2015: A Look Back

For reasons that continue to surprise me, 2015 was a relatively light dance-going year for me. That said, I managed to take in nearly a top ten of memorable, exceptional or challenging performances over the past 12 months.

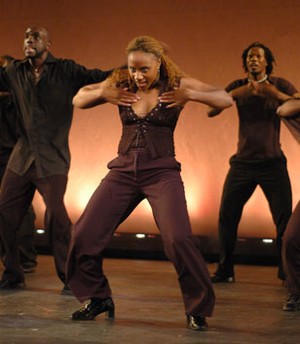

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, on its annual February Kennedy Center Opera House visit, brought a program of politically relevant works that culminated, as always, in the inspirational paean to the African-American experience, “Revelations.” Up first, though, was the restless “Uprising,” an athletic men’s piece that draws out the animalistic instincts of its performers. Israeli choreographer Hofesh Schechter, drawing influence from his experiences with the famed Batsheva Dance Company and its powerhouse director Ohad Naharin, found the disturbing core in his 40-minute buildup. As these men, in street garb – t-shirts and hoodies – walk ape-like, loose-armed and low to the ground, their athletic sparring, hand-to-hand combat, full-force runs and dives into the floor, ultimately coalesce in a menacing mélange. Is it protest or riot? Hard to tell, but the final king-of-the-hill image — one red-shirt-clad man reaching the apex of a clump of bodies his first raised — could be in solidarity or protest. And, in a season awash in domestic and international unrest, “Uprising,” with its massive large group movement, built into a cri de coeur akin to what happened on streets the world over in 2015.

The Washington Ballet Artistic Director Septime Webre has been delving into American literary classics and on the heels of his successes with both F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, in February his fearless chamber-sized troupe unveiled his latest: a full-length Sleepy Hollow, based, of course, on the ghostly literary legend by Washington Irving. But more than just a haunted night of ballet, Webre’s Sleepy Hollow delved into America’s early Puritan history, with a Reverend Cotton Mather character and a scene featuring witches drawn from elements of the Salem witch trials, expanding the historical and literary context of the work. This new dramatization in ballet, featuring a rich score by Matthew Pierce; well-used video projections by Clint Allen; and scenery by Hugh Landwehr; focuses on the tale of an outsider, Ichabod Crane – a common American literary trope. Choreographically Webre has smartly drawn not only on the expected classical ballet vocabulary, but he also tapped American folk dances and early and mid-20th century modern dance influences to expand the dancers’ roles for greater expressivity and storytelling. Guest principal Xiomara Reyes played the lovely love interest, Katrina Van Tassel, partnered by Jonathan Jordan. It’s hard to say whether this one will become a classic, but Webre’s smartly and carefully drawn characterizations and multi-generational arc in his approach to the Irving’s story expanded the options for contemporary story ballets.

Gallim Dance, a Brooklyn-based contemporary dance company founded by choreographer Andrea Miller, made its D.C. debut at the Lansburgh Theatre in April. Miller danced with Batsheva Ensemble, the junior company of Israel’s most significant dance troupe, and she brings those influences drawn from the unique methodology Naharin created. Called “gaga,” this dance language frees dancers and other movers to tap both their physical pleasure and their highest levels of experimentation. In “Blush,” this pleasure and experimentation played out with Miller’s three women and three men who dive head first into loosely constructed vignettes with elegant vengeance. With a primal sense of attack as they face off on the stage taped out like a boxing ring. Miller’s title “Blush” suggests the physiological change in a person’s body, their skin tone and during the course of “Blush,” transformations occur as the dancers, painted in Kabuki-like white rice powder, begin to reveal their actual skin tones – their blush. In so doing, they become metaphors for shedding a protective outer layer to reveal their inner selves.

The Washington Ballet continued its terrific season with the company’s much ballyhooed production of Swan Lake, at the smaller Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in April. It garnered international attention for Webre’s casting: ballet “It” girl Misty Copeland, partnered by steadfast senior company dancer Brooklyn Mack, became purportedly the first African American duo in a major American ballet company to dance the timeless roles of Odette/Odile and Siegfried, respectively. But that’s not what made this Swan Lake so memorable, and mostly satisfying. Instead, credit goes to former American Ballet Theatre principal Kirk Peterson, responsible for the indelible staging and choreography, following after, of course, Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. He drew exceptional performances from this typically less than classical chamber-sized troupe. The corps de ballet, supplemented by senior students and apprentices, really danced like a classical company. As well, Peterson, who has become an expert in resuscitating classics, returned little-seen mime passages to the stage, bringing back the inherent drama in this apex of story ballets. My favorite is the hardly seen (at least in the U.S.) passage when Odette, on meeting Siegfried in the forest in act II, tells him the story of her mother, evil Von Rothbart’s curse and the lake, filled with her mother’s tears, as she gestures in a horizontal sweep to the watery backdrop and brings her forefingers to her eyes indicating dropping tears. Live music was provided by the Evermay Chamber Orchestra and made all the difference for the dancers, even though the company’s small size meant the act III international character variations were cut. While the hype focused on the Copeland debut, she didn’t own or carry the ballet, and here Mack was a solid, but not entirely warm Siegfried. This Swan Lake truly soared truly through the corps, supporting roles and staging.

June brought the Polish National Ballet, directed by Krzysztof Pastor, to the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in lovely evening of contemporary European works. The small company – 11 women and a dozen men – are luscious and intelligent dancers who can captivate in works that push beyond staid classical technique. Pastor’s program opener, “Adagio & Scherzo,” featuring Schubert’s lyricism, twists, winds, and unfurls in pretty moments. There is darkness and light, both in the choreography and in designer Maciej Igielski’s illumination, which matches the shifting moodiness of the score. Pastor’s movement language is elegant, but not constrained, his dancers breathe and stretch, draw together and nuzzle in more ruminative moments, then split apart. In his closer “Moving Rooms” we first meet the dancers arranged in a checkerboard pattern on a black stage, each dancer contained in an single box of light. Using the sometimes nervously itchy score by Alfred Schnittke and Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki, the dancers, clad in flesh colored leotards, used their legs and arms in sharp-edged angles and geometries. But the centerpiece of the evening was a new “Rite of Spring” – yes, to that Mt. Everest of scores by Igor Stravinsky – this one is choreographed by French-Israeli Emanuel Gat. Danced on a red carpet, the five dancers ease into a counterintuitive tango of changing partners, always leaving one dancer as the odd one out. The smooth and slightly sensuous salsa is the basis for the work’s movement sinuous vocabulary, as it quietly builds like a slowly simmering pot put to boil.

Man and machine – or in this case – dancer and computerized robot – meet in Taiwanese-born choreographer and dancer Huang Yi’s 50-minute work. The evening presented in The Clarice’s Kogod Theater, its black box at the University of Maryland in September, provided a merging of art and technology. KUKA, the German-made robot, used in factories around the world to insert parts that build autos and iPads, has become a companion and artistic partner for Yi. Performing to a lushly classical score of selections from Bach and Mozart, Yi, clad in a dark suit, dances with, beside and around the singular movable robot arm sprouting from KUKA’s bright orange base. There are moments of serendipity, when the two seem to be communing in a duet of machine and motion, and others, in the dimly lit work, when each strays off on a tangent – robot and human, may move side by side, or even together, but only one inhabits a spiritual profound space of flesh, blood and breathe. That was my take away from this intriguing experiment in technology and dance. Yi is at the forefront of merging art with new technology and his experimentation – he programmed the robot – is on the cutting edge, but the work doesn’t cut to the quick. Still, orange steel and computer chips don’t trump muscle, bone, flesh and spirit. I would like to see more of Yi’s slippery, easy silken movement, in better light and with living breathing partners.

Man and machine – or in this case – dancer and computerized robot – meet in Taiwanese-born choreographer and dancer Huang Yi’s 50-minute work. The evening presented in The Clarice’s Kogod Theater, its black box at the University of Maryland in September, provided a merging of art and technology. KUKA, the German-made robot, used in factories around the world to insert parts that build autos and iPads, has become a companion and artistic partner for Yi. Performing to a lushly classical score of selections from Bach and Mozart, Yi, clad in a dark suit, dances with, beside and around the singular movable robot arm sprouting from KUKA’s bright orange base. There are moments of serendipity, when the two seem to be communing in a duet of machine and motion, and others, in the dimly lit work, when each strays off on a tangent – robot and human, may move side by side, or even together, but only one inhabits a spiritual profound space of flesh, blood and breathe. That was my take away from this intriguing experiment in technology and dance. Yi is at the forefront of merging art with new technology and his experimentation – he programmed the robot – is on the cutting edge, but the work doesn’t cut to the quick. Still, orange steel and computer chips don’t trump muscle, bone, flesh and spirit. I would like to see more of Yi’s slippery, easy silken movement, in better light and with living breathing partners.

Camille Brown went deep in mining her childhood experiences in Black Girl: Linguistic Play, presented by The Clarice in the Ina & Jack Kay Theatre in October. The evening-length work draws on Brown’s and her dancers’ playground experiences, first as young girls playing hopscotch, double dutch jump rope and sing-songy hand clapping games. On a set of platforms, chalk boards that the dancers color on and hanging angled mirrors designed by Elizabeth Nelson, Brown and her five women dancers inhabit their younger selves, in knee socks, overall shorts, and all the gum-chewing gumption and fearlessness that seven-, eight- and nine-year-olds own when they’re comfortable in their skin. As the piece, featuring a live score of original compositions and curated songs played by pianist Scott Patterson and bassist Tracy Wormworth hit all the right notes as the performers matured and grew before our eyes from nursery rhyming girls chanting “Miss Mary Mack” to hesitant pre-adolescents, fidgeting and fighting mean-girl battles, to teens on the cusp of womanhood – and uncertainty. The work is a vibrant and vivid rendering of the secret lives of the little seen and less heard experiences of black girls. The movement is pure play: physical, elemental, skips and hops, the stuff of recess and lazy summer days. But there are moments of deep recognition, particularly one where an older sister or mother figure gently, carefully, lovingly plaits the hair of one of the girls. Its quiet intimacy, too, speaks volumes.

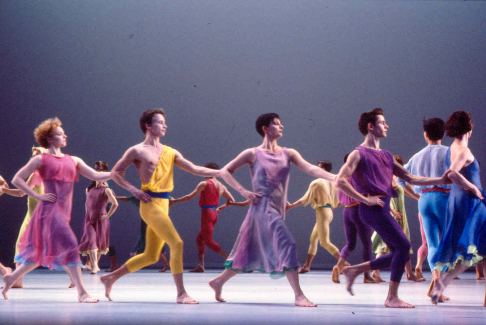

The dance event of the year was likely the much heralded 50th anniversary tour celebrating Twyla Tharp’s choreographic longevity and creativity. For the occasion at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater in November, she pulled together a 13-member ensemble of some of her long-time dancers and some younger favorites – multi-talented performers who can finesse a quick footed petit allegro or execute a jazzy kick-ball-change and slide sequence or bop and rock in bits of freestyle improvisation with equal skill. For the two Tharp did not revive earlier masterpieces, instead she paid a sort of homage to her elf with a pair of new works – “Preludes and Fugues” and “Yowzie.” Each had elements of hat smart synchronicity that Tharp favors, her beloved little balletic passages that she came to embrace after years of more severe post modernism, and her larky, goofy wiggles, scrunches, and witty physical jokes, like pairing the “tall” girl with the shortest guy in the company, or little games of tag or chase and odd-one-out that are interspersed in both works. “Preludes and Fugues” was preceded by “First Fanfare,” featuring a herald of trumpets composed by John Zorn (and performed by the Practical Trumpet society). The two works, one a bit of appetizer, the other the first course, bled into each other and recalled influences of Tharp’s earlier beloved choreography, especially the indelible ballroom sequences and catches of “Sinatra Suite.” “Preludes and Fugues” is as staunch piece set to Bach fugues that Tharp dissects choreographically with precise footwork, intermingling couples, groups and soloists and her eye for the “everything counts” ethos of post-modernism where ballet and jazz, loose-limbed modern and a circle of folk like chains all blend into a whole.

“Yowzie” is brighter, more carefree, recalling the unbridled energy of a New Orleans Second Line with its score of American jazz performed and arranged by Henry Butler, Steven Bernstein and The Hot 9. Dressed in mismatched psychedelia by designer Santo Loquasto the dancers grin and mug through this more lighthearted romp featuring lots of Twyla-esque loose limbs, shrugs, chugs and galumphs along with Tharpian incongruities: twos playing off of threes, boy-girl couplings that switch over to boy-boy pairs, and other hijinks of that sort. The dancers have fun with the work, its floppiness not belying the technical underpinnings that make the highly calibrated lifts, supports, pulls and such possible. The carnivalesque atmosphere feels partly like old-style vaudeville, partly like Mardi Gras. In the end though, both works are Twyla playing and paying homage to Twyla – they’re both solid, smart and well-crafted. They’re not keepers, though, in the way “In the Upper Room,” “Sinatra Suite,” or “Push Comes to Shove” were earlier in her career.

Samita Sinha’s bewilderment and other queer lions is not exactly dance or theater, but there’s plenty of movement and mystery and beauty in her hour-long work, which American Dance Institute in Rockville presented in early December. In a year of no Nutcrackers for this dance watcher, this was a terrific antidote to the crushing commercialization of all things seasonal during winter holidays. Sinha, a composer and vocal artist, draws on her roots in North Indian classical music as well as other folk, ritual and classical music traditions. Together with lighting, electronic scoring, a collection of props and objets (visual design is by Dani Leventhal), she has woven together a world inhabited by creative forces and energies from across genres and encompassing the four corners of the aural world. Ain Gordon directed the piece, which sometimes featured text, sometimes just vocalizing, sometimes movement as Sinha and her compatriots on stage Sunny Jain and Grey Mcmurray trade places, come together to play on or work with a prop, like a fake fur vest or scattered collected chairs and percussive instruments. There were eerie keenings, and deep rumbles, higher pitched vocalizations, cries, exhales, sighs, electric guitar and steel objects banged together, all in the purpose of building a world of pure and unclichéd vocal resonance. It would be too easy to compare her to Meredith Monk and Sinha is far less artistically self-conscious and precious. She is most definitely an artist to follow. Her vision and talent, keen eye and gracious presence speak – and sing – volumes.

© 2015 Lisa Traiger

Published December 31, 2015

Tantalize and Tease

“Stripe Tease”

Choreography by Chris Schlichting, in collaboration with performers Dolo McComb, Dustin Maxwell, Laura Selle Virtucio, Max Wirsing, Pareena Lim and Tristan Koepke

Music by Jeremy Yivisaker and Alpha Consumer, featuring JT Bates and Jim Anton

Design and Installation by Jennifer Davis

Lighting by Joe Levasseur

Costumes by Chris Schlichting

American Dance Institute, Rockville, Md.

October 2, 2015

By Lisa Traiger

Minneapolis-based choreographer Chris Schlichting’s “Stripe Tease” feels both intimate and expansive, drawing on his knack for specificity in inventive movement phrasing and his love of interior design and costuming, the piece evolves in organic and intriguing ways. As his layers build to full-blown climatic kineticism, the finely crafted hour-long work teases out lovely passages crisply performed accompanied live by the fabulous three-piece ensemble Alpha Consumer. Schlichting and “Stripe Tease” made a metropolitan Washington, D.C. area premiere October 2 and 3 at American Dance Institute, one of three commissioning partners through the National Performance Network.

Minneapolis-based choreographer Chris Schlichting’s “Stripe Tease” feels both intimate and expansive, drawing on his knack for specificity in inventive movement phrasing and his love of interior design and costuming, the piece evolves in organic and intriguing ways. As his layers build to full-blown climatic kineticism, the finely crafted hour-long work teases out lovely passages crisply performed accompanied live by the fabulous three-piece ensemble Alpha Consumer. Schlichting and “Stripe Tease” made a metropolitan Washington, D.C. area premiere October 2 and 3 at American Dance Institute, one of three commissioning partners through the National Performance Network.

Beginning in silence, two men draw a line in the air, then in tight unison relish a series of complex gestural phrases they deliver with uncommon grace and femininity – wilting hands, melting elbows, sloped, rolling shoulders. There’s an unspoken subversion of masculinity – or is it usurping of femininity – in these men languishing in seemingly womanly motifs, which remains a subtle theme throughout the piece. With a softness and uncommon delicacy, this indulgent beauty and oozing liquid grace multiplies as additional dancers enter, singly and then in pairs, a structure that becomes a motif throughout the evening. The six performers, clad in couture-level black shorts or slacks, tops with slashes, visible zippers, fine pleats and high necks (all designed by Schlichting), relish the opulent, choreographic phrasing that allows for undulations contrasting with saber-like slashes or occasional audible stomps.

Guitarist Jeremy Ylvisaker’s accompanying music, played live with drummer JT Bates and bassist Jim Anton, provides a rock-inspired and yet easygoing pop inflected foreground on which the dancers parse out their exquisitely evolved phrases. What sings in the piece as it develops are the juxtapositions among the choreographed sections – swift, semaphoric gestures that look like a protolanguage not yet translated – and the building drama unveiled from visual designer Jennifer Davis with an assist from lighting designer Joe Levasseur. At first a study in black, soon that backdrop rises to reveal a sea of color-school stripes in multihued fluorescents and foils. Think late 1960s, early 1970s, bathroom wallpaper and you’ll get the idea. Levasseur’s lighting, too, has a throwback feel, with his sometimes moody, sometimes hot fluorescent choices that open up the performers’ space into the audience.

Playing with duets, danced in close unison side by side, but never truly partnering – there are no lifts, holds or supports in the piece – Schlichting relishes his own expressions of formalism, unleashing his dancers like indie fashion models for a take-no-prisoners fashion house like Rick Owens’ – their tough, hard stares intimidating one moment, then their eye scans an invitation the next. At one point the dancers become bored cat-walking models, pacing the stage in a broad loping gait, then mounting the steps into the audience, to pause and pose. Off to the side in an exit alley, a duo performs small sidebar movements, hands and forearms swiveling and waving like little handkerchiefs whipping in the wind. As the Schlichting with Ylvisaker’s musical support builds a crescendo into the work, the stage design elements have their own fashionable reveal. Stage hands, smartly dressed in black with vivid belts, draw back curtains and later side panels in each wing to reveal two tigers painted in fluorescent stripes of neon tape glowing orange, green and pink. Have all the choreographic movement markings been a tease for the stripes – or vice versa?

No matter. How easy it is to get drawn into Schlichting’s world, where a dancer finger tracking a line in space early on then eggs forward into a rich collection of intricate and ever-evolving hands, arms shoulders looping in circles, cupping hands, full-blown and half-way there. Meaning and story here are, of course, subverted for the pure beauty and delicacy captured by the six fine performers: Dolo McComb Dustin Maxwell, Laura Selle Virtucio, Max Wirsing, Pareena Lim and Tristan Koepke. The work is far more than a tease, it’s a tantalizing collection of treasures with rewards for the patient and caring viewer.

Photos: top, Bill Cameron; bottom, Gene Pittman, Walker Art Center

Published October 3, 2015

© 2015 Lisa Traiger

Found Among Chaos

“Find Yourself Here”

Joanna Kotze, with Jonathan Allen, Zachary Fabri, Asuka Goto, Stuart Singer and Netta Yershalmy

American Dance Institute

Rockville, Md., April 24, 2015

World premiere

By Lisa Traiger

Structure amid chaos and chaos amid structure — these two precepts underlie South African-born, New York-based choreographer and dancer Joanna Kotze’s latest, “Find Yourself Here.” The world premiere, presented by American Dance Institute April 24-25, 2015, in Rockville, Md., tucked deep in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., examines space as both a performative and a static environment while drawing the audience to come to its own conclusions about the work that rattles expectations about dance and art, collaboration and individuality, harmony and tension. The project, which draws together three dancers and three visual artists, along with a composer/sound designer, is imbued with smart, philosophical underpinnings articulated with attractively designed and executed movement sequences and art-making processes.

Structure amid chaos and chaos amid structure — these two precepts underlie South African-born, New York-based choreographer and dancer Joanna Kotze’s latest, “Find Yourself Here.” The world premiere, presented by American Dance Institute April 24-25, 2015, in Rockville, Md., tucked deep in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., examines space as both a performative and a static environment while drawing the audience to come to its own conclusions about the work that rattles expectations about dance and art, collaboration and individuality, harmony and tension. The project, which draws together three dancers and three visual artists, along with a composer/sound designer, is imbued with smart, philosophical underpinnings articulated with attractively designed and executed movement sequences and art-making processes.

Upon entering ADI’s black box, the dancers and artists — who during the performance are interchangeable and, only after a second look at the program did I realize the distinction between “dancer” and “visual artist” was supposed to carry some importance, for it certainly wasn’t recognizable — are on task, laying down brightly colored linoleum tiles in right angular patterns and sequences. On the black floor the result was a pixilated riot of blues, yellows, tangerines and fuschias placed with care but at seemingly random order. As the performers gather and stack the tiles up at the back of the stage, a meditative process settles in. Into this rush of color, the performers, wearing Mary Jo Mecca’s color-drained white and gray athletic wear — a pop of hue visible only in the colorful selection of Keds — mostly blend in, save for Zachary Fabri, who clownishly skips and tiptoes through the space, breaking down that invisible wall between performer and watcher to make direct eye contact — ultimately to the delight of audience members in the first two rows.

A jogging sequence for all six their hands held paw-like in front of their chests — or perhaps it’s a post-modern parade — leads the column of dancers around in expansive patterns, their pattering feet and breath providing a living sound score, joined by the subtle and spare mixed-in sounds by Ryan Seaton. Later a duet for paper-doll-thin Kotze and fellow dancer Netta Yerushalmy has them lunging, diving, skipping and braiding through each other’s movement sequences.

What’s most intriguing in the piece, though, is the building and taking apart, the creation and destruction, of the carefully planned structures in the stage environment, which itself becomes a canvas on which the work unfurls. Smaller squares of wood and Styrofoam stand stacked in one back corner, poles covered in fluorescent glow tape rise like stripped trees along one side of the stage, and small, hand-sized colored plastic squares are lined up on the opposite side like a child’s Colorforms project. Asuka Goto wields a roll of white tape that she uses to splice the horizontality of the stage, laying it down then simply pulling it up and crumpling it in a ball. Soon all this organization, those carefully placed tiles and lines, squares and angles, colors and patterns, degrades into chaos as dancers and artists mingle and whip everything up like a cake batter gone awry in a Mixmaster.

By “Find Yourself Here’s” ending moments, the stage has gained a mass of items and objects, dancers and artists, they’re all one and the same, the neatness and the care of the early moments lost in the muddy convulsion as it all gets thrown together. And it’s a glorious mess as dancers and artists — performers, all — intermingle and stack and toss, regroup and remix the various tiles and squares, tape and sundries. Care has become chaos, and at the root of it all is the realization that we — the audience in that broken gaze across that invisible dramatic line — are them — or at least we could, in a dream sequence, be them. The metaphor becomes clear in the crazy discombobulation of it all: life is a Sisyphusian task, we spend our days pushing that bolder up the hill again and again, only for it to roll down. Then we start over. Kotze’s dance is a dance of life, vivid, chaotic, unexpected, moments of subtly and unbridled hamminess, joyful and reserved.

A 2014 Bessie winner for new choreography, Kotze, like many of the current crop of artists ADI is bringing to its Incubator Program, has borrowed inspiration from 1960s Judsonian ideas — ordinary movement as performance, task-oriented movement, game-like structures, an intermingling of multiple disciplines, a breakdown of the artist/audience relationship, and, of course, abstraction as metaphor, or not. But for Kotze, with her background and training in architecture, “Find Yourself Here” is no re-tread of 1960s ideals. The work lives in real time — and speaks to audiences today who find the charm, lively brightness and vivid beauty, and the unholy mess of their own lives in Kotze’s poetic piece.

Photo courtesy American Dance Institute

Published April 25, 2015

© 2015 Lisa Traiger

A Year in Dance: 2014

By Lisa Traiger

My year 2014 in dance opened in January with the return of the now annually visiting Mariinsky Ballet to the Kennedy Center Opera House. Though the company brought Swan Lake, the company’s signature work – created on this most famous classical troupe by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov in 1895 – was not what we saw. Instead the “Sovietized” Konstantin Sergeyev 1950 version, filled with pomp and additions startling for Western audiences (a second corps of black swans, for example, in the “white” act), was on offer. Ultimately, the true star was the singular corps de ballet. Who can resist the Mariinsky’s 32 perfectly synchronized white swans in act two? The impeccable Vaganova training remains one of the Mariinsky’s most essential hallmarks. Even standing still, the corps breathes together as one body; in stillness they’re dancing. The result is simply stunning and awe-inspiring, ballet at its best.

My year 2014 in dance opened in January with the return of the now annually visiting Mariinsky Ballet to the Kennedy Center Opera House. Though the company brought Swan Lake, the company’s signature work – created on this most famous classical troupe by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov in 1895 – was not what we saw. Instead the “Sovietized” Konstantin Sergeyev 1950 version, filled with pomp and additions startling for Western audiences (a second corps of black swans, for example, in the “white” act), was on offer. Ultimately, the true star was the singular corps de ballet. Who can resist the Mariinsky’s 32 perfectly synchronized white swans in act two? The impeccable Vaganova training remains one of the Mariinsky’s most essential hallmarks. Even standing still, the corps breathes together as one body; in stillness they’re dancing. The result is simply stunning and awe-inspiring, ballet at its best.

Compagnie Kafig’s hip hop with a French accent and a circus flair rocked the Kennedy Center in February. Founded in 1996 by Mourad Merzouki in a suburb of Lyon, Kafig’s all-male troupe of athletic dancers flip and tumble, punching out percussive beats and floor work that toggle between their North African roots and b-boy street moves. Merzouki’s latest interest is capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian dance-cum-martial-art. His “Agwa” featured about 100 cups of water, arrayed in grids, poured and re-poured, along with plenty of circusy tricks and surprises. Hip hop dance has for a generation-plus moved beyond its inner-city, thug-life street demeanor; we see the results daily in popular culture, on television and in suburban dance studios. Kafig’s creative and expansive approach drawing from North African and Afro Brazilian rhythms and French circus opens up a whole new world for this home-grown vernacular form.

Compagnie Kafig’s hip hop with a French accent and a circus flair rocked the Kennedy Center in February. Founded in 1996 by Mourad Merzouki in a suburb of Lyon, Kafig’s all-male troupe of athletic dancers flip and tumble, punching out percussive beats and floor work that toggle between their North African roots and b-boy street moves. Merzouki’s latest interest is capoeira, the Afro-Brazilian dance-cum-martial-art. His “Agwa” featured about 100 cups of water, arrayed in grids, poured and re-poured, along with plenty of circusy tricks and surprises. Hip hop dance has for a generation-plus moved beyond its inner-city, thug-life street demeanor; we see the results daily in popular culture, on television and in suburban dance studios. Kafig’s creative and expansive approach drawing from North African and Afro Brazilian rhythms and French circus opens up a whole new world for this home-grown vernacular form.

In April, Rockville’s forward-thinking American Dance Institute presented the legendary post modernist Yvonne Rainer. Now 79 and still making new work, Rainer is credited in the 1960s with coining the term post-modern for dance and as part of the experimental Judson Church movement taking dance into new, uncharted realms. She famously penned her “No” manifesto – “No to spectacle. No to virtuosity. No to transformations and magic and make-believe. No to the glamour and transcendency of the star image” – which has become a de rigueur short reading for any young modern dancer looking to develop a choreographic voice. In it Rainer encouraged a re-thinking of dance without virtuosity, technique, story and beauty. Dance could be the “found movement” we see on the streets every day. For her evening at ADI’s blackbox theater, Rainer didn’t dance, but her five dancers, whom she lovingly dubbed her Raindears, did. “Assisted Living: Good Sports 2” and “Assisted Living: Do You Have Any Money?” were recent, from 2011 and 2013 respectively. They were still steeped in Judsonian traits – lots of game-like patterns and structures as the Raindears jogged the stage like a ragged army of enlisted 5th graders on recess; a montage of unusual music and spoken sections, drawing from classics, opera, popular mid-20th century songs, readings and quotes on economics and more. A dancer drags a mattress, dancers hoist and carry other dancers like movers, Rainer reads and observes from a comfortable perch on an easy chair. First timers to this type of highly conceptual work might leave scratching their heads. But there’s a method to the madness and the accumulation of moments and movement quotes from ballet, tap and vaudeville at various points. Here we have the post-modern notion where everything counts: everything and the kitchen sink get thrown together to make a work. But there’s craft and method behind this madness, this everyone-in approach. Rainer, for me, built a structure that resonated deeply on an emotional level. This pair of works made me think of wrapping up a lifetime, and, more personally, of easing my own parents into their final years: packing up, putting away, remembering and forgetting, burying. This was post-modernism with a new level of poignancy. Though not narrative, it spoke to me in far-reaching ways. When I chatted with Rainer after, I told her how moved I was and how it made me think of my parents in their final years. She acknowledged that while in the studio creating, she was dealing with similar end-of-life issues with a dying brother. Even Rainer, the purest of post-modernists, has come to a place of remembrance and meaning in ways that were unforgettable.

One of the year’s most anticipated events was the re-opening of the region’s most prolific dance presenter, Dance Place, which has long been a mainstay of the now revitalizing Brookland neighborhood of northeast Washington. In June the site specific piece “INSERT [ ] HERE” inaugurated the newly renovated studio/theater. Sharon Mansur, a University of Maryland College Park dance professor, and collaborator Nick Bryson, an Ireland-based independent artist and improviser, fashioned a site-specific piece that took small groups through the space – introducing both the public areas like the studio/theater and spacious new lobby to never seen recesses like the dank underground basement, the artists’ new dressing rooms, rehearsal rooms and a long narrow corridor of open desks where most of the staff put in their hours. Audience members were allowed to meander and pause, take note of a moment beneath the bleachers where Baltimore choreographer Naoko Maeshiba was part girl-child zombie, part Japanese butoh post-apocalyptic figure. Upstairs in a rehearsal room, Mansur and Bryson parsed out parallel neatly improvised solos that reflected and spoke through movement to each other. In a dressing area former D.C. improviser/choreographer Dan Burkholder fashioned his movement phrases with silky directness amid a room of candles and found natural objects. The main stage filled with a wash of dancers sweeping in with celebratory bravado: An auspicious, memorable, and entirely perfect way to christen the space.

One of the year’s most anticipated events was the re-opening of the region’s most prolific dance presenter, Dance Place, which has long been a mainstay of the now revitalizing Brookland neighborhood of northeast Washington. In June the site specific piece “INSERT [ ] HERE” inaugurated the newly renovated studio/theater. Sharon Mansur, a University of Maryland College Park dance professor, and collaborator Nick Bryson, an Ireland-based independent artist and improviser, fashioned a site-specific piece that took small groups through the space – introducing both the public areas like the studio/theater and spacious new lobby to never seen recesses like the dank underground basement, the artists’ new dressing rooms, rehearsal rooms and a long narrow corridor of open desks where most of the staff put in their hours. Audience members were allowed to meander and pause, take note of a moment beneath the bleachers where Baltimore choreographer Naoko Maeshiba was part girl-child zombie, part Japanese butoh post-apocalyptic figure. Upstairs in a rehearsal room, Mansur and Bryson parsed out parallel neatly improvised solos that reflected and spoke through movement to each other. In a dressing area former D.C. improviser/choreographer Dan Burkholder fashioned his movement phrases with silky directness amid a room of candles and found natural objects. The main stage filled with a wash of dancers sweeping in with celebratory bravado: An auspicious, memorable, and entirely perfect way to christen the space.

Long-time D.C. stalwart Liz Lerman, who decamped from her own Takoma Park-based company the Dance Exchange in 2011, returned to the area with another broadly encompassing work, Healing Wars, which had its world premiere at Arena Stage’s intimate Cradle in May. The audience was welcomed in through the stage door, where a “living museum” of characters – Clara Barton penning letters, a Civil War soldier splayed on a kitty corner hospital cot, a woman pouring water libation as a spirit of a runaway slave, and the very real veteran of the recent war in Afghanistan, Paul Hurley, a former U.S. Navy gunner’s mate and graduate of Duke Ellington School for the Arts in Washington, D.C., conversing with Hollywood actor Bill Pullman. Healing Wars examines war, injury, death, and recovery from multiple perspective spanning two centuries: the Civil War era and the 21st century. This was entirely and exactly Lerman’s wheelhouse. The piece was didactic, thought provoking, head scratching all at once. And it does what movement theater should: inspire and challenge. Lerman was determined with this project to bring the present day wars and their aftermaths home for America’s largest and most divisive war, the Civil War, touched nearly every household. By drawing together these disparate but not dissimilar historical moments, along with the science, medical advances, politics and, of course, personal experiences, Lerman has contemporary audiences reflect that as individually painful as war traumas are, the suffering that results is our nation’s burden to bear. Lerman, here, through her compelling dance theater underscored the gravity of that burden.

In September, Deviated Theatre returned to Dance Place with a steampunk quest story envisioned by choreographer Kimmie Dobbs Chan and director Enoch Chan. For the evening-length Creature, the costumes — wings, netting and accoutrements draped and shaped by Andy Christ with second act headpieces full of wire-y netting and fanciful shapes by Dobbs Chan — are astonishing. The dancing here was among the best technically of the locally based dance troupes this year. The primarily female cast stretches like Gumbies, soars from an aerial hoop, maneuvers on two legs or four limbs, crab walking, crawling, scooting, loping in bug-like, inhuman ways. Though the apocalyptic fairy tale meanders, the oddball weirdness – eerie, esoteric, eclectic – that Chan and Chan invent continues to endear.

October brought a troupe from Israel, where contemporary dance continues to be a hotbed of creativity. Vertigo Dance from Jerusalem brought choreographer Noa Wertheim’s Reshimo, with its company of nine unfettered dancers who take viewers on an emotional journey. “Reshimo,” a term from Kabbalah – Jewish mysticism – suggests the impression light makes, the afterimage. The 55-minute work presented an ever-evolving landscape of singular movement statements, accompanied by Ran Bagno’s rich and varied musical score, which modulates between violin, cello, synthesizers and kitschy retro-pop selections. Sexy trysts, playful romps, casual walks and a moment of frisson, explosive and shattering, fully animate the choreographic voice filling the work with resonant ideas.

October brought a troupe from Israel, where contemporary dance continues to be a hotbed of creativity. Vertigo Dance from Jerusalem brought choreographer Noa Wertheim’s Reshimo, with its company of nine unfettered dancers who take viewers on an emotional journey. “Reshimo,” a term from Kabbalah – Jewish mysticism – suggests the impression light makes, the afterimage. The 55-minute work presented an ever-evolving landscape of singular movement statements, accompanied by Ran Bagno’s rich and varied musical score, which modulates between violin, cello, synthesizers and kitschy retro-pop selections. Sexy trysts, playful romps, casual walks and a moment of frisson, explosive and shattering, fully animate the choreographic voice filling the work with resonant ideas.

My year in dance ended on a high note, another company from Israel: the country’s most intriguing, Batsheva Dance Company based in Tel Aviv, returned to the Kennedy Center’s Opera House in November with the area premiere of Sadeh21. The work, by the company’s prolific and long-time choreographic master Ohad Naharin, shows off the dancers’ distinctive abilities to inhabit and embody movement in all its capacities. “Sadeh,” Naharin told me, means field, as in field of study, and the work unspools in vignettes or scenes – some solos, some duets or small groups, some full the company – which are labeled by number on the half-high back wall, the set designed by Avi Yona Bueno. Moments funny and disturbing, sexy and silly include movement riffs that combine the refined and the repulsive, an extended sequence of screaming, another where the men in unison ape and stomp like fools in flouncy skirts. Naharin’s music, like his rangy movement, is erratic, shifting from classical to pop, severe to silly to sweet in game-like fashion. The set design, that imposing back wall, is freighted with multiple meanings. A wall in Israeli context recalls both the ancient Western Wall — the supporting wall of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. But in contemporary terms the wall suggests the one built by the Israeli government to separate Israel proper from the West Bank. Both a protection and a burden, it’s a constant reminder that peace remains an achingly elusive ideal. For Naharin, the on-stage wall literally became a jumping off point. Dancers scrambled up, stood atop the ledge and dove into the inky blackness. That ending is simply gorgeous. Again and again, dive after dive, were they leaping to their freedom, to their deaths, or were they doves, soaring skyward? Continuously, as the music faded and the lights rose, credits rolled like a movie on the wall, as dancers climbed and dove. A taste of infinity. From earth to heaven and back again. I could have watched those final moments forever, they felt so raw, yet whole, risky but real. Final but indefinite. Life as art. Art as life. Batsheva ended my year in dance on a soar.

My year in dance ended on a high note, another company from Israel: the country’s most intriguing, Batsheva Dance Company based in Tel Aviv, returned to the Kennedy Center’s Opera House in November with the area premiere of Sadeh21. The work, by the company’s prolific and long-time choreographic master Ohad Naharin, shows off the dancers’ distinctive abilities to inhabit and embody movement in all its capacities. “Sadeh,” Naharin told me, means field, as in field of study, and the work unspools in vignettes or scenes – some solos, some duets or small groups, some full the company – which are labeled by number on the half-high back wall, the set designed by Avi Yona Bueno. Moments funny and disturbing, sexy and silly include movement riffs that combine the refined and the repulsive, an extended sequence of screaming, another where the men in unison ape and stomp like fools in flouncy skirts. Naharin’s music, like his rangy movement, is erratic, shifting from classical to pop, severe to silly to sweet in game-like fashion. The set design, that imposing back wall, is freighted with multiple meanings. A wall in Israeli context recalls both the ancient Western Wall — the supporting wall of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. But in contemporary terms the wall suggests the one built by the Israeli government to separate Israel proper from the West Bank. Both a protection and a burden, it’s a constant reminder that peace remains an achingly elusive ideal. For Naharin, the on-stage wall literally became a jumping off point. Dancers scrambled up, stood atop the ledge and dove into the inky blackness. That ending is simply gorgeous. Again and again, dive after dive, were they leaping to their freedom, to their deaths, or were they doves, soaring skyward? Continuously, as the music faded and the lights rose, credits rolled like a movie on the wall, as dancers climbed and dove. A taste of infinity. From earth to heaven and back again. I could have watched those final moments forever, they felt so raw, yet whole, risky but real. Final but indefinite. Life as art. Art as life. Batsheva ended my year in dance on a soar.

Lisa Traiger writes frequently on dance, theater and the arts. You may read her work in the Washington Jewish Week, Dance magazine and other publications.

(c) 2015 Lisa Traiger

A Personal Best: Dance Watching in 2012

Like many, my 2012 dance year began with an ending: Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Much was written on the closure of this 20th-century American treasure after more than 50 years, especially its final performance events on the days leading up to New Year’s Eve 2012. At the penultimate performance on December 30, the dancers shone, carving swaths of movement from thin air in the hazy pools of light spilling onto raised platform stages in the cavernous Park Avenue Armory space. A piercing trumpet call emanated from the rafters heralding the start of this one-of-a-kind evening. Pillowy, cloud-like installations floated above in near darkness. Throughout, snippets of Cunningham choreography – I saw “Crises,” “Doubles” and maybe “Points in Space” – came and went, moving images played for the last time, while audience members sat on folding chairs, observed from risers or meandered through the space, taking care not to step on the carpeted runways that the dancers used to travel from stage to stage.

I found it refreshing to get so close to the dancers after years of partaking of the Cunningham company in theatrical spaces, for me most commonly the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. Here the dancers became human, sweat beads forming on their backs, breathe elevated, hair matting down toward the end of the evening. Duets, trios, groups formed and dissolved in that coolly unemotive Cunningham fashion, with alacrity they would step off the stage and rest and reset themselves before coming back on again for another round of the complex alphabet of Cunningham bends, pelvic tilts, lunges, passes, springs, jumps and playful leaps. While the dancers energy surged, I felt time was growing short. The end near. I soon found myself on a riser standing directly above and behind music director Takehisa Kosugi who at the keyboard conducted the ensemble and held an digital stop watch. Journalists traditionally end their articles with – 30 –. Here, momentarily I got distracted with the numbers: 41’38”, 41’39”, 41’40”, 41’41” … And then within a minute Kosugi nodded and squeezed his thumb: at 42’40”. An ending stark, poignant, and by the book.

In January, the Mariinsky Ballet’s “Les Saisons Russes” program was an eye opener on many levels. The work of Ballets Russes that stunned Paris then the world from 1909 through 1914 under the astute and market-savvy vision of Serge Diaghilev, remains incomparable for audiences today. The triple bill of Mikel Fokine works wows with its saturated colors and vividly wrought choreographic statements, impeccably executed by Mariinsky’s stable of well-trained dancers. These three ballets – “Chopiniana” from 1908, and “The Firebird” and “Scheherazade” from 1910 – continue to pack a powerful punch, a century after their creation. The subtle Romanticism distilled with elan by the Mariinsky corps de ballet — from the perfection etched into their curved arms and slightly tilted heads, their epaulment unparalleled — makes one pine for a bygone Romantic era that likely never actually attained this level of technical grace and precision. With “Firebird,” the Russian folktale elaborately retold in dance, drama and vibrantly outlandish costumes, the flamboyant folk characters were part ‘80s rock stars, part science fiction film creatures. Finally, the bombast and melodrama of the Arabian Nights rendered through Fokine’s version of “Schererazade” danced as if on steroids provided outsized exoticism, with more sequined costumes, scimtars and false facial hair and the soap operatic performances to suit the pompous grandeur of the Rimsky-Korsakov score. Surely Diaghilev would have approved.

Also in January, Mark Morris Dance Group returned to the Kennedy Center Opera House with its brilliant L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, danced with humanity and glee to Handel’s oratorio, itself based on 17th-century pastoral poem by John Milton and the watercolor illustrations of William Blake. Morris – and Milton, Blake and Handel – each strove for a utopian ideal. This work draws together its disparate parts into one of the great dance works of the 20th century. Enough has been spoken and written about this glorious rendering in music, with the full-voiced Washington Bach Consort Chorus, wildly overblown and softly understated dancing from an expanded company of 24 elegant and spirited movers, and set design – vivid washes of color and light in ranging from flourish of springtime hues to fading fall colors — by Adrianne Lobel. L’Allegro was produced abroad, in 1988 when Morris and his company were in residence at the Theatre Royale de la Monnaie in Belgium, at a time and a place when dance received unprecedented financial and artistic support. I was struck by the open democratic feeling of the dancers, each on equal footing, soloists melding into groups, humorous bits shifting to serious interludes, no dancer stands out individually. For Morris, whose roots date back to folk dance, the community, the group, the natural feeling of people dancing together is valued above the singularity of solo dancing. It’s democracy – small d – at its best. Watching the work again this year, as dance companies large and small balance at the edge of a seemingly perpetual fiscal cliff, was a reminder of how small and cloistered American modern dance has become. We have few choreographers with the resources and the daring to attempt the bold and brash statements that Morris harnessed in L’Allegro.

Another company that leaves everything on stage but in an entirely different vein is Tel Aviv’s Batsheva Dance Company, which I caught at Brooklyn Academy of Music in March. Hora, an evening-length study in gamesmanship and internalized worlds made visible was created by company artistic director (and current world-renowned dance icon) Ohad Naharin. With his facetiously named Gaga movement language, dancers attained heightened sensitivity, not dissimilar to the work butoh masters and post-modernist strove for in earlier decades. And yet the steely technical accomplishment and steadfast allegiances to dancing in the moment that Gaga pulls from its best proponents makes Batsheva among the world’s most prized and praised contemporary dance companies. At BAM, the 60 minute work with its saturated colors and pools of shifting lighting by Avi Yona Bueno and music arranged by Isao Tomita featuring snippets from Wagner, Strauss, Debussy and Mussorgsky offers a smorgasbord of familiarity as the dancers parse oddly shaped lunges with hips askew, pelvises tucked under, ribs thrust forward and heads cocked just so. Odd and awkward, yet athletic and graceful, and undeniably daring Naharin mines his Batsheva dancers for quirks that become accepted as fresh 21st century bodily configurations. Though named Hora, the work has nothing whatsoever to do with the ubiquitous Jewish circle dance, yet after an evening with Batsheva, it’s hard not to feel like celebrating.

Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz in “Necessary Weather,” with lighting by Jennifer Tipton, photo: Stephanie Berger

In April, Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz glimmered in “Necessary Weather,” a subtle tour de force filled with small moments of great and profound drama and even, unexpectedly, a smile or two. The glide of a foot, cock of a head, even a raised eyebrow or tip of a hat from Rudner and Reitz resonated beneath the glow of Jennifer Tipton’s lighting, which in American Dance Institute’s Rockville studio theater, performed a choreography of its own glowing, fading, saturating and shimmering.

Also at ADI in May, Tzveta Kassabova created a rarified world – of the daily-ness of life and the outdoors. By bringing nature inside and onto the stage, which was strewn with leaves, decorated with lawn furniture, and, in a coup de theatre, a mud puddle and a rain storm. Her evening-length and richly rendered Left of Green, Fall, choreographed on a wide-ranging cast of 16 child and adult dancers and movers, featured sound design and original music with a folk-ish tinge by Steve Wanna. The work tugs at the outer corners of thought with its intermingling of hyper-real and imagined worlds. The senses also come into play: the smell of drying leaves, the crackly crunch they make beneath one’s feet and the moist-wet smell of fall is startling, particularly occurring indoors on a sunny May afternoon. Kassabova, with her flounce of bouncy curls and angular, sharp-cornered body, dances with a laser-like intensity. She’s ready to play, allowing the sounds and sights of children in a park, sometimes among themselves, other times with adults. She’s also game to show off awkwardness: turned in feet, sharp corners of elbows, hunched shoulders and flat-footed balances – providing refreshing lessons that beauty is indeed present in the most ordinary and the most natural ways the body moves.

The Paris Opera Ballet’s July stop at the Kennedy Center Opera House brought an impeccable rendering of one of the pinnacles of Romantic ballet: Giselle. And should one expect anything less than perfection when the program credits list the number of performances of this ballet by the company? On July 5, 2012, I saw the “760th performance by the Paris Opera Ballet and the 206th performance of this production,” one with choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot dating from 1841, transmitted by Marius Petipa in 1887 and adapted by Patrice Bart and Eugene Polyakov in 1991. Two days later it was 763. The POB still uses the 1924 set and costume designs of the great Alexandre Benois, adding further authenticity to the work. But nothing about this production is museum material. POB continues to breathe life into its Giselle.

Aside from making a pilgrimage to the imaginary graveside of the tragic maiden dancer two-timed by her admirer, it’s hard to find a more accurate and handsome production of this ballet masterpiece. Aurelie Dupont was a thoughtful and sophisticated Giselle, care and technical virtuosity evident in her performance, while her Albrecht, Mathieu Ganio, played his Romantic hero for grandeur. While the 40-something husband and wife duo of Nicholas Le Riche and Clairemarie Osta on paper make an unlikely Albrecht and Giselle, in reality their heartfelt performances were so intensely and genuinely realized at the Saturday matinee that they felt as youthful as Giselles and Albrechts a generation younger.

The production is as close to perfection on so many levels that one might ever find in a ballet, starting with a corps de ballet that danced singularly, breathing as one unit, most particularly in the act II graveside scene. The mime passages, too, were truly beautiful, works of expressive artistry many that in most companies, particularly the American ones, are dropped or given short shrift. Here the tradition remains that mime is integral to the choreography, not an afterthought but a moment of import. Most interesting was a (new to me) mime sequence by Giselle’s mother about the origins of her daughter’s affliction and how she will most definitely die (hands in fists, crossed at the wrists, held low at the chest). Later when the Wilis dance in act II, it becomes abundantly clear why their arms are crossed, though delicately, their hands relaxed: they’re the walking dead, zombies, if you will, of another era. Another unforgettable moment in POBs Giselle, is its use of tableaux at then ending moment of each act. Each act ends in a moment of frozen stillness – act one of course with Giselle’s death, act two with the resurrection of Albrecht. Each of these is captured in a stage picture, then the curtain dropped and rose again – and there the dancers stood, still posed in character. Stunning and memorable.

Each year in August the Karmiel Dance Festival swallows up the small northern Israeli city of Karmiel as upwards of reportedly 250,000 folk and professional dancers swarm the city for three days and nights of dance. From large-scale performances in an outdoor amphitheater to professional and semi-professional and student companies performing in the municipal auditorium and in local gymnasiums and schools to folk dance sessions on the city’s six tennis courts, Karmiel is awash in dance. I caught companies ranging from the silky beauty of Guangdong Modern Dance Company from China’s Guangzhou province, France’s Ballet de Opera Metz under the direction of Patrick Salliot, the youthful and vivacious CIA Brasileira De Ballet, where artistic director Jorge Texeira seeks out his youthful dance protégés from the streets and barrios of some of the poorest neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, Terrence Orr’s Pittsburgh Ballet Theater, and Israel’s Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, directed by Rami Be’er in a program of new works by young dancemakers. Maybe not the best that I saw, but the unforgettable oddity of the three-day festival was the headlining company, billed as the Cossack National Dance Troupe from Russia. In the grand folk dance tradition of the great Moiseyev company of Russia, these dancers, musicians and singers – numbering 60 strong – let the sparks fly, literally. With breathtaking sword play where white hot sparks truly did fly from the swords, to astounding acrobatic feats and graceful, feminine dances featuring smoothness, precision and delicate footwork parsed out in heeled character boots, the troupe was a hit. Few in the appreciative Israeli crowd – many of whom sang along to the old Russian folk songs buying into a mythic pastoral vision of the Cossack warriors – seemed aware of the irony of an audience of predominantly Israeli Jews heartily applauding a show titled “The Cossacks Are Coming!” The last time Jews were heard to say “The Cossacks are coming,” things didn’t turn out so well.

In September, Dance Place was fortunate to book one of the State Department’s CenterStage touring troupes at the top of its season. Nan Jombang, a one-of-a-kind family of dancers from the Indonesian island of Sumatra, provided a remarkable and moving evening in its North American premiere. Rantau Berbisik or “Whisperings of Exile” begins with a siren call, a female shriek that’s an alarm and cry of pain, that begins a journey of unexpected images. Ery Mefri, a dancer from Padang, on the western coast of Sumatra, has created a surprisingly original dance culture drawing from traditional tribal rituals, martial arts – randai and pencak silak – captivating chants and unusual body percussion techniques. But most unique about Mefri’s artistic project, and the company he founded in 1983, is that it is truly a family affair: the five dancers are his wife and children. The live, sleep, eat and work together daily in intense isolation crafting dances of elemental power and uncommon dynamism through an intensely intimate process.

The work features a trio of gloriously powerful women who exhibit strength of body and will in the earthbound manner they dive into movement, oozing into deep plie like squats and then pounding the taut canvas of their stretched red pants like drummers. Moments later they spring forth from deep lunges, pouncing then retreating, only to strike out again. The hour-long work is filled with mystery and mundanity: dancers carry plates and cups back and forth from a tea cart, rattling the china in percussive polyrhythms, and one woman sits in a chair and keens, rocking and hugging herself for an inconsolable loss. Later the women pass and stack plates around a wooden table with an urgency and assembly-line precision that brings new meaning to the term woman’s work. The one thin boy/man in the group attacks and retreats with preternatural grace, sometimes part of this female-dominated social structure, other times apart – an outcast or loner. And throughout amid the bustle, the urgent calls, the unmitigated pain and sense of loss, there remains a stunning impression of yearning, of hope. The ancient rituals of home and hearth, of work and rest, of group and individual it seems are drawn from a language and way of life that Mefri sees disappearing. Quickly evident in this riveting evening is how Mefri and his family can communicate so deeply to the heart and soul in ways that strike at the core, of unspoken truths about family, community and cultural continuity and conveyance.

One final note of continuity and cultural conveyance was struck resoundingly in December with Chicago Human Rhythm Project’s “Juba: Masters of Tap and Percussive Dance” at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. While the program was long on youth and short on masters – an indication that we’ve reached the end our last generation of true tap masters — Dianne “Lady Di” Walker represented the early tap revival providing the link to old time rhythm tap of the early and mid-20th century. The program, emceed and curated by Lane Alexander of CHRP, brought together a bevy of youthful dance companies, among them Michelle Dorrance’s Dorrance Dance with an interesting excerpt for two barefoot modern dancers and a tapper. D.C. favorite Step Afrika! brought down the first act curtain with its heart-raising rhythms and body slapping percussion. And, closing out the evening, Walker served up “Softly As the Morning Sunrise,” a number as smooth and bubbly as glass of Cristal, her footwork as fast as hummingbird wings, her physics-defying feet emitting more sounds than the eye could see. This full evening of tap also included Derik Grant, Sam Weber, and younger pros Jason Janas, Chris Broughton, Connor Kelley, Jumaane Taylor, Joseph Monroe Webb and Kyle Wildner. The evening with its teen and college aged dancers sounded a note that tap will continue to be a force to reckon with in the 21st century. That it occurred on a main stage at the Kennedy Center was – still – a rarity. Let’s hope the success of this evening will lead to more forays into vernacular and percussive dance forms at the nation’s performing arts center. The clusters of tap fans young and old gathered in the lobby after the show couldn’t bear to leave. If they had thrown down a wooden tap floor on the red carpeting, no doubt folks would have stayed for another hour of tap challenges right there in the lobby.

***

And I can’t forget a final, very personal experience. During the annual Kennedy Center run of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in February, I found myself pulled from my aisle seat to join the dancers onstage in Ohad Naharin’s “Minus 16,” which the company had just added to its repertory in late 2011. Clad in slim fitting business suits and stark white shirts, the dancers make their way to the lip of the stage and stare. The next thing you know, they’re stalking the aisles, climbing over seats, crawling across laps to bring up randomly selected members of the audience. The sequence is fascinating – a mix of the mundane, the ridiculous and the dancerly – inviting in the human element as these god-like dancers canoodle, slow dance, cha-cha and indulge their new-found partners. Soon they corral the group, circle, and in ones and twos the dancers begin to lead the participants off stage, leaving just one – most frequently a woman – standing in the embrace of her partner as the others hug themselves in a smug slow dance. On cue the dancers fall. The woman remains alone, in the spotlight. Frequently aghast, embarrassed, she slinks away.

Dreamlike is the best way I can describe the experience. Audience members seem to be selected according to a particular color, most frequently red judging from the previous times I’ve seen the work. As a “winter” on the color chart, I, of course, frequently wear red from my beret to my purse to a closet full of sweaters and blouses. When the dancers lined up, I felt one made eye contact with me right away. I didn’t avert my gaze and I thought that I could be chosen. But as they came into the audience, he passed me by and I exhaled slightly, relieved not to be selected. The stage re-filled with dancers and their unwitting partners as I watched. Suddenly, the same dancer who caught my eye was at my side beckoning, pulling me from my seat. My hand in his I followed him down the dark aisle and up the stairs. There the music changed frequently from kitschy ‘60s pop to rumba, cha cha, and tango – all recognizably familiar, a Naharin trait. Yet the choreographer definitely wants to keep the novices off guard, which is disconcerting because there are moments when the dancers are completely with you and you feel comfortably in their care, then they leave you to your own devices and all bets are off.

I realized quickly that I had to focus fully on my partner and not get distracted by what others on stage or in the audience were doing. We maintained eye contact throughout and went through a bevy of pop-ish dances: I recall bouncing, lunging, throwing in a bump or two and a great tango – wow, what a lead. Then they mixed things up, pushing all the civilians into a circle then a clump before reshuffling things. Somehow I came out with a new partner and things really heated up as I followed him and he me. I felt my old contact skills tingling back to life as I tried to give as good as he gave. He dipped me and I suspect that when he felt I gave in to it, he realized he could take me further. I don’t know how, but I found myself lifted above his head in what felt like a press. As he turned, I thought I might as well take advantage of this. I’m never going to be in the arms of an Ailey dancer again. I put one leg in passe, straightened the other, threw my head back and lifted my sternum, while keeping one hand on my head so my beret wouldn’t fly. He likely only made two or three rotations, but in my mind it felt like a carnival carousel: incredible. Back on earth with my feet on solid footing, he tangoed and embraced me. I knew what was coming. The slow dance when they lead partners off stage. I realized I might was well give in to the moment, I melted into his embrace and we swayed. Two bodies as one. Eyes closed. I momentarily opened them when I sensed the stage emptying. The only words spoken between us are when I said, “uh oh.” He squeezed me and then dropped to the floor in an X with the remaining Ailey dancers. There I was. Alone. Center stage in the Kennedy Center Opera House. I have been seeing performances there since I was a child in 1970s. I had seconds to decide what I was going to do. “%^&#) it,” I said to myself. “I’m standing here in the Opera House with 2,500 people looking at me. I’m going to take my bow.” I moved my leg into B+, opened my arms with a flourish, dropped my head and shoulders and rose, relishing the moment for all it was worth. Seconds later, the audience roared. I was stunned. I made my way gingerly off stage, still blinded by the spotlights as I fumbled up the aisle to find my seat.

Dreamlike. Throughout I knew this was something I would want to relish and remember and tried to find markers for while maintaining the presence of the moment. I was able to find out who the dancers were (yes, there were two) who partnered me. But I believe that Naharin wants the mystery to remain both for the onlookers and the participants. At intermission people were asking if I was a “plant,” insisting that I must have known what to do in advance. But, no, Naharin wants that indeterminacy, that edginess, that moment of frisson, when the audience realizes that with folks just like them on stage, all bets are off on what could happen. While we often attend dance performances to see heightened, better, more beautiful and more physically fit and skilled versions of ourselves (one of the reasons, I think, that we also watch football, basketball and the like), there’s something about seeing someone just like you or me up on stage. If the middle aged mom who needs to get the kids off to school then go to work the next morning can have such a rarified experience then maybe, just maybe, the rest of us can rediscover something fresh, untried, daring, out of sorts, amid the banality of our everyday lives. In this brief segment – and I couldn’t tell you how long it lasted, but I’m sure not more than five minutes at most – Naharin, through the heightened skill and beauty of professional dancers, offers escape from the ordinary. Audiences live through it vicariously by seeing one of their own up there on stage. For me the experience was unforgetable.

© 2012 Lisa Traiger

Published December 30, 2012

leave a comment