New Season: New Hope?

District Choreographer’s Dance Festival

Dance Place, presented at Edgewood Arts Center, Brookland Arts Space Lofts Studio, Dance Place Arts Park, Dance Place roof, offices, and Cafritz Foundation Theater

Choreography: Kyoko Fujimoto, Dache Green, Claire Alrich, Shannon Quinn of ReVision Dance Company, Gerson Lanza, Malik Burnett, and Colette Krogol, and Matt Reeves of Orange Grove Dance.

Washington, D.C.

September 9 – 10, 2023

When Dance Place opened its season each September, it heralded a surfeit of dance performances for the next 11 months. In fact, the nationally known presenter for decades offered up live dance performances across genres from modern to African forms, tap, bharata natyam (a classical Indian form), hip hop, flamenco, performance art, post-modern, raks sharki (belly dance), salsa rueda, stepping, even contemporary ballet, to mention just a few. Dance lovers could be assured of a show nearly every weekend of the year from September through June, with a smattering of performance options spread across the summer. Most years during its heyday, Dance Place presented between 35 and 45 weeks of dance annually, from both regional companies and national and international artists. Among those were first D.C. performances (pre–Kennedy Center invitations) from David Parsons Dance, Urban Bush Women, Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, Rennie Harris/Puremovement, Blue Man Group, and dozens of others. And along with well-curated programming, the organization offered professional and recreational studio classes in modern dance, West African dance and other forms, and a free summer arts camp for neighborhood children.

The feat, presenting more dance annually than the Kennedy Center, happened under the indefatigable visionary leadership of founding director Carla Perlo and her co-director Deborah Riley. Since they stepped away from leadership in 2017, the nationally renowned organization has struggled to find its new identity under two different artistic directors, an acting director, a global pandemic, and presently little institutional knowledge regarding the organization’s outsized influence in the dance world.

But season openings always offer a fresh opportunity to hope.

The 2023/24 season marks Dance Place’s 44th year. September 9 and 10, the organization chose to continue a tradition of showcasing locally based artists in new and recent works, which dates back to the Perlo and Riley era, and “post-pandemic” Christopher K. Morgan named the season opener the District Choreographer’s Dance Festival. This year, Dance Place and seven choreographic artists showcased not only their works but also the studio, performance, and space assets the organization manages and has access to along 8th Street NE, hard by the Metro and railroad tracks, just a short walk from Catholic University.

The afternoon began at Edgewood Arts Center, a community room used for weddings, parties, classes, and the like. Choreographer Kyoko Fujimoto, who also holds a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, fashioned a contemporary ballet quartet featuring point work and lifts, punctuated by the angularity of 90-degree elbows and knees — perhaps an ever-so-slight nod to Balanchine’s mid-20th-century neo-classicism. The work, “into the fields,” was meant to recall the experience of a medical MRI. That was evident in the horizontal crossings of single dancers rising and falling like pointed peaks and valleys of a heart monitor readout. It could also be heard in Caroline Shaw’s music from “Plan & Elevation” and another musical sequence from V. Andrew Stenger and Fujimoto. The stark black biker shorts and white tops provided an ascetic look for dancers Sara Bradna, Ian Edwards, Max Maisey, and Sophia Sheahan.

The audience was then led down the street to a Brookland Arts Space Loft studio for performer/choreographer Dache Green’s “Evolution(ary).” In the tight, bare studio, Green, long, lean and powerful, struts forward in chunky black heels, jean shorts, and an olive green trench coat. Viola Davis’ resonant voice is heard in her famous 2018 speech for Glamour magazine: “I’m not perfect. Sometimes I don’t feel pretty. Sometimes I don’t want to slay dragons … the dragon I’m slaying is myself …” To that, and then to a Beyonce-heavy score — “I’m That Girl,” “Church Girl,” “Thick,” “All Up in Your Mind,” peppered with other artists like Kentheman, Inayah Lamis, and Annie Lennox and the Eurhythmics — Green grabs center stage like a model on a catwalk, owning the space and moment as he poses, struts, bumps and grinds, vogues and twerks, all the while lip-syncing. It’s a public and private confessional about discovering and owning one’s personal story with power and self-love, acceptance, and being fierce.

Back outside in the partly cloudy afternoon, if one didn’t look up, you’d miss ReVision Dance Company’s Amber Lucia Chabus and Chloe Conway, clad neck to ankle to fingertips in highlighter pink and highlighter green respectively, poking a jazz hand, leg, or foot out from the Dance Place Roof. Choreographer Shannon Quinn let her two dancers loose on the roof to play with each other and with the viewers two stories below. I recalled film and photos of choreographer Trisha Brown’s 1971 “Roof Piece” and loved this nameless piece d’occasion all the more for its nod to post-modern dance history, while not taking itself too seriously, including playful moments and silly mime as the duo stepped down to disappear, then pop up seconds later in another location.

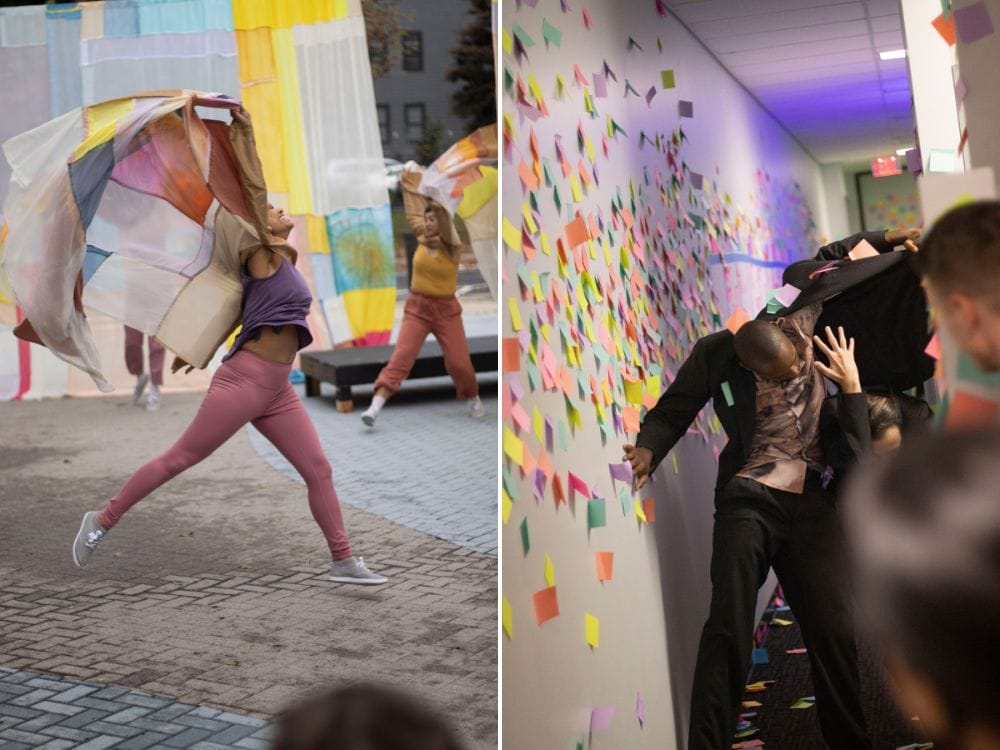

Claire Alrich’s “scenes from an elevator ascending” spread out on the Arts Park, a former city easement of land Perlo developed into a multi-use space for the community to congregate between Brookland Arts Lofts and Dance Place. With a set of stitched-together curtain-like panels and flowing cape-like tunics in mauve, mustard, and cantaloupe colors designed by Alrich and Mara Menahan, the three dancers stretch their arms to work the expanse of the costume. The work feels like an organic transformation in process. I was reminded of the caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly cycle, particularly as the dancers gently left the space walking away down Kearny Street as Santiago Quintana’s score faded.

“Paper Jungle” was meant to be a ten-minute experiential piece for ten people at a time to walk through the upstairs office cubicles of Dance Place. Technical delays kept groups waiting, but Orange Grove Dance, helmed by choreographic and design partners Colette Krogol and Matt Reeves, is consistently worth a wait. Entering the tightly constricted hallway, walls scattered with Post-it notes, “Paper Jungle” featured dancers Robert Rubama and London Brison joined by Reeves, who at times carried an open laptop on record. Audiences waiting in the downstairs lobby could watch — spy — on happenings upstairs on the large multi-picture video screen. Three men clad in slim black suits unfurled muscular, manic motion exploding along the cubicle corridor with bursts as legs and arms flung akimbo. The pressure cooker feeling of too much paper, too much movement, too many people, and sounds in the constrained space felt like a bad day at the office. Musicians Daniel Frankhuizen on cello and synthesizer and Jo Palmer on percussion compounded the atmosphere. “Paper Jungle” resonates with the overstimulated workloads and life loads so many carry, but, even so, with so much to see in such a short time span, it was hard to depart.

After a break the evening included two solos in the Dance Place Theater: percussive tap dancer Gerson Lanza’s “La Migra” explored his Honduran roots and emigration journey, while Malik Burnett’s “In Here Is Where We’ll Dwell” tackled his personal spiritual journey. Both works were personal testimonies to triumph over adversity. Lanza built on ancestral connections to traditional Africanist footwork in bare feet on an amplified wood tap board, pounding out syncopated bass and treble notes before donning brown leather tap boots for a soliloquy in sound. Burnett entered from the lobby hooded — a monk’s robe or a hoodie, in the half-darkness it’s both. Video clips draw on celebrated inspirational personalities from Oprah Winfrey to Amanda Gorman, Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, while the dancer draws himself out to expansive reaches highlighting a spiritual sense of striving for redemption. The work concludes with a slow walk upstairs through the audience to a fading light.

The festival format program, which began at 4:00 p.m., ran through about 5:30 p.m. with a break before the final two works went up in the theater, finishing up shortly after 8:00 p.m. For dance adventurers and dance lovers, this was full immersion; others may not have been so satisfied.

Finally, while this District Choreographer’s Dance Festival heralds a new season, Dance Place’s programming remains truncated. Some months contain just a single run and later in the season multiple weeks are booked, with most presentations being for a single performance rather than a two-show weekend. The organization suffered multiple blows with the retirements of its founding leadership, and turnover in its replacements, along with the ongoing challenges of the pandemic and post-pandemic recovery. Six years along, Dance Place is still finding its footing. It may never be the same. We can only hope the new leadership team remains committed to building on past successes and supporting dance and dancers for generations to come.

This review originally appeared September 13, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Romp and Rumination

Choreographer Sarah Beth Oppenheim scales a moving and storage warehouse

‘Many Extra Only More’

Heart Stück Bernie

Extra Space Storage, 2800 8th Street NE

presented by Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

July 7-8, 2023

By Lisa Traiger

It’s been a while — a long while — since I saw a locally produced, original choreographic work that wowed me. Saturday night July 8, 2023, I was wowed. As I sat on the Franklin Street NE bridge pedestrian walkway, facing the rectangular industrial Extra Space Storage building on 8th Street, waiting for the sun to set, I donned “silent disco” headphones and bobbed my head to the beat. The music, edited by Oliver Mertz, ranged from Bela Bartok to Ethiopian musician Mulatu Astatke to pop band Animal Collective and Ukrainian group DakhaBrakha to name a few of the eclectic choices. Traffic whizzed by on the bridge, leftover illegal fireworks boomed in the distance, a siren screamed, and on railroad tracks parallel to 8th Street, trains rumbled by.

As the sky darkened, the 20 windows of Extra Space Storage brightened, then music pumping, at once 40 dancers filled the 4 x 5 grid of windows, bopping in brightly colored separates of red, yellow, and orange. Many Extra Only More unfurled as a massive and wow-inducing site-specific piece from the marvelously imaginative and generative mind of Silver Spring–based choreographer Sarah Beth Oppenheim, who leads ten fearless dancers of her company Heart Stück Bernie. Many Extra Only More begins like a romp. You can’t help but smile and wish you were up there dancing with them.

But there they are, each in a separate window box, brightly lit, smiling. Together and alone. And soon the primary colors and vivid playfulness, quirky, tick-like gestures and poses, take on moodier shadings. It’s not so long ago, as memory serves, we were all living in and in front of computer-lit boxes, isolated in our homes but distantly together in our Zoom rooms at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Oppenheim’s choreography does those quick tone shifts often, and well. She’ll make a ridiculously cute set out of cardboard cut-out shapes — oversized paper-doll dresses, puffy armchairs, yellow suns and crescent moons, rainbows and stars — or reams of paper with childlike drawings or PowerPoint-like instructions for the audience. She crafts as if Martha Stewart taught kindergarten and her dances emote an unspoken language filled with silent action verbs; dancers skip and hop, slink and saunter, shimmy and slither, ooze and vibrate, twitch and punch, bounce and breathe. Oppenheim has some of the quirky bright cheerfulness along with the millennial zeitgeist of sitcom actress and musician Zooey Deschanel that belie her own bright smile and vivid thrift store wardrobe.

Oppenheim has been an artist-in-residence at Dance Place — the producer of this outsized, and outside, evening — and has presented work on its stage. Her choreography has also been seen in gardens and galleries — including the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing — alleyways and storage closets. She sees dance in life’s most ordinary moments and elevates those mundanities with movement and visions of how living and dancing deeply intertwine. Her work in the community with its light and dark tones and its serious fun is her way of spreading the gospel of creative thinking to the masses.

Saturday night Many Extra Only More addressed multiple ideas in its 50 fast-moving minutes. Audiences had to come to terms with the caveat that they wouldn’t see everything. A pre-show announcement noted that no spot would allow viewers to see it all completely, and they were welcome to move around throughout the show. Sitting on what I believed were prime “balcony seats” on the Franklin Street NE bridge made me wish I was below, across the street at the Dewdrop Inn looking head-on at the dancers filling the windows. But I was quickly reminded of Merce Cunningham’s Events where dancers populated public spaces and you couldn’t catch it all, intentionally. Oppenheim’s work also nodded to another mid-20th-century modern dance choreographer, Anna Sokolow, whose acclaimed Rooms explored the isolation individuals felt in their massive apartment buildings: living in tight clusters, but each alone in their singular rooms. Marcel Duchamp’s readymades — found objects displayed as art — also came to mind with the readymade non-theatrical setting and set pieces — ordinary stuff you would find in a storage unit. Or maybe that’s a nod to the hit show Storage Wars. No matter, Oppenheim knows what she’s doing at every moment of this large-scale romp and rumination.

Many Extra Only More spooled out episodically in those window frames, vertically, horizontally, diagonally, and randomly. Oppenheim — with rehearsal assistance from Nancy Bannon and Kourtney Ginn — realized a choreographic feat in spatial organization navigating the windows like a Rubik’s cube master. Dancers shifted in groups, individuals, sometimes carrying in props, crafty cutouts, even at one point a striped sofa. Lighting by Kelly Colburn and Mark Costello used colored gels on the intense fluorescent warehouse lights, among other large-scale tricks, to shift mood and tone during the vignette-like sequences.

Moments of group synchronicity — even as dancers eschewed complete unison — conveyed celebration; a series of folk-dance–like chains and circles reminded me of a wedding or bar mitzvah. Then smaller configurations of two, three, or five reflected relational and interactive conversational moments. One dancer — Sadie Leigh — donned a green striped robe — like the green garage-like doors of the storage units — on which a collection of paper cutouts of overflow detritus were pinned: a lamp, a chair, an end table, a candlestick. Metaphorically, the choreographic structure with this oversized cast reflects the overstuffed lives so many Americans live today — homes filled with too many dishes, toys, books, sofas, and lamps, and not enough Marie Kondo self-reflection to discard what isn’t joyful. Instead, those excesses of our lives, which we can’t let go of, become a boon for the storage industry. And a reflection of the baggage we hang on to.

This is seen in moodier sections of confrontation, dancers battling as we watch — becoming voyeurs looking in from the outside. A song comes on with a violent thread as slow-motion fists and clawed hands are drawn out. A woman is splayed across a table — others manipulate her. Across the way, two dancers run themselves into the windows, again and again. Suddenly, nothing is bright or fun, sunny or sweet. Cute sun and rainbow cutouts taped to windows can’t whitewash the discord and pain surfacing in this glass-housed world Oppenheim has wrought.

The mood modulates — like life — in shifting vignettes. We follow the dance modulate from joy to pain, playfulness to violence, happiness to despair — and, finally, at the end, back to another dance-off, each dancer in her window grooving to the beat, then departing a few at a time, only to reappear on the street in front of the warehouse. The earphones still blasting music, the disco still silent, but then everyone has clumped together, and some audience members join the group. If Oppenheim wished for a big, bold, extra, supersized statement piece about the simple yet profound ways dance affects us, changes us, makes us think, moves us, and makes us move, she did it.

In recent years, we’ve seen some tectonic shifts in dance in Washington, D.C., from the departure of MacArthur “genius” grantee Liz Lerman a dozen years ago, to the retirements of Dance Place co-directors Carla Perlo and Deborah Riley in 2017, to the departure of Septime Webre from the Washington Ballet that same year, and the recent untimely losses of Michele Ava, cofounder of Joy of Motion, and Melvin Deal, founder of African Heritage Dancers and Drummers. Just this year, the service organization Dance Metro D.C. closed down. Dance in the region has been on unsteady footing. Even before the pandemic shut down studios and companies for months and months, including some that didn’t survive, we were seeing fewer dance presentations in smaller venues beyond the Kennedy Center’s large stages. Dance Place’s once-weekly performance presentations have diminished to one to two performances a month.

This, Oppenheim’s largest and most complex work to date, was initially conceived in 2017, but delayed by that global pandemic. The complexities of the large working business site, technical requirements, and a massive cast for a locally produced dance company demonstrate that creative forces continue to percolate in D.C.’s homegrown dance community.

So Many Extra Only More bodes well for the future. Let’s hope Dance Place and the D.C. metropolitan dance community can take inspiration from Oppenheim’s extra-large, many-dancer production that shouts “More” with its collection of a strong cadre of young and veteran dancer/choreographer/creatives in its cast.

Featuring Heart Stück Bernie Dancers

Emily Ames, AK Blythe, Amber Lucia Chabus, Terra Cymek, Kate Folsom, Raeanna “Rae” Grey, Sadie Leigh, Patricia Mullaney-Loss, Nicole Sneed, Kristen Yeung

with

Claire Alrich, Katherine Berman, Lauren Bomgardner, Lauren Brown, Jennifer Cinicola, Sarah Coady, Annika Dodrill, Allison Grant, Safi Harriott, Jocelyn Hartman, Faryn Kelly, Betsy Loikow, Julia McWest, Bretton Mork, Simone Nasry, Annie Peterson, Sarah Raker, Jane Raleigh, Alison Waldman, Berea Whitley

and

Elizabeth Barton, Jadyn Brick, Annie Choudhury, Lauren DeVera, Celina Jaffe, Emilia Kawashima, Luisa Lynch, Chitra Subramanian, Zoe Wampler, and Janae Witcher

This review originally appeared July 10, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Love Is in the Air

The Look of Love

Mark Morris Dance Group

John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 26-29, 2022

By Lisa Traiger

One-time maverick choreographer Mark Morris is now mature enough to collect Social Security. In another millennium, way back in 1985, his Mark Morris Dance Group made its Kennedy Center debut upstairs in the Terrace Theater. Back then he had long brunette ringlets of curls, a sensitive and knowing ear for music, and a crafty way of interlacing modern dance with everything from Bach to country, East Indian raga to punk. And it worked. His young company of ten dancers exuberantly tackled the insouciant steps that were both smart and sly.

Since, Morris and his company have become institutions in the oft-precious modern dance world. He has been back to the Kennedy Center many, many times. Through Saturday, October 29, 2022, the company is ensconced at the Eisenhower with Morris’ newest piece, The Look of Love, an hour-and-change work set to 1960s and ’70s pop icon Burt Bacharach’s hits.

The Look of Love comes on the heels of the company’s last Kennedy Center show in 2019, when it brought Pepperland, an easy-listening, brightly colored homage to the Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. Back in ’85 at his first DC program, the company danced to Vivaldi, Bach, and the Violent Femmes. Nothing was experimental, but it all felt fresh, performed with frisson. Morris’ recent forays into baby boomer songbooks align well with the Broadway retreads of jukebox musicals.

Morris’ followers know well his facility with musicality and his requirement to always use live music. At the Eisenhower Theater, the company music ensemble featured music arranger and long-time MMDG collaborator Ethan Iverson on piano, and gorgeous-voiced Marcy Harriell rendering Bacharach’s songs — with most lyrics by Hal David — in thoughtful jazz renditions, with backup vocals by Clinton Curtis and Blaire Reinhard, joined by Jonathan Finlayson on trumpet, Simon Willson on bass, Vinnie Sperrazza on drums. The ensemble plays in the elevated orchestra pit, and Harriell, glamorous in her bare-shouldered dress, often turns to sing to the dancers on stage.

Raised in Forest Hills, New York, Bacharach, 94, attended the same high school as Simon and Garfunkle and Michael Landon. A child piano student, he favored jazz and later in California studied with mid-century modernist composers Henry Cowell, Bohuslav Martinu, and Darious Milhaud, whom he cites as his greatest influence. But it’s songs like “Alfie,” “I Say a Little Prayer,” “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” and “What the World Needs Now” that defined pop music for the 1960s and ’70s generation. Lively, singable stories of love, longing, loss, and connection, with an occasional shadow tossed in. Morris selected 14 indelible songs from the Bacharach songbook beginning with a jazzy instrumental riff on “Alfie” — surely many heard Dionne Warwick singing in their heads.

On the empty stage a few scattered folding chairs stand — one of the cliches of modern dance is the chair as a prop. It suggests the choreographer needs a device and that’s all that’s available in the rehearsal room.

The dancers enter to strains of the feel-good anthem “What the World Needs Now,” clad in sunny pastel tunics, shorts, pants, or dresses color blocked in melon-y orange, lime green, sunny yellow, ochre, and starburst pink. Morris is a master of manipulating simple movement patterns and weaving them into complex spatially shifting phrases. Fans of folk dance will recognize standard footwork featuring stomps, grapevine, and triplet steps in converging and separating lines and circular paths. Another favorite Morris-ism could be termed music visualization, when he has dancers imitate gestures that match the lyrics. It’s like he’s checking to see if we’re listening and watching enough to get his little “Easter eggs.” When the lyrics proclaim: “There are mountains and hillsides enough to climb,” in pairs, one dancer falls as another lifts an arm up — creating the base and peak of the mountain. Later, accompanying “There are sunbeams and moonbeams enough to shine,” one dancer pushes an arm upward with a one-footed hop on sun, the second follows in the other direction on moon as a raised arm indicates a moonbeam.

Next, to “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again,” on the phrase “What do you get when you kiss a guy? You get enough germs to catch pneumonia,” a little chase ensues before one dancer forces a sneeze on cue at pneumonia. Again and again, Morris has the dancers mimic the lyrics in ways that are easy, obvious, and cute. In my college choreography class this “Mickey Mousing” the music was denigrated as too simplistic. I think it’s become an easy go-to for Morris; it makes the audience feel that they “get” modern dance while letting them feel “smart.”

Morris is at his best at inventing and reshuffling dancers in evolving floor patterns here. With ten dancers moving in, shifting into duos and trios, or playing a soloist against the group his amiable locomotor walks, runs, skips, skitters, and leaps shuffle and reshuffle the landscape on stage. And all this patterning mostly jives with Bacharach’s jazzy, subtle syncopations that add interest to his standard 4/4 common time musicality.

In Harriell’s churchy rendition of “Don’t Make Me Over,” dancers flop and tumble, trying for quirky opposition, then punch a fist in the air. For “Always Something There to Remind Me,” the gesture of choice is pulling on, off, or straightening clothes, as if miming changing an outfit is enough to forget an old lover. For lovers, lost, found, wanted, and wanting are what Bacharach’s lyricist pens so adeptly.

One oddity, “The Blob,” features a dissonant clatter of horns, drums, and piano as the dancers clump together in a pile-up of chairs and limbs against Nicole Pearce’s eerie, blood-red lighting on the backdrop. At first, I thought this creepy start would morph into “What’s New Pussycat?” But, no, a quick Google search told me Bacharach actually composed the film music, and theme song, for the 1958 film The Blob. And that’s what happened: they created a blob of bodies and chairs before moving on.

The evening song cycle concluded with “I Say a Little Prayer,” and here Morris brought the company full circle, returning dancers to the opening circle, as they intersect in a bit of a basket weave. Some now-expected goofy movements — dancers’ arms flapping like wings of graceless angels, as they parse out a pony-like bounce — garner a laugh or two. Then a lexicon of the gestural motifs is recapitulated as the company, two-by-two, one-by-one, makes their way off stage, leaving a lone dancer to exit. The Look of Love ends not on a high note, a bright note, or even a grace note, but on a breathy “Amen.” It’s like a sigh — of relief, of longing, of completion, perhaps. But it feels inadequate, even incomplete.

Throughout, the dancers adeptly work through Morris’ signature paces, but for the most part, they don’t project any particular deep feeling to the movement, the music, or even one another. Sometimes they were just going through their paces rather than reveling in the music visualizations. It’s as if they’re still looking — for inspiration, for ways to fully love and embrace this new work. And it’s a shame because the musicianship of the ensemble should draw these dancers in, but they haven’t fully committed themselves to loving The Look of Love.

This review originally appeared on DC Theater Arts on October 29, 2022, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2022 Lisa Traiger

Holding

And Now, Hold Me

Directed and choreographed by Britta Joy Peterson,

with performance and movement collaboration by Sergio Guerra Abril and Dylan Lambert

Dance Place

Washington, D.C.

January 22-23, 2022

By Lisa Traiger

Choreographer and ardent collaborator Britta Joy Peterson has been creating dance, video, and performance pieces in the Washington, DC, region since 2016, when she took a position as a professorial lecturer at American University in the District.

Her newest piece, And Now, Hold Me, is part of a trilogy Peterson began work on in 2014 or ’15, she said after Saturday evening’s program at Dance Place. Each work — including “Vinegar Spirit,” which came to Dance Place in January 2019 — wrestles with time and space in intentional ways to tease out philosophical and phenomenological concepts in a kinetic palette. What’s most interesting about this triptych of pieces is Peterson’s keen focus on space and how the introduction of bodies moving through it changes, literally, everything — the architecture, the meaning, the temperature, the feeling, even the air in the room reshapes itself. For And Now, Hold Me, a duet, the space designed by Elsa Rinde creates a stage within a stage demarcated by white PVC pipes slanted like a giant soccer goal framing the performers, with a white floor floating in the larger surrounding black void.

Two men, sharply dressed in wool coats, neat sweaters, slacks, and shoes, sit cross-legged on the floor looking like schoolboys awaiting roll call. “In the beginning … and now,” one intones. Then a monologue spoken in succession by both men, but not to one another, pours forth, in poetically Biblical cadences about flesh and how it’s in and of the world, the stuff of life, it provides a way of perceiving and making meaning. “Through flesh,” one says, “I know you.” Still seated, they twist, bend, windshield-wiper their knees, gesture in perfectly intricate unison and a low thrum of sound crescendos. Like twin brothers they rise and begin to disrobe. A shift in Evan Anderson’s lights transforms the backdrop, which appeared as colorful and white vertical blinds, into a loosely woven web of multicolored ribbon, which streams from a giant spool at the side of the stage. Dancer Dylan Lambert behind stage pulls ribbon from the endless spool and adds to the spidery tapestry.

Meanwhile, with slippery grace, Sergio Guerra Abril meanders between gestural brushes of his hair and loosely articulate twists, tumbles, balances that unwind and rewind, a manifestation of the unspooling ribbon. What becomes a series of episodes, silent playlets in a sense, is broken up by canned applause, when each performer pauses for an unironic bow. Guerra Abril dons a shimmery blouse, red go-go books, and a flouncy white skirt for a playful lipsync of “Desatame” by Monica Naranjo. His playful drag and voguing offer up a fantastic death drop — a split-second fall to the back, one leg sexily raised in the air.

Lambert then has his own bit of fun impersonation. Introduced by a few bars from Van Halen’s “Jump,” he enters with towel and yoga mat, converses with imagined gym rats about exercise, bitcoin, and dogecoin, all in perfect yoga-bro fashion.

An improvisational duet on expected feminine and masculine tropes allows the dancers to tweak social and cultural expectations of the alpha male and bitchy female. Guerra Abril reads from a series of shlocky blog posts that advise that men should “take up more space to look more powerful” while women should “avoid pain at all costs.” All the while they tumble, lift, balance one another on a hip or shoulder in an easygoing improvisation. On either side, sign language interpreters make this and all the spoken word accessible.

As the work winds down, strains of Liszt’s dreamy “Liebestraum No. 3” build, shifting the demeanor of the space that has contained so many moments of bodies moving and filling the void, light painting over the darkness, architecture delineating the blank stage canvas. The two men begin packing up the clothing and props; the woven spidery tapestry, their own words and phrases, parsed out over the course of nearly an hour have reached a quiet moment of intimacy. “And, now … the end” arrives, but, still, they’re not finished. There’s one more thing to do.

They stand and, finally, hug, body to body, flesh to flesh. Two become one. Space and time have contracted and exploded. While And Now, Hold Me is absolutely not a “pandemic piece,” this moment of coming together resonated in a world where many people have not hugged or been hugged for nearly two years now as the ongoing challenges of isolation and quarantine continue to hold some hostage to COVID-19 and its variants. Peterson’s work meditates on time and space, with moments of moving beauty, irony, fun, and, finally, a thoughtful confluence of bodies and flesh. I’ve avoided writing on her work until now because I hadn’t found enough in it that appealed to me. In And Now, Hold Me, I discovered much that spoke to me, particularly through the exquisite performances of Abril and Lambert, as well as the finely conceived structure and expert production of Peterson’s artistic and advisory team. I’m glad I returned to her work to discover a deeply conceptual study of what it means to move and take up space. A solo dancer on stage evokes an individual’s world, but Peterson shows us that two people sharing space create a universe of possibilities.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts on January 24, 2022, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2022 Lisa Traiger

From Mercy to Grace

Ronald K. Brown/EVIDENCE

featuring “Mercy,” “The Equality of Night and Day: First Glimpse,” and “Grace”

Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 21, 2021

By Lisa Traiger

Choreographer Ronald K. Brown is the dance world’s preeminent preacher. His works — exquisitely performed Thursday (through Saturday) evening at the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater — open the heart and lift the soul. EVIDENCE, the company he founded in 1985 in Brooklyn, gives voice to the cultural legacies and experiences of the African American community. The rich triptych of works, which spanned two decades, took the audience on a spiritual journey, accompanied by the historical underpinnings of the African American experience.

Like a semiotician, Brown imbues his choreography with gestures, structures, postures, signs, and signifiers that embody the Black experience. There’s the grounded way his dancers walk and stand, knees juicy as they give in and rebound to gravity’s pull, while their upper bodies pronounce themselves as unselfconsciously powerful and graceful. And then the torso, spine, and shoulders that undulate in a subtle acknowledgment, again, of the natural energies land, sea, and air written into our bodies.

Brown fashions his movement language with a complement of subtly semaphoric gestures that convey meaning — clenched fists, the dap or single raised fist, raised praising arms, arms up as if under arrest, and hand held at heart center. These and others become a revelatory vocabulary across the evening’s three works, without becoming mimetically obvious.

“Mercy” featured the accompaniment of Meshell Ndegeocello’s genre-slashing funk/soul/jazz/hip hop in a spare and contemplative score that shifts from meditative to a heavier rock beat allow the company of dancers to unfurl from simple walking to full-bodied tilts, bird-like arms in precarious balances, and whipping spins. The lighting by Tsubasa Kamei here is moody but a series of glowing fabric columns dispersed across the stage that hide and reveal the dancers lend a temple-like feel to the work.

Yet the dancers enter walking backward, as if the world has turned upside down. In fact, it has. As the piece progresses the six women and five men navigate the space in quick-footed shuffles and effortless ease. At one moment, the men tumble to the floor as the women continue dancing; at another, there’s a freeze-frame hands-up/don’t-shoot gesture. The reality of our nation’s divisions and sins is embedded in the dance. A priestess-like figure, clad in a regal woven headdress and the elegant deep brown gorgeously draped fabrics of costumer Omotayo Wunmi Olaiya, leaves the community for a solo that suggests compassion and healing drawing on Africanist movement vocabulary, rolling shoulders, undulating spines, winging arms and bent-knee steps. Deep-voiced Ndegeocello (who, by the way, studied at Oxon Hill High School and Duke Ellington School for the Arts as a teen) chants aphoristic phrases — “Have mercy on you,” “As you think, so shall you become,” “I’m at the mercy of the shifting sea” — as a prayer of healing.

Created this year, “The Equality of Night and Day: First Glimpse” features a score by Jason Moran and recorded clips of speeches from racial justice activist Angela Davis. While still a work-in-progress, the piece is well on its way to a full artistic statement. Dancers clad in rich blue choir-like robes suggest a movement choir in the way they circle, gather, and realign themselves to Moran’s jazzy, bluesy accompaniment. And this group-think construction becomes fitting, as we hear Davis questioning America’s democratic values and actions that she says “spawn terror.” “How,” she asks, “do we imagine democracy that doesn’t thrive on racism, homophobia, capitalism … [how do we] use our imagination to come up with new models of democracy.” The dancers appear in a Sisyphean struggle, then at moments they tremble, as if terrorized or exhausted. But the most powerful and lasting vision here is of simplicity: In a quiet moment as the dancers walk, circling up in a steady understated but regal gait. They shed their robes, neatly place them at the circle’s center, and become an offering.

Brown’s signature work, “Grace,” now two decades old, remains as fresh as it did in its earliest rendition by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Under golden sunny lights against a hot-red background, the white-clad dancers driving speed, shuffling quick-footed patters, space gulping leaps, and rolling spines from bent waists unfold over a pulsing beat, first churchy then jazzy and groovy. The incessant drive that binds these dancers as they expend every ounce of muscle, sinew, and bone to the utmost becomes the perfect way to elevate this program of faith-infused works. The trajectory Brown carves tracks from the brooding over our nation’s state of societal dysfunction and prejudice and how to heal in “Mercy” to a call for action in “The Equality of Night and Day,” and reaches its apotheosis and, ultimately, a state of praise and blessing in “Grace.”

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts on October 26, 2021, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2021 Lisa Traiger

Paul Taylor Dance Company Re-Opens Kennedy Center Dance Season with Verve

Familiar works ease us back into the theater on a high note.

Paul Taylor Dance Company

Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 7, 2021

By Lisa Traiger

At this moment, as the nation toggles between light and dark, hope and despair, there was no better choreographer to turn to for the Kennedy Center to inaugurate its 2021–22 (fingers crossed!) dance season. The Paul Taylor Dance Company, founded by the maverick choreographer in 1954, remains an iconic American legacy company. Taylor, who had some DC roots, would sometimes reminisce to me about growing up on Connecticut Avenue, near the National Zoo, and once he regaled me with a tale of peacocks escaping.

The creator of almost 150 choreographic works, Taylor died in 2018, passing on leadership in the company to a former Taylor dancer Michael Novak. In recent years the company, under Novak’s artistic direction, has invited in other American choreographers to share their aesthetic. But this first live program back, after 18 months of Zoom and virtual performances, homed in on two seminal Taylor works:

“Esplanade,” the mostly playful romp, set to Bach’s Violin Concerto in E Major, that the choreographer made as an experiment in 1975. He challenged himself to not use a single “dance” step, relying solely on pedestrian movement, although elevated by the impeccably trained dancers performing the runs, walks, skips, jumps, grapevines, dashes, and crawls as the dancers converge, separate, and regroup at breakneck speed during the allegro.

A master of modulating moods, “Esplanade” serves as a Taylor primer in interweaving light, free-for-all fun with a darker, more contemplative middle section, the largo section of Bach’s Double Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor. Here, the sunny outdoorsy-feeling spaciousness of the first movement contracts. A trio of dancers — two women, one dressed androgynously, reach and try to connect with a man, but a sense of disconnection and despair hangs over the darkened bare stage, while a fourth dancer, as if responding to an alarm, frantically circles this tightly knit trio that can’t reach out and touch one another. Perhaps it’s a family portrait of loss and broken promises.

But again, the music brightens and the playfulness resumes. Taylor’s dancers are beloved for their verve and ability to fall, tumble, and rebound with nary a misplaced bobble. The section where the nine dancers continually run, skip, dive, and tumble to the floor is always breath-catching — someone’s surely going to get hurt — audible gasps could be heard in the audience. But amid the chaos of flying leaps that slide like a runner into home plate, with these continuous falls to the floor, the enduring takeaway is that even as we stumble and fall, we don’t or shouldn’t stay down for long. The world is off-kilter, and has been for a long while, but we’re all still here, making the best in precarious situations. Interestingly, this company of young dancers carries themselves with more lightness and lift. The Taylor style during his lifetime displayed a weightier, more grounded feeling; this current company has just three dancers who have more than five years in the troupe. Most joined in 2017 or after, with the newest hires coming aboard in 2020 and 2021, when even amid the pandemic, virtual classes and rehearsals went on.

“Company B,” the opener, was commissioned by and premiered at the Kennedy Center 30 years ago, in a joint venture with Houston Ballet. I remember that program and the ballet’s dancers, too, had a lighter, lither approach to the Taylor style, but the piece, even with its energetic swing tempos, contains that Tayloresque moodiness, that toggling between light and dark, joy and sadness.

Set to the effervescent songs of the Andrews Sisters, who served as a soundtrack for a generation of American soldiers and civilians during World War II with bright bouncy rhythms and fun, cheesy rhymes. But, as well, there are darker moments and Taylor doesn’t wait for the wrenching war-separating-lovers lyrics. The opening Yiddish inflections of “Bei Mir Bist du Schon” captivate the dancers into a sprightly jitterbug, yet in the background, a silhouette of men slowly marches, kneels, aims rifles, and tumbles. This fore- and backgrounding serves as a perfect metaphor for the American experience of World War II — a war that was fought an ocean away, not on U.S. soil. Throughout “Company B,” that dichotomous sense of joy and sorrow intermingles on stage in foreground and background. There are impish solos and plenty of mugging in “Tico-Tico,” “Pennsylvania Polka,” and “Rum and Coca Cola.” And wrenching moments, too, in “I Can Dream, Can’t I?” featuring Christina Lynch Markham longing for her overseas beau, or in “There Will Never Be Another You” as Maria Ambrose mourns for her fallen lover Devon Louis.

“Company B” ends with a reprise of “Bei Mir Bist du Schon” that is darker, because Taylor reflects back America’s World War II history: that what was bright and flirty on the home front was not what was happening overseas, in Europe. Is the Yiddish song a tell, perhaps, for the Holocaust and Hitler’s extermination of 6 million Jews? Or is it a coincidence that Taylor opened and closed “Company B” with it? He was typically elliptical when discussing his dances, famously answering the question, “What’s the dance about?” with the rejoinder “Oh, 20 minutes.”

In the coming months and years, undoubtedly many artists will craft works that respond to our immediate crises — the global pandemic and racial reckoning. There will be time to ruminate and explore, but at this moment, the familiarity of a 20th-century master choreographer feels just right to ease us back into the theater on a high note.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts on October 9, 2021, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2021 Lisa Traiger

leave a comment