Past and Future Share Stage: Ailey Company’s ‘Revelations’ and ‘Lazarus’

By Lisa Traiger

A cough, a gasp, the sound of a heartbeat. A sudden flash in the darkness. These sounds and images begin “Lazarus,” the brand-new work from hip hop master Rennie Harris, which opened a glitzy celebration of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s 60th anniversary at the Kennedy Center Opera House. The roiling evening presented the company’s first two-part ballet – throughout his career, Ailey called his decidedly modern works ballets. The combination of “Lazarus” and the “blood memories” of “Revelations” took the well-heeled audience on a journey through the hard and heartless history of being black in the United States, where slavery and segregation remain our nation’s original sin. At the close, though the audience roared its approval, those first gasps and the searing images of suffering remain. And both are as integral to the Ailey essence as to our American tale.

Bathed in dim light by James Clotfelter, the Ailey dancers toggle between an exaggerated slow walk, a quick-footed buck-and-wing, and stark stillness. The dancers stand, their shoulders hunched over, heads drooping.

And suddenly, a vision of the “strange fruit” of lynched bodies hanging from poplar trees elicits a gasp, this time from knowing observers. This is how “Lazarus” works its magic: Harris maneuvers his shifting movement tableaux calling on embodied images of the wretchedness of being black in America. From the agonizing image of Eric Garner, cuffed and gasping for air, crying “I can’t breathe,” to snapshots of hunched bodies, doubled over from exhaustion, physical and spiritual, to the Hollywood-ized visions of a “happy Negro” singing and dancing for his supper, Harris has collected the visual atlas of the immoral subjugation of a people.

A Philadelphia native who grew up on the rough streets of North Philly, he has spent decades bringing vernacular street dance forms to concert stages around the world with his own renowned company, making hip hop theatrical and imbuing it with messages of despair and hope. Harris knows his history, of course, but he knows, too, how to capture in movement images the harsh and inscrutable essence of being black in America.

This is the heart and soul of “Lazarus,” which the Ailey company commissioned as a tribute to its founder, Mr. Ailey, who lives on through the choreography he gave his dancers and through a now powerhouse dance organization. The piece, too, serves as a rejoinder to Ailey’s own seminal choreography, “Revelations,” which takes viewers on a similar spiritual and historical journey from slavery to renewal to revival in its three well-known sections.

“Revelations” has been the company’s bread-and-butter for decades, enticing audiences in for the reverence of this finale, and giving them a swath of newer works that toggle between contemporary modern dance, curated by current artistic director Robert Battle, and Ailey classics, some still resonant, others a bit faded. The much-admired company’s 60-year history can, in part, be attributed to the popularity and influence of “Revelations,” which sparks whoops, nods and clap-alongs for the familiar gospel songs and spirit-infused dancing entrances audiences year after year. Akin to ballet classics like Swan Lake, “Revelations,” it seems, never gets old. Alas, it is not always expertly performed. Opening night, it felt a little subdued coming right after the far heavier dramatic arc that “Lazarus” rides. Perhaps the dancers were spent after throwing down their hypersensitive and kinetic performance of the two-parter.

When seen next to “Lazarus,” with its far more trenchant — and realistic — look at the African-American experience, “Revelations” feels more than a little old-fashioned. The near-ancient Graham technique — contractions of the pelvis as the back curves, either smoothly or percussively, lateral side tilts, and running triplet steps — looks quaint next to Harris’s more sophisticated fusion of street dance coupled with modern techniques and gestural references.

That’s not to say Ailey’s masterwork should be retired. To the contrary, the two works serve as instructive companion pieces when seen together. In fact, Harris is filtering Aileyisms into the work right alongside his sly references to the Dougie, the Nae Nae, and the Dab. In “Lazarus,” Harris seems to be wrestling to uncover not just Ailey, the choreographer, but Ailey the man, who put his heart and soul into his choreographic ventures and navigating the world as a black man amid the peak of the Civil Rights movement and into the 1970s and ‘80s.

In “Lazarus,” Harris, like Ailey before him, alludes to Biblical elements. The story goes that though dead for four days, Jesus resurrects Lazarus, the miracle foreshadowing the resurrection of Jesus in the New Testament. In “Lazarus,” though, the struggle, the agony of oppression, is told in grim, gritty segments of movement montages. A group of women harvest an invisible crop, drawing sustenance from the earth, tucking it into their bundled aprons. Another clump of dancers falls to their knees, hands clasped in prayer, trembling — for salvation from God or man? Bare-chested men, their pants held up with a cord of rope, collapse, others drag these lifeless bodies off stage.

Harris shows us the burden of history, the weight of living — and dying — black in America. The piercing cries — ululations — punctuate Darrin Ross’s wide-ranging score, along with other equally harsh sound effects including gunshots, screams, and weeping. This first part of “Lazarus” pushes viewers beyond the dichotomous earth-and-heaven pull of Ailey’s first sections of “Revelations,” “Pilgrim of Sorrow.” Alas, in Ross’s sound score, the earlier voiceovers are almost indecipherable over pulsating underscoring. Some of the words are Ailey’s own, others are from Harris.

Harris takes the simplified slavery-to-freedom narrative of his progenitor and reflects on it with a more jaded 21st-century mindset. Harris doesn’t take us to the water, he takes us into the mud. As dancers lay prone, their arms undulating as so many rows of corn or wheat waving in a field, one dancer navigates through this thicket of bodies. That image ends part one and begins part two.

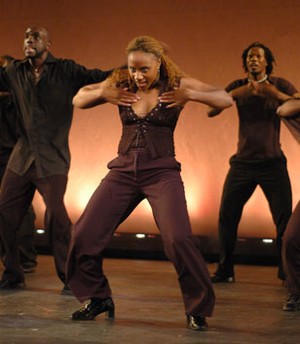

On their return, the dancers are no longer in early to mid-20th-century streetwear — A-lined skirts, slacks, overalls, or sweaters of muted earth tones. Their bare feet are now ensconced in black sneakers, while they’ve donned costume designer Mark Eric’s purple and burgundy club wear. The heaviness of Act 1 lifts with a song, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” as prone bodies rise from that reedy bog. Their hands beseech in prayer, and tremor with hope or trepidation. As drums pound out a samba-style beat, groups of dancers, first men, then women, catch the heat of the beat, heads bob, hips twitch, feet shuffle in swift kick ball changes. And as in all Harris works, the dance becomes a spirit-filled experience.

This is where Harris finds soul and purpose, letting the dancers loose to deliver a free-flowing, dynamic sequence drawing allusions to prayer, church and praise dancing in a raised arm, a hand waving, hunched shoulders giving way to uplifted faces. Top-rocking shuffles crisply done pound the sleepy ground awake beneath the dancers’ feet. It’s a churchy revival of 21st-century proportions and sentiments — baptisms beside the point. Purification, cleansing comes from the dance itself, bodies pushing, reaching, flinging, falling, roiling with Harris’s trademark hip hop. Men cartwheel one-armed up from the floor and women tangle up in pretzel shapes, then skitter.

The tension releases. We’ve been waiting for these few powerful, spirit-filled moments the entire evening. We just didn’t know it. While the 16 dancers power through eye-catching mini-solos that feel improvised (but likely aren’t), the audience is encouraged to clap along. In our red velvet seats, we’re momentarily part of the circle — in hip hop terms, the cypher — ready to take a turn with a cool spin or fancy kick. They’re not dancing for us, they’re dancing us.

Harris leads his dancers and onlookers almost to the metaphorical mountaintop, but not quite. A sudden break — it felt like a false ending — gives pause. The stage darkens. The dancers gather close, then one lone man, in silhouette, walks away. Is it Ailey resurrecting? Is it Lazarus? Ailey’s distinctive recorded voice reminisces about what compelled him to create — those “blood memories,” recalling what it was like to grow up black, poor but God-fearing, in small-town Texas.

“Lazarus” does not sugarcoat. Harris’s celebratory sequences feel more real than the easy climax of Ailey’s church-infused “Revelations.” In contrast to the historical images wedded into the collective unconscious of even the most modest student of American history, this homage to Ailey, the man and the creative force, focuses an unforgiving lens on the realities of being black in America today. That was Ailey’s story and his wellspring. Side by side, “Revelations” and “Lazarus” converse about despair and hope, past and future, tradition and innovation. And, of course, the indomitable spirit Alvin Ailey carried, which is now lighting the way to a new generation.

Photos: Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in Rennie Harris’s “Lazarus,” photos by Paul Kolnik, courtesy Kennedy Center.

© 2019 Lisa Traiger

Spice and Spitfire

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Choreography by Alvin Ailey, Kyle Abraham, Robert Battle, Mauro Bigonzetti, Johan Inger, Christopher Wheeldon, Billy Wilson

The Kennedy Center Opera House

Washington, D.C.

February 7 & 8, 2017

By Lisa Traiger

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is looking as strong and beautiful as ever in its annual February visit to The Kennedy Center Opera House. Now in his sixth year as artistic director of the company Alvin Ailey founded in 1958 with the goal of creating a multiethnic modern repertory company, Robert Battle is leaving his imprint. The legendary dancers, including a new younger crop who can tackle both the old school traditional works and contemporary pieces that push them to varying expressive and physical limits, look well honed and perform with amazing strength, flexibility and precision. They can tackle the loose-limbed release technique, balletic pas de deux and conceptual expressionist work. Battle has brought in new repertory including pieces from international choreographers that challenge the dancers and take the company to new realms.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is looking as strong and beautiful as ever in its annual February visit to The Kennedy Center Opera House. Now in his sixth year as artistic director of the company Alvin Ailey founded in 1958 with the goal of creating a multiethnic modern repertory company, Robert Battle is leaving his imprint. The legendary dancers, including a new younger crop who can tackle both the old school traditional works and contemporary pieces that push them to varying expressive and physical limits, look well honed and perform with amazing strength, flexibility and precision. They can tackle the loose-limbed release technique, balletic pas de deux and conceptual expressionist work. Battle has brought in new repertory including pieces from international choreographers that challenge the dancers and take the company to new realms.

Tuesday evening’s opening night program included as much glitz and glamour in the audience as it did on stage. The 18th annual gala for the company brought out a few big names in business and politics and a theater filled with Ailey lovers who collectively raised more than $1 million for the company’s programs. But it was the dancing that shone brightest.

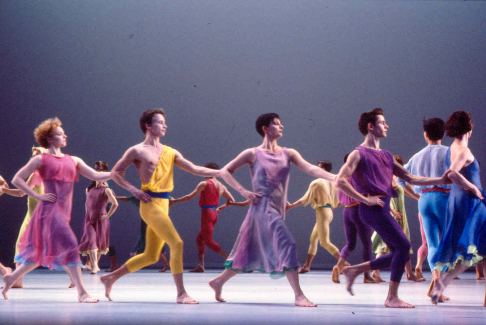

While the company is beloved for Ailey’s works, including the incomparable program closer “Revelations,” it was and remains foremost a repertory company, bringing in works by American and international choreographers. The opener, the late Billy Wilson’s “The Winter in Lisbon,” sparkled in a new production of the choreographer’s 1992 work, here restaged by longtime Ailey associate and assistant artistic director Masazumi Chaya. With Barbara Forbes’ intensely jewel-toned costumes — emerald, amethyst, burgundy and deep orchid dresses, with matching shoes and tights for the women and neat slacks and shirts for the men — the piece showcased the easy going jazz style beloved by Wilson and Ailey. Set to composition by Dizzy Gillespie and jazzman and founder of the D.C. Jazz Festival Charles Fishman, “Winter” was at turns sultry and slinky, snazzy and cool, and all-around lowdown and hot. Dancers slid and rolled through easy going pirouettes, fan kicks, and hip thrusting turns. Men lifted women into soaring split leaps, tucking into smooth spirals on the next beat. Both sexy and fun, it showed off easy virtuosity.

New to the company and to the Kennedy Center, Swedish choreographer Johan Inger’s “Walking Mad” proved both amusing and vaguely inscrutable. Originally created in 2001, but brought into the Ailey rep last year, the piece featured an eight-foot-high wooden wall that became integral to the dance for it could be opened, flattened, pushed into right angles, climbed on, leaned and pushed against and manipulated for varying effects. The dancers clad in nondescript grays and drab dresses on the women, they variously donned trench coats and bowlers or pointy party hats to add a spark of character, color and silliness as Ravel’s “Bolero” built up its stormy froth. Game-like tricks of hide-and seek between opened and closed doorways and one end and the other of this wall provided the light-hearted silliness, and tempered the unfortunate political connotations that talk of a wall brings these days. Inger’s movement vocabulary draws from an improvisational smorgasbord that looks to be influenced by Israeli dance master Ohad Naharin’s Gaga technique. All loose limbs, extreme moments of attack, pedestrian strolls, unsettling tremors and bold highly physical body slams against walls and other dancers make up Inger’s palette. An alum of Nederlands Dans Theater, which includes Naharin’s choreography in its repertory, the similarities are unsurprising.

New to the company and to the Kennedy Center, Swedish choreographer Johan Inger’s “Walking Mad” proved both amusing and vaguely inscrutable. Originally created in 2001, but brought into the Ailey rep last year, the piece featured an eight-foot-high wooden wall that became integral to the dance for it could be opened, flattened, pushed into right angles, climbed on, leaned and pushed against and manipulated for varying effects. The dancers clad in nondescript grays and drab dresses on the women, they variously donned trench coats and bowlers or pointy party hats to add a spark of character, color and silliness as Ravel’s “Bolero” built up its stormy froth. Game-like tricks of hide-and seek between opened and closed doorways and one end and the other of this wall provided the light-hearted silliness, and tempered the unfortunate political connotations that talk of a wall brings these days. Inger’s movement vocabulary draws from an improvisational smorgasbord that looks to be influenced by Israeli dance master Ohad Naharin’s Gaga technique. All loose limbs, extreme moments of attack, pedestrian strolls, unsettling tremors and bold highly physical body slams against walls and other dancers make up Inger’s palette. An alum of Nederlands Dans Theater, which includes Naharin’s choreography in its repertory, the similarities are unsurprising.

Robert Battle’s small, but not inconsequential “Ella,” a tribute and call out to the great jazz singer Ella Fitzgerald, is full of personality, spice and spitfire. A tightly packed duet it takes on Fitzgerald’s incomparable scatting (“Airmail Special”) with verve and impeccable timing by dancers Jacquelin Harris and Megan Jakel. Wednesday night, a second duet, from contemporary ballet choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, showcased the more balletic side of the Ailey aesthetic. The pas de deux from “After the Rain” features an emotional arc as the choreography builds, the dancers, gorgeous Jacqueline Green and Yannick Lebrun, entwining and spiraling, stretching to their utmost and retreating to sensuous moments laying on the floor.

Wednesday evening’s program featured another new to the Kennedy Center work, Italian choreographer Mauro Bigonzetti’s “Deep,” which proved a stunning showcase for the Ailey dancers’ contemporary skills and their multi-lingual dance languages. A dark work, with dancers clad in black on a shadowy stage demarcated by boxes or cubes of light, the choreography fashions the dancers into clumps and pairs executing variations on contorted and broken body positions, emphasizing flexed arms, bent elbows and knees and sharp contrasting torsions of pairs and groups. Contrasting the angularity are curving and undulating or rolling hips and torsos drawing from street moves and hip hop. Hand gestures, too, suggest another cultural construct — perhaps Indian hastas — sign language. The score, club-influenced music by Ibeyi, a pair of twin sisters with French Cuban cultural and musical roots, propels the dancers along showcasing their virtuosity and taut unison. But, “Deep,” with all its cross- or multi-cultural borrowings of movement and music, doesn’t go anywhere. It’s lovely to watch but shallow in its message.

Wednesday evening’s program featured another new to the Kennedy Center work, Italian choreographer Mauro Bigonzetti’s “Deep,” which proved a stunning showcase for the Ailey dancers’ contemporary skills and their multi-lingual dance languages. A dark work, with dancers clad in black on a shadowy stage demarcated by boxes or cubes of light, the choreography fashions the dancers into clumps and pairs executing variations on contorted and broken body positions, emphasizing flexed arms, bent elbows and knees and sharp contrasting torsions of pairs and groups. Contrasting the angularity are curving and undulating or rolling hips and torsos drawing from street moves and hip hop. Hand gestures, too, suggest another cultural construct — perhaps Indian hastas — sign language. The score, club-influenced music by Ibeyi, a pair of twin sisters with French Cuban cultural and musical roots, propels the dancers along showcasing their virtuosity and taut unison. But, “Deep,” with all its cross- or multi-cultural borrowings of movement and music, doesn’t go anywhere. It’s lovely to watch but shallow in its message.

Also new to Washington, Kyle Abraham’s “Untitled America,” a section of his full-evening triptych, left a sobering pall. Drawing on interviews with incarcerated citizens and their family members — which we hear in voiceovers along with a score featuring Laura Mvula, Raime, Carsten Nicolai, Kris Bowers and traditional spirituals, the piece dealt plainly with the current Black Lives Matter movement. Dressed in nondescript gray pants and open tops that from the back could resemble prison jumpsuits, the dancers execute choreographer Abraham’s pain-evoking gestures: hands held aloft in a “don’t shoot” posture, or clasped behind the back as if handcuffed or behind the head for a body search. The half-lit, smoke-filled stage with sharply delineated boxes of light felt oppressive and the dancers, lined up and filed on and off the stage into darkness, like a chain gang. Abraham’s movement is loosely constructed but hard edged, the oppositional attack contrasting the few moments of connection. The work leaves the dancers in their singular isolating bubbles, as voiceovers speak of the loneliness and disconnection of prison life. The hard faces and clenched fists speak powerfully about where Abraham’s America is now.

Also new to Washington, Kyle Abraham’s “Untitled America,” a section of his full-evening triptych, left a sobering pall. Drawing on interviews with incarcerated citizens and their family members — which we hear in voiceovers along with a score featuring Laura Mvula, Raime, Carsten Nicolai, Kris Bowers and traditional spirituals, the piece dealt plainly with the current Black Lives Matter movement. Dressed in nondescript gray pants and open tops that from the back could resemble prison jumpsuits, the dancers execute choreographer Abraham’s pain-evoking gestures: hands held aloft in a “don’t shoot” posture, or clasped behind the back as if handcuffed or behind the head for a body search. The half-lit, smoke-filled stage with sharply delineated boxes of light felt oppressive and the dancers, lined up and filed on and off the stage into darkness, like a chain gang. Abraham’s movement is loosely constructed but hard edged, the oppositional attack contrasting the few moments of connection. The work leaves the dancers in their singular isolating bubbles, as voiceovers speak of the loneliness and disconnection of prison life. The hard faces and clenched fists speak powerfully about where Abraham’s America is now.

That pall lifted as the lights lowered and the hum of a gospel chorus took everyone to Ailey church. His “Revelations,” the 1960 masterwork that closes virtually every program the company dances, has become an expectation for audiences who seek spiritual succor and uplift the indelible choreography. With its traditional gospel score, its journey from slavery to religious renewal to freedom it’s iconic. At the first hummed strains “I Been ‘Buked,” applause takes over. With each emblematic moment — dancers curved over their birdlike arms punctuating the air, the internal struggle made visible through staunch abdominal movements in “I Wanna Be Ready,” the smooth hip rolling walks of “Wade in the Water” — the applause builds. These moments have become iconic, seared into memory by Ailey fans and appreciated for embodied legacy they carry: the choreography itself renders the story of African Americans in vivid wordless moments. At last, a bright, hot sun shimmers on the back scrim and the church-like revival reaches its peak with “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham.” The women wave their straw fans, the men pulse their shoulders and take their loving scolds with equanimity. “Revelations” has become the most-performed, and likely beloved, modern dance in the world. For the company it represents past, present and future, returning young dancers to the root of the company’s ethos and bringing audiences a spiritual charge that will sustain them until next year.

That pall lifted as the lights lowered and the hum of a gospel chorus took everyone to Ailey church. His “Revelations,” the 1960 masterwork that closes virtually every program the company dances, has become an expectation for audiences who seek spiritual succor and uplift the indelible choreography. With its traditional gospel score, its journey from slavery to religious renewal to freedom it’s iconic. At the first hummed strains “I Been ‘Buked,” applause takes over. With each emblematic moment — dancers curved over their birdlike arms punctuating the air, the internal struggle made visible through staunch abdominal movements in “I Wanna Be Ready,” the smooth hip rolling walks of “Wade in the Water” — the applause builds. These moments have become iconic, seared into memory by Ailey fans and appreciated for embodied legacy they carry: the choreography itself renders the story of African Americans in vivid wordless moments. At last, a bright, hot sun shimmers on the back scrim and the church-like revival reaches its peak with “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham.” The women wave their straw fans, the men pulse their shoulders and take their loving scolds with equanimity. “Revelations” has become the most-performed, and likely beloved, modern dance in the world. For the company it represents past, present and future, returning young dancers to the root of the company’s ethos and bringing audiences a spiritual charge that will sustain them until next year.

This season the company included area natives Elisa Clark, who trained at Maryland Youth Ballet; Ghrai Devore; Samantha Figgins who trained at Duke Ellington School of the Arts; Jacqueline Green who danced at Baltimore School for the Arts; Daniel Harder who studied at Suitland High School’s Center for Visual and Performing Arts; and Jermaine Terry.

Alvin Ailey’s “Revelations,” Matthew Rushing and Dwanna Smallwood, photo by Andrew Eccles

Johan Inger’s “Walking Mad,” Jamar Roberts, Jacquelin Harris, and Glenn Allen Sims, photo by Paul Kolnik

Mauro Bignozetti’s “Deep,” choreography Mauro Bignozetti, photo by Paul Kolnik

Kyle Abraham’s “Untitled America,” photo by Paul Kolnik

Alvin Ailey’s “Revelations,” photo by Christopher Duggan

Originally published on DCMetroTheaterArts.com and reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2017 Lisa Traiger

2015: A Look Back

For reasons that continue to surprise me, 2015 was a relatively light dance-going year for me. That said, I managed to take in nearly a top ten of memorable, exceptional or challenging performances over the past 12 months.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, on its annual February Kennedy Center Opera House visit, brought a program of politically relevant works that culminated, as always, in the inspirational paean to the African-American experience, “Revelations.” Up first, though, was the restless “Uprising,” an athletic men’s piece that draws out the animalistic instincts of its performers. Israeli choreographer Hofesh Schechter, drawing influence from his experiences with the famed Batsheva Dance Company and its powerhouse director Ohad Naharin, found the disturbing core in his 40-minute buildup. As these men, in street garb – t-shirts and hoodies – walk ape-like, loose-armed and low to the ground, their athletic sparring, hand-to-hand combat, full-force runs and dives into the floor, ultimately coalesce in a menacing mélange. Is it protest or riot? Hard to tell, but the final king-of-the-hill image — one red-shirt-clad man reaching the apex of a clump of bodies his first raised — could be in solidarity or protest. And, in a season awash in domestic and international unrest, “Uprising,” with its massive large group movement, built into a cri de coeur akin to what happened on streets the world over in 2015.

The Washington Ballet Artistic Director Septime Webre has been delving into American literary classics and on the heels of his successes with both F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, in February his fearless chamber-sized troupe unveiled his latest: a full-length Sleepy Hollow, based, of course, on the ghostly literary legend by Washington Irving. But more than just a haunted night of ballet, Webre’s Sleepy Hollow delved into America’s early Puritan history, with a Reverend Cotton Mather character and a scene featuring witches drawn from elements of the Salem witch trials, expanding the historical and literary context of the work. This new dramatization in ballet, featuring a rich score by Matthew Pierce; well-used video projections by Clint Allen; and scenery by Hugh Landwehr; focuses on the tale of an outsider, Ichabod Crane – a common American literary trope. Choreographically Webre has smartly drawn not only on the expected classical ballet vocabulary, but he also tapped American folk dances and early and mid-20th century modern dance influences to expand the dancers’ roles for greater expressivity and storytelling. Guest principal Xiomara Reyes played the lovely love interest, Katrina Van Tassel, partnered by Jonathan Jordan. It’s hard to say whether this one will become a classic, but Webre’s smartly and carefully drawn characterizations and multi-generational arc in his approach to the Irving’s story expanded the options for contemporary story ballets.

Gallim Dance, a Brooklyn-based contemporary dance company founded by choreographer Andrea Miller, made its D.C. debut at the Lansburgh Theatre in April. Miller danced with Batsheva Ensemble, the junior company of Israel’s most significant dance troupe, and she brings those influences drawn from the unique methodology Naharin created. Called “gaga,” this dance language frees dancers and other movers to tap both their physical pleasure and their highest levels of experimentation. In “Blush,” this pleasure and experimentation played out with Miller’s three women and three men who dive head first into loosely constructed vignettes with elegant vengeance. With a primal sense of attack as they face off on the stage taped out like a boxing ring. Miller’s title “Blush” suggests the physiological change in a person’s body, their skin tone and during the course of “Blush,” transformations occur as the dancers, painted in Kabuki-like white rice powder, begin to reveal their actual skin tones – their blush. In so doing, they become metaphors for shedding a protective outer layer to reveal their inner selves.

The Washington Ballet continued its terrific season with the company’s much ballyhooed production of Swan Lake, at the smaller Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in April. It garnered international attention for Webre’s casting: ballet “It” girl Misty Copeland, partnered by steadfast senior company dancer Brooklyn Mack, became purportedly the first African American duo in a major American ballet company to dance the timeless roles of Odette/Odile and Siegfried, respectively. But that’s not what made this Swan Lake so memorable, and mostly satisfying. Instead, credit goes to former American Ballet Theatre principal Kirk Peterson, responsible for the indelible staging and choreography, following after, of course, Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. He drew exceptional performances from this typically less than classical chamber-sized troupe. The corps de ballet, supplemented by senior students and apprentices, really danced like a classical company. As well, Peterson, who has become an expert in resuscitating classics, returned little-seen mime passages to the stage, bringing back the inherent drama in this apex of story ballets. My favorite is the hardly seen (at least in the U.S.) passage when Odette, on meeting Siegfried in the forest in act II, tells him the story of her mother, evil Von Rothbart’s curse and the lake, filled with her mother’s tears, as she gestures in a horizontal sweep to the watery backdrop and brings her forefingers to her eyes indicating dropping tears. Live music was provided by the Evermay Chamber Orchestra and made all the difference for the dancers, even though the company’s small size meant the act III international character variations were cut. While the hype focused on the Copeland debut, she didn’t own or carry the ballet, and here Mack was a solid, but not entirely warm Siegfried. This Swan Lake truly soared truly through the corps, supporting roles and staging.

June brought the Polish National Ballet, directed by Krzysztof Pastor, to the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in lovely evening of contemporary European works. The small company – 11 women and a dozen men – are luscious and intelligent dancers who can captivate in works that push beyond staid classical technique. Pastor’s program opener, “Adagio & Scherzo,” featuring Schubert’s lyricism, twists, winds, and unfurls in pretty moments. There is darkness and light, both in the choreography and in designer Maciej Igielski’s illumination, which matches the shifting moodiness of the score. Pastor’s movement language is elegant, but not constrained, his dancers breathe and stretch, draw together and nuzzle in more ruminative moments, then split apart. In his closer “Moving Rooms” we first meet the dancers arranged in a checkerboard pattern on a black stage, each dancer contained in an single box of light. Using the sometimes nervously itchy score by Alfred Schnittke and Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki, the dancers, clad in flesh colored leotards, used their legs and arms in sharp-edged angles and geometries. But the centerpiece of the evening was a new “Rite of Spring” – yes, to that Mt. Everest of scores by Igor Stravinsky – this one is choreographed by French-Israeli Emanuel Gat. Danced on a red carpet, the five dancers ease into a counterintuitive tango of changing partners, always leaving one dancer as the odd one out. The smooth and slightly sensuous salsa is the basis for the work’s movement sinuous vocabulary, as it quietly builds like a slowly simmering pot put to boil.

Man and machine – or in this case – dancer and computerized robot – meet in Taiwanese-born choreographer and dancer Huang Yi’s 50-minute work. The evening presented in The Clarice’s Kogod Theater, its black box at the University of Maryland in September, provided a merging of art and technology. KUKA, the German-made robot, used in factories around the world to insert parts that build autos and iPads, has become a companion and artistic partner for Yi. Performing to a lushly classical score of selections from Bach and Mozart, Yi, clad in a dark suit, dances with, beside and around the singular movable robot arm sprouting from KUKA’s bright orange base. There are moments of serendipity, when the two seem to be communing in a duet of machine and motion, and others, in the dimly lit work, when each strays off on a tangent – robot and human, may move side by side, or even together, but only one inhabits a spiritual profound space of flesh, blood and breathe. That was my take away from this intriguing experiment in technology and dance. Yi is at the forefront of merging art with new technology and his experimentation – he programmed the robot – is on the cutting edge, but the work doesn’t cut to the quick. Still, orange steel and computer chips don’t trump muscle, bone, flesh and spirit. I would like to see more of Yi’s slippery, easy silken movement, in better light and with living breathing partners.

Man and machine – or in this case – dancer and computerized robot – meet in Taiwanese-born choreographer and dancer Huang Yi’s 50-minute work. The evening presented in The Clarice’s Kogod Theater, its black box at the University of Maryland in September, provided a merging of art and technology. KUKA, the German-made robot, used in factories around the world to insert parts that build autos and iPads, has become a companion and artistic partner for Yi. Performing to a lushly classical score of selections from Bach and Mozart, Yi, clad in a dark suit, dances with, beside and around the singular movable robot arm sprouting from KUKA’s bright orange base. There are moments of serendipity, when the two seem to be communing in a duet of machine and motion, and others, in the dimly lit work, when each strays off on a tangent – robot and human, may move side by side, or even together, but only one inhabits a spiritual profound space of flesh, blood and breathe. That was my take away from this intriguing experiment in technology and dance. Yi is at the forefront of merging art with new technology and his experimentation – he programmed the robot – is on the cutting edge, but the work doesn’t cut to the quick. Still, orange steel and computer chips don’t trump muscle, bone, flesh and spirit. I would like to see more of Yi’s slippery, easy silken movement, in better light and with living breathing partners.

Camille Brown went deep in mining her childhood experiences in Black Girl: Linguistic Play, presented by The Clarice in the Ina & Jack Kay Theatre in October. The evening-length work draws on Brown’s and her dancers’ playground experiences, first as young girls playing hopscotch, double dutch jump rope and sing-songy hand clapping games. On a set of platforms, chalk boards that the dancers color on and hanging angled mirrors designed by Elizabeth Nelson, Brown and her five women dancers inhabit their younger selves, in knee socks, overall shorts, and all the gum-chewing gumption and fearlessness that seven-, eight- and nine-year-olds own when they’re comfortable in their skin. As the piece, featuring a live score of original compositions and curated songs played by pianist Scott Patterson and bassist Tracy Wormworth hit all the right notes as the performers matured and grew before our eyes from nursery rhyming girls chanting “Miss Mary Mack” to hesitant pre-adolescents, fidgeting and fighting mean-girl battles, to teens on the cusp of womanhood – and uncertainty. The work is a vibrant and vivid rendering of the secret lives of the little seen and less heard experiences of black girls. The movement is pure play: physical, elemental, skips and hops, the stuff of recess and lazy summer days. But there are moments of deep recognition, particularly one where an older sister or mother figure gently, carefully, lovingly plaits the hair of one of the girls. Its quiet intimacy, too, speaks volumes.

The dance event of the year was likely the much heralded 50th anniversary tour celebrating Twyla Tharp’s choreographic longevity and creativity. For the occasion at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater in November, she pulled together a 13-member ensemble of some of her long-time dancers and some younger favorites – multi-talented performers who can finesse a quick footed petit allegro or execute a jazzy kick-ball-change and slide sequence or bop and rock in bits of freestyle improvisation with equal skill. For the two Tharp did not revive earlier masterpieces, instead she paid a sort of homage to her elf with a pair of new works – “Preludes and Fugues” and “Yowzie.” Each had elements of hat smart synchronicity that Tharp favors, her beloved little balletic passages that she came to embrace after years of more severe post modernism, and her larky, goofy wiggles, scrunches, and witty physical jokes, like pairing the “tall” girl with the shortest guy in the company, or little games of tag or chase and odd-one-out that are interspersed in both works. “Preludes and Fugues” was preceded by “First Fanfare,” featuring a herald of trumpets composed by John Zorn (and performed by the Practical Trumpet society). The two works, one a bit of appetizer, the other the first course, bled into each other and recalled influences of Tharp’s earlier beloved choreography, especially the indelible ballroom sequences and catches of “Sinatra Suite.” “Preludes and Fugues” is as staunch piece set to Bach fugues that Tharp dissects choreographically with precise footwork, intermingling couples, groups and soloists and her eye for the “everything counts” ethos of post-modernism where ballet and jazz, loose-limbed modern and a circle of folk like chains all blend into a whole.

“Yowzie” is brighter, more carefree, recalling the unbridled energy of a New Orleans Second Line with its score of American jazz performed and arranged by Henry Butler, Steven Bernstein and The Hot 9. Dressed in mismatched psychedelia by designer Santo Loquasto the dancers grin and mug through this more lighthearted romp featuring lots of Twyla-esque loose limbs, shrugs, chugs and galumphs along with Tharpian incongruities: twos playing off of threes, boy-girl couplings that switch over to boy-boy pairs, and other hijinks of that sort. The dancers have fun with the work, its floppiness not belying the technical underpinnings that make the highly calibrated lifts, supports, pulls and such possible. The carnivalesque atmosphere feels partly like old-style vaudeville, partly like Mardi Gras. In the end though, both works are Twyla playing and paying homage to Twyla – they’re both solid, smart and well-crafted. They’re not keepers, though, in the way “In the Upper Room,” “Sinatra Suite,” or “Push Comes to Shove” were earlier in her career.

Samita Sinha’s bewilderment and other queer lions is not exactly dance or theater, but there’s plenty of movement and mystery and beauty in her hour-long work, which American Dance Institute in Rockville presented in early December. In a year of no Nutcrackers for this dance watcher, this was a terrific antidote to the crushing commercialization of all things seasonal during winter holidays. Sinha, a composer and vocal artist, draws on her roots in North Indian classical music as well as other folk, ritual and classical music traditions. Together with lighting, electronic scoring, a collection of props and objets (visual design is by Dani Leventhal), she has woven together a world inhabited by creative forces and energies from across genres and encompassing the four corners of the aural world. Ain Gordon directed the piece, which sometimes featured text, sometimes just vocalizing, sometimes movement as Sinha and her compatriots on stage Sunny Jain and Grey Mcmurray trade places, come together to play on or work with a prop, like a fake fur vest or scattered collected chairs and percussive instruments. There were eerie keenings, and deep rumbles, higher pitched vocalizations, cries, exhales, sighs, electric guitar and steel objects banged together, all in the purpose of building a world of pure and unclichéd vocal resonance. It would be too easy to compare her to Meredith Monk and Sinha is far less artistically self-conscious and precious. She is most definitely an artist to follow. Her vision and talent, keen eye and gracious presence speak – and sing – volumes.

© 2015 Lisa Traiger

Published December 31, 2015

A Personal Best: Dance Watching in 2012

Like many, my 2012 dance year began with an ending: Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Much was written on the closure of this 20th-century American treasure after more than 50 years, especially its final performance events on the days leading up to New Year’s Eve 2012. At the penultimate performance on December 30, the dancers shone, carving swaths of movement from thin air in the hazy pools of light spilling onto raised platform stages in the cavernous Park Avenue Armory space. A piercing trumpet call emanated from the rafters heralding the start of this one-of-a-kind evening. Pillowy, cloud-like installations floated above in near darkness. Throughout, snippets of Cunningham choreography – I saw “Crises,” “Doubles” and maybe “Points in Space” – came and went, moving images played for the last time, while audience members sat on folding chairs, observed from risers or meandered through the space, taking care not to step on the carpeted runways that the dancers used to travel from stage to stage.

I found it refreshing to get so close to the dancers after years of partaking of the Cunningham company in theatrical spaces, for me most commonly the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. Here the dancers became human, sweat beads forming on their backs, breathe elevated, hair matting down toward the end of the evening. Duets, trios, groups formed and dissolved in that coolly unemotive Cunningham fashion, with alacrity they would step off the stage and rest and reset themselves before coming back on again for another round of the complex alphabet of Cunningham bends, pelvic tilts, lunges, passes, springs, jumps and playful leaps. While the dancers energy surged, I felt time was growing short. The end near. I soon found myself on a riser standing directly above and behind music director Takehisa Kosugi who at the keyboard conducted the ensemble and held an digital stop watch. Journalists traditionally end their articles with – 30 –. Here, momentarily I got distracted with the numbers: 41’38”, 41’39”, 41’40”, 41’41” … And then within a minute Kosugi nodded and squeezed his thumb: at 42’40”. An ending stark, poignant, and by the book.

In January, the Mariinsky Ballet’s “Les Saisons Russes” program was an eye opener on many levels. The work of Ballets Russes that stunned Paris then the world from 1909 through 1914 under the astute and market-savvy vision of Serge Diaghilev, remains incomparable for audiences today. The triple bill of Mikel Fokine works wows with its saturated colors and vividly wrought choreographic statements, impeccably executed by Mariinsky’s stable of well-trained dancers. These three ballets – “Chopiniana” from 1908, and “The Firebird” and “Scheherazade” from 1910 – continue to pack a powerful punch, a century after their creation. The subtle Romanticism distilled with elan by the Mariinsky corps de ballet — from the perfection etched into their curved arms and slightly tilted heads, their epaulment unparalleled — makes one pine for a bygone Romantic era that likely never actually attained this level of technical grace and precision. With “Firebird,” the Russian folktale elaborately retold in dance, drama and vibrantly outlandish costumes, the flamboyant folk characters were part ‘80s rock stars, part science fiction film creatures. Finally, the bombast and melodrama of the Arabian Nights rendered through Fokine’s version of “Schererazade” danced as if on steroids provided outsized exoticism, with more sequined costumes, scimtars and false facial hair and the soap operatic performances to suit the pompous grandeur of the Rimsky-Korsakov score. Surely Diaghilev would have approved.

Also in January, Mark Morris Dance Group returned to the Kennedy Center Opera House with its brilliant L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato, danced with humanity and glee to Handel’s oratorio, itself based on 17th-century pastoral poem by John Milton and the watercolor illustrations of William Blake. Morris – and Milton, Blake and Handel – each strove for a utopian ideal. This work draws together its disparate parts into one of the great dance works of the 20th century. Enough has been spoken and written about this glorious rendering in music, with the full-voiced Washington Bach Consort Chorus, wildly overblown and softly understated dancing from an expanded company of 24 elegant and spirited movers, and set design – vivid washes of color and light in ranging from flourish of springtime hues to fading fall colors — by Adrianne Lobel. L’Allegro was produced abroad, in 1988 when Morris and his company were in residence at the Theatre Royale de la Monnaie in Belgium, at a time and a place when dance received unprecedented financial and artistic support. I was struck by the open democratic feeling of the dancers, each on equal footing, soloists melding into groups, humorous bits shifting to serious interludes, no dancer stands out individually. For Morris, whose roots date back to folk dance, the community, the group, the natural feeling of people dancing together is valued above the singularity of solo dancing. It’s democracy – small d – at its best. Watching the work again this year, as dance companies large and small balance at the edge of a seemingly perpetual fiscal cliff, was a reminder of how small and cloistered American modern dance has become. We have few choreographers with the resources and the daring to attempt the bold and brash statements that Morris harnessed in L’Allegro.

Another company that leaves everything on stage but in an entirely different vein is Tel Aviv’s Batsheva Dance Company, which I caught at Brooklyn Academy of Music in March. Hora, an evening-length study in gamesmanship and internalized worlds made visible was created by company artistic director (and current world-renowned dance icon) Ohad Naharin. With his facetiously named Gaga movement language, dancers attained heightened sensitivity, not dissimilar to the work butoh masters and post-modernist strove for in earlier decades. And yet the steely technical accomplishment and steadfast allegiances to dancing in the moment that Gaga pulls from its best proponents makes Batsheva among the world’s most prized and praised contemporary dance companies. At BAM, the 60 minute work with its saturated colors and pools of shifting lighting by Avi Yona Bueno and music arranged by Isao Tomita featuring snippets from Wagner, Strauss, Debussy and Mussorgsky offers a smorgasbord of familiarity as the dancers parse oddly shaped lunges with hips askew, pelvises tucked under, ribs thrust forward and heads cocked just so. Odd and awkward, yet athletic and graceful, and undeniably daring Naharin mines his Batsheva dancers for quirks that become accepted as fresh 21st century bodily configurations. Though named Hora, the work has nothing whatsoever to do with the ubiquitous Jewish circle dance, yet after an evening with Batsheva, it’s hard not to feel like celebrating.

Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz in “Necessary Weather,” with lighting by Jennifer Tipton, photo: Stephanie Berger

In April, Sara Rudner and Dana Reitz glimmered in “Necessary Weather,” a subtle tour de force filled with small moments of great and profound drama and even, unexpectedly, a smile or two. The glide of a foot, cock of a head, even a raised eyebrow or tip of a hat from Rudner and Reitz resonated beneath the glow of Jennifer Tipton’s lighting, which in American Dance Institute’s Rockville studio theater, performed a choreography of its own glowing, fading, saturating and shimmering.

Also at ADI in May, Tzveta Kassabova created a rarified world – of the daily-ness of life and the outdoors. By bringing nature inside and onto the stage, which was strewn with leaves, decorated with lawn furniture, and, in a coup de theatre, a mud puddle and a rain storm. Her evening-length and richly rendered Left of Green, Fall, choreographed on a wide-ranging cast of 16 child and adult dancers and movers, featured sound design and original music with a folk-ish tinge by Steve Wanna. The work tugs at the outer corners of thought with its intermingling of hyper-real and imagined worlds. The senses also come into play: the smell of drying leaves, the crackly crunch they make beneath one’s feet and the moist-wet smell of fall is startling, particularly occurring indoors on a sunny May afternoon. Kassabova, with her flounce of bouncy curls and angular, sharp-cornered body, dances with a laser-like intensity. She’s ready to play, allowing the sounds and sights of children in a park, sometimes among themselves, other times with adults. She’s also game to show off awkwardness: turned in feet, sharp corners of elbows, hunched shoulders and flat-footed balances – providing refreshing lessons that beauty is indeed present in the most ordinary and the most natural ways the body moves.

The Paris Opera Ballet’s July stop at the Kennedy Center Opera House brought an impeccable rendering of one of the pinnacles of Romantic ballet: Giselle. And should one expect anything less than perfection when the program credits list the number of performances of this ballet by the company? On July 5, 2012, I saw the “760th performance by the Paris Opera Ballet and the 206th performance of this production,” one with choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot dating from 1841, transmitted by Marius Petipa in 1887 and adapted by Patrice Bart and Eugene Polyakov in 1991. Two days later it was 763. The POB still uses the 1924 set and costume designs of the great Alexandre Benois, adding further authenticity to the work. But nothing about this production is museum material. POB continues to breathe life into its Giselle.

Aside from making a pilgrimage to the imaginary graveside of the tragic maiden dancer two-timed by her admirer, it’s hard to find a more accurate and handsome production of this ballet masterpiece. Aurelie Dupont was a thoughtful and sophisticated Giselle, care and technical virtuosity evident in her performance, while her Albrecht, Mathieu Ganio, played his Romantic hero for grandeur. While the 40-something husband and wife duo of Nicholas Le Riche and Clairemarie Osta on paper make an unlikely Albrecht and Giselle, in reality their heartfelt performances were so intensely and genuinely realized at the Saturday matinee that they felt as youthful as Giselles and Albrechts a generation younger.

The production is as close to perfection on so many levels that one might ever find in a ballet, starting with a corps de ballet that danced singularly, breathing as one unit, most particularly in the act II graveside scene. The mime passages, too, were truly beautiful, works of expressive artistry many that in most companies, particularly the American ones, are dropped or given short shrift. Here the tradition remains that mime is integral to the choreography, not an afterthought but a moment of import. Most interesting was a (new to me) mime sequence by Giselle’s mother about the origins of her daughter’s affliction and how she will most definitely die (hands in fists, crossed at the wrists, held low at the chest). Later when the Wilis dance in act II, it becomes abundantly clear why their arms are crossed, though delicately, their hands relaxed: they’re the walking dead, zombies, if you will, of another era. Another unforgettable moment in POBs Giselle, is its use of tableaux at then ending moment of each act. Each act ends in a moment of frozen stillness – act one of course with Giselle’s death, act two with the resurrection of Albrecht. Each of these is captured in a stage picture, then the curtain dropped and rose again – and there the dancers stood, still posed in character. Stunning and memorable.

Each year in August the Karmiel Dance Festival swallows up the small northern Israeli city of Karmiel as upwards of reportedly 250,000 folk and professional dancers swarm the city for three days and nights of dance. From large-scale performances in an outdoor amphitheater to professional and semi-professional and student companies performing in the municipal auditorium and in local gymnasiums and schools to folk dance sessions on the city’s six tennis courts, Karmiel is awash in dance. I caught companies ranging from the silky beauty of Guangdong Modern Dance Company from China’s Guangzhou province, France’s Ballet de Opera Metz under the direction of Patrick Salliot, the youthful and vivacious CIA Brasileira De Ballet, where artistic director Jorge Texeira seeks out his youthful dance protégés from the streets and barrios of some of the poorest neighborhoods in Rio de Janeiro, Terrence Orr’s Pittsburgh Ballet Theater, and Israel’s Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company, directed by Rami Be’er in a program of new works by young dancemakers. Maybe not the best that I saw, but the unforgettable oddity of the three-day festival was the headlining company, billed as the Cossack National Dance Troupe from Russia. In the grand folk dance tradition of the great Moiseyev company of Russia, these dancers, musicians and singers – numbering 60 strong – let the sparks fly, literally. With breathtaking sword play where white hot sparks truly did fly from the swords, to astounding acrobatic feats and graceful, feminine dances featuring smoothness, precision and delicate footwork parsed out in heeled character boots, the troupe was a hit. Few in the appreciative Israeli crowd – many of whom sang along to the old Russian folk songs buying into a mythic pastoral vision of the Cossack warriors – seemed aware of the irony of an audience of predominantly Israeli Jews heartily applauding a show titled “The Cossacks Are Coming!” The last time Jews were heard to say “The Cossacks are coming,” things didn’t turn out so well.

In September, Dance Place was fortunate to book one of the State Department’s CenterStage touring troupes at the top of its season. Nan Jombang, a one-of-a-kind family of dancers from the Indonesian island of Sumatra, provided a remarkable and moving evening in its North American premiere. Rantau Berbisik or “Whisperings of Exile” begins with a siren call, a female shriek that’s an alarm and cry of pain, that begins a journey of unexpected images. Ery Mefri, a dancer from Padang, on the western coast of Sumatra, has created a surprisingly original dance culture drawing from traditional tribal rituals, martial arts – randai and pencak silak – captivating chants and unusual body percussion techniques. But most unique about Mefri’s artistic project, and the company he founded in 1983, is that it is truly a family affair: the five dancers are his wife and children. The live, sleep, eat and work together daily in intense isolation crafting dances of elemental power and uncommon dynamism through an intensely intimate process.

The work features a trio of gloriously powerful women who exhibit strength of body and will in the earthbound manner they dive into movement, oozing into deep plie like squats and then pounding the taut canvas of their stretched red pants like drummers. Moments later they spring forth from deep lunges, pouncing then retreating, only to strike out again. The hour-long work is filled with mystery and mundanity: dancers carry plates and cups back and forth from a tea cart, rattling the china in percussive polyrhythms, and one woman sits in a chair and keens, rocking and hugging herself for an inconsolable loss. Later the women pass and stack plates around a wooden table with an urgency and assembly-line precision that brings new meaning to the term woman’s work. The one thin boy/man in the group attacks and retreats with preternatural grace, sometimes part of this female-dominated social structure, other times apart – an outcast or loner. And throughout amid the bustle, the urgent calls, the unmitigated pain and sense of loss, there remains a stunning impression of yearning, of hope. The ancient rituals of home and hearth, of work and rest, of group and individual it seems are drawn from a language and way of life that Mefri sees disappearing. Quickly evident in this riveting evening is how Mefri and his family can communicate so deeply to the heart and soul in ways that strike at the core, of unspoken truths about family, community and cultural continuity and conveyance.

One final note of continuity and cultural conveyance was struck resoundingly in December with Chicago Human Rhythm Project’s “Juba: Masters of Tap and Percussive Dance” at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater. While the program was long on youth and short on masters – an indication that we’ve reached the end our last generation of true tap masters — Dianne “Lady Di” Walker represented the early tap revival providing the link to old time rhythm tap of the early and mid-20th century. The program, emceed and curated by Lane Alexander of CHRP, brought together a bevy of youthful dance companies, among them Michelle Dorrance’s Dorrance Dance with an interesting excerpt for two barefoot modern dancers and a tapper. D.C. favorite Step Afrika! brought down the first act curtain with its heart-raising rhythms and body slapping percussion. And, closing out the evening, Walker served up “Softly As the Morning Sunrise,” a number as smooth and bubbly as glass of Cristal, her footwork as fast as hummingbird wings, her physics-defying feet emitting more sounds than the eye could see. This full evening of tap also included Derik Grant, Sam Weber, and younger pros Jason Janas, Chris Broughton, Connor Kelley, Jumaane Taylor, Joseph Monroe Webb and Kyle Wildner. The evening with its teen and college aged dancers sounded a note that tap will continue to be a force to reckon with in the 21st century. That it occurred on a main stage at the Kennedy Center was – still – a rarity. Let’s hope the success of this evening will lead to more forays into vernacular and percussive dance forms at the nation’s performing arts center. The clusters of tap fans young and old gathered in the lobby after the show couldn’t bear to leave. If they had thrown down a wooden tap floor on the red carpeting, no doubt folks would have stayed for another hour of tap challenges right there in the lobby.

***

And I can’t forget a final, very personal experience. During the annual Kennedy Center run of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in February, I found myself pulled from my aisle seat to join the dancers onstage in Ohad Naharin’s “Minus 16,” which the company had just added to its repertory in late 2011. Clad in slim fitting business suits and stark white shirts, the dancers make their way to the lip of the stage and stare. The next thing you know, they’re stalking the aisles, climbing over seats, crawling across laps to bring up randomly selected members of the audience. The sequence is fascinating – a mix of the mundane, the ridiculous and the dancerly – inviting in the human element as these god-like dancers canoodle, slow dance, cha-cha and indulge their new-found partners. Soon they corral the group, circle, and in ones and twos the dancers begin to lead the participants off stage, leaving just one – most frequently a woman – standing in the embrace of her partner as the others hug themselves in a smug slow dance. On cue the dancers fall. The woman remains alone, in the spotlight. Frequently aghast, embarrassed, she slinks away.

Dreamlike is the best way I can describe the experience. Audience members seem to be selected according to a particular color, most frequently red judging from the previous times I’ve seen the work. As a “winter” on the color chart, I, of course, frequently wear red from my beret to my purse to a closet full of sweaters and blouses. When the dancers lined up, I felt one made eye contact with me right away. I didn’t avert my gaze and I thought that I could be chosen. But as they came into the audience, he passed me by and I exhaled slightly, relieved not to be selected. The stage re-filled with dancers and their unwitting partners as I watched. Suddenly, the same dancer who caught my eye was at my side beckoning, pulling me from my seat. My hand in his I followed him down the dark aisle and up the stairs. There the music changed frequently from kitschy ‘60s pop to rumba, cha cha, and tango – all recognizably familiar, a Naharin trait. Yet the choreographer definitely wants to keep the novices off guard, which is disconcerting because there are moments when the dancers are completely with you and you feel comfortably in their care, then they leave you to your own devices and all bets are off.

I realized quickly that I had to focus fully on my partner and not get distracted by what others on stage or in the audience were doing. We maintained eye contact throughout and went through a bevy of pop-ish dances: I recall bouncing, lunging, throwing in a bump or two and a great tango – wow, what a lead. Then they mixed things up, pushing all the civilians into a circle then a clump before reshuffling things. Somehow I came out with a new partner and things really heated up as I followed him and he me. I felt my old contact skills tingling back to life as I tried to give as good as he gave. He dipped me and I suspect that when he felt I gave in to it, he realized he could take me further. I don’t know how, but I found myself lifted above his head in what felt like a press. As he turned, I thought I might as well take advantage of this. I’m never going to be in the arms of an Ailey dancer again. I put one leg in passe, straightened the other, threw my head back and lifted my sternum, while keeping one hand on my head so my beret wouldn’t fly. He likely only made two or three rotations, but in my mind it felt like a carnival carousel: incredible. Back on earth with my feet on solid footing, he tangoed and embraced me. I knew what was coming. The slow dance when they lead partners off stage. I realized I might was well give in to the moment, I melted into his embrace and we swayed. Two bodies as one. Eyes closed. I momentarily opened them when I sensed the stage emptying. The only words spoken between us are when I said, “uh oh.” He squeezed me and then dropped to the floor in an X with the remaining Ailey dancers. There I was. Alone. Center stage in the Kennedy Center Opera House. I have been seeing performances there since I was a child in 1970s. I had seconds to decide what I was going to do. “%^&#) it,” I said to myself. “I’m standing here in the Opera House with 2,500 people looking at me. I’m going to take my bow.” I moved my leg into B+, opened my arms with a flourish, dropped my head and shoulders and rose, relishing the moment for all it was worth. Seconds later, the audience roared. I was stunned. I made my way gingerly off stage, still blinded by the spotlights as I fumbled up the aisle to find my seat.

Dreamlike. Throughout I knew this was something I would want to relish and remember and tried to find markers for while maintaining the presence of the moment. I was able to find out who the dancers were (yes, there were two) who partnered me. But I believe that Naharin wants the mystery to remain both for the onlookers and the participants. At intermission people were asking if I was a “plant,” insisting that I must have known what to do in advance. But, no, Naharin wants that indeterminacy, that edginess, that moment of frisson, when the audience realizes that with folks just like them on stage, all bets are off on what could happen. While we often attend dance performances to see heightened, better, more beautiful and more physically fit and skilled versions of ourselves (one of the reasons, I think, that we also watch football, basketball and the like), there’s something about seeing someone just like you or me up on stage. If the middle aged mom who needs to get the kids off to school then go to work the next morning can have such a rarified experience then maybe, just maybe, the rest of us can rediscover something fresh, untried, daring, out of sorts, amid the banality of our everyday lives. In this brief segment – and I couldn’t tell you how long it lasted, but I’m sure not more than five minutes at most – Naharin, through the heightened skill and beauty of professional dancers, offers escape from the ordinary. Audiences live through it vicariously by seeing one of their own up there on stage. For me the experience was unforgetable.

© 2012 Lisa Traiger

Published December 30, 2012

leave a comment