borrowed from ballet class, likewise the balance-challenging leg lifts or developes. The evening closed with the Texas-style two-step romp, “Going Away Party,” featuring the twangy cowboy blues of Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys. Clad in Christine Van Loon’s cowboy boots, tight jeans or cowgirl skirts and fringed or embroidered Western shirts, the dancers cavort in gallops, partnering up save for odd-man-out William Smith in Morris’s original role. Playing with the quirky country lyrics, the choreography mimics but doesn’t Mickey Mouse the words with a facetious wink: “arms keep reaching for you …” underscores the partners thrusting their pelvises toward each other -– evidence of Morris’s wicked sense of humor. Pre-“Brokeback Mountain,” “Going Away Party” slyly suggests malleable boundaries between and among the three women and four men, who couple up with sometimes longing looks over their shoulders to another. An amusing evening closer, the work, like those danced before, didn’t provide a meaty centerpiece in the program. That left this viewer longing for a heartier sampling from Morris’s more substantial works –- a “Grand Duo,” “Falling Down Stairs” or “Gloria” — to provide more than just tidbits, but a main course to savor fully.

Photos: “Petrichor” by Mark Morris, courtesy Mark Morris Dance Group/Bryan Snyder

Published February 7, 2011

© 2011 Lisa Traiger

leave a comment