New Season: New Hope?

District Choreographer’s Dance Festival

Dance Place, presented at Edgewood Arts Center, Brookland Arts Space Lofts Studio, Dance Place Arts Park, Dance Place roof, offices, and Cafritz Foundation Theater

Choreography: Kyoko Fujimoto, Dache Green, Claire Alrich, Shannon Quinn of ReVision Dance Company, Gerson Lanza, Malik Burnett, and Colette Krogol, and Matt Reeves of Orange Grove Dance.

Washington, D.C.

September 9 – 10, 2023

When Dance Place opened its season each September, it heralded a surfeit of dance performances for the next 11 months. In fact, the nationally known presenter for decades offered up live dance performances across genres from modern to African forms, tap, bharata natyam (a classical Indian form), hip hop, flamenco, performance art, post-modern, raks sharki (belly dance), salsa rueda, stepping, even contemporary ballet, to mention just a few. Dance lovers could be assured of a show nearly every weekend of the year from September through June, with a smattering of performance options spread across the summer. Most years during its heyday, Dance Place presented between 35 and 45 weeks of dance annually, from both regional companies and national and international artists. Among those were first D.C. performances (pre–Kennedy Center invitations) from David Parsons Dance, Urban Bush Women, Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, Rennie Harris/Puremovement, Blue Man Group, and dozens of others. And along with well-curated programming, the organization offered professional and recreational studio classes in modern dance, West African dance and other forms, and a free summer arts camp for neighborhood children.

The feat, presenting more dance annually than the Kennedy Center, happened under the indefatigable visionary leadership of founding director Carla Perlo and her co-director Deborah Riley. Since they stepped away from leadership in 2017, the nationally renowned organization has struggled to find its new identity under two different artistic directors, an acting director, a global pandemic, and presently little institutional knowledge regarding the organization’s outsized influence in the dance world.

But season openings always offer a fresh opportunity to hope.

The 2023/24 season marks Dance Place’s 44th year. September 9 and 10, the organization chose to continue a tradition of showcasing locally based artists in new and recent works, which dates back to the Perlo and Riley era, and “post-pandemic” Christopher K. Morgan named the season opener the District Choreographer’s Dance Festival. This year, Dance Place and seven choreographic artists showcased not only their works but also the studio, performance, and space assets the organization manages and has access to along 8th Street NE, hard by the Metro and railroad tracks, just a short walk from Catholic University.

The afternoon began at Edgewood Arts Center, a community room used for weddings, parties, classes, and the like. Choreographer Kyoko Fujimoto, who also holds a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, fashioned a contemporary ballet quartet featuring point work and lifts, punctuated by the angularity of 90-degree elbows and knees — perhaps an ever-so-slight nod to Balanchine’s mid-20th-century neo-classicism. The work, “into the fields,” was meant to recall the experience of a medical MRI. That was evident in the horizontal crossings of single dancers rising and falling like pointed peaks and valleys of a heart monitor readout. It could also be heard in Caroline Shaw’s music from “Plan & Elevation” and another musical sequence from V. Andrew Stenger and Fujimoto. The stark black biker shorts and white tops provided an ascetic look for dancers Sara Bradna, Ian Edwards, Max Maisey, and Sophia Sheahan.

The audience was then led down the street to a Brookland Arts Space Loft studio for performer/choreographer Dache Green’s “Evolution(ary).” In the tight, bare studio, Green, long, lean and powerful, struts forward in chunky black heels, jean shorts, and an olive green trench coat. Viola Davis’ resonant voice is heard in her famous 2018 speech for Glamour magazine: “I’m not perfect. Sometimes I don’t feel pretty. Sometimes I don’t want to slay dragons … the dragon I’m slaying is myself …” To that, and then to a Beyonce-heavy score — “I’m That Girl,” “Church Girl,” “Thick,” “All Up in Your Mind,” peppered with other artists like Kentheman, Inayah Lamis, and Annie Lennox and the Eurhythmics — Green grabs center stage like a model on a catwalk, owning the space and moment as he poses, struts, bumps and grinds, vogues and twerks, all the while lip-syncing. It’s a public and private confessional about discovering and owning one’s personal story with power and self-love, acceptance, and being fierce.

Back outside in the partly cloudy afternoon, if one didn’t look up, you’d miss ReVision Dance Company’s Amber Lucia Chabus and Chloe Conway, clad neck to ankle to fingertips in highlighter pink and highlighter green respectively, poking a jazz hand, leg, or foot out from the Dance Place Roof. Choreographer Shannon Quinn let her two dancers loose on the roof to play with each other and with the viewers two stories below. I recalled film and photos of choreographer Trisha Brown’s 1971 “Roof Piece” and loved this nameless piece d’occasion all the more for its nod to post-modern dance history, while not taking itself too seriously, including playful moments and silly mime as the duo stepped down to disappear, then pop up seconds later in another location.

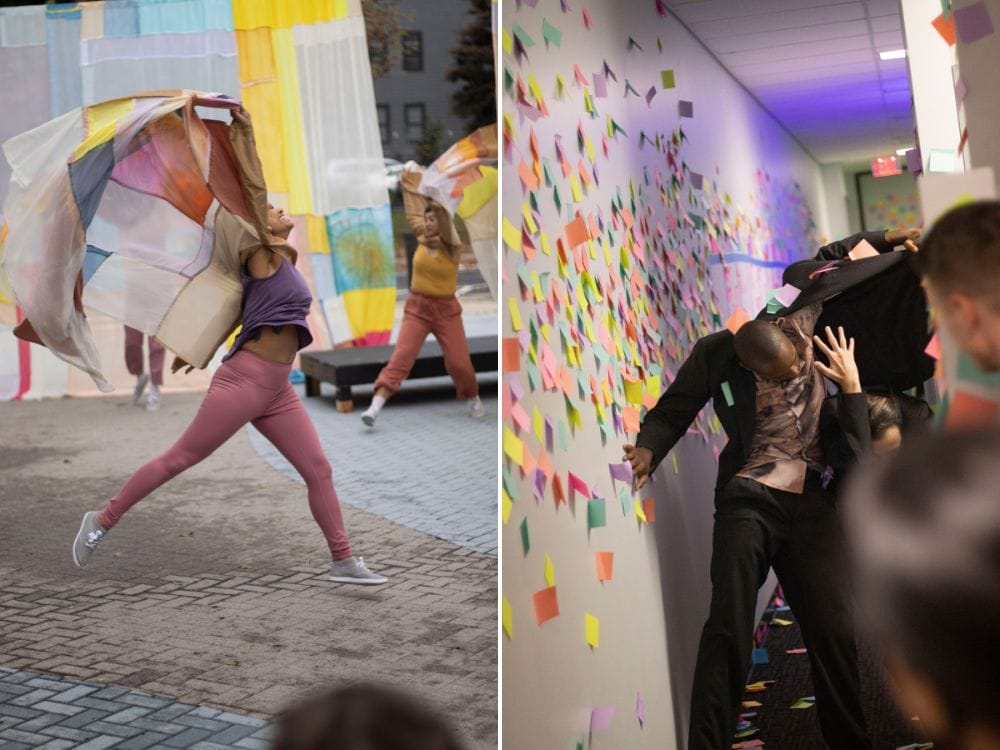

Claire Alrich’s “scenes from an elevator ascending” spread out on the Arts Park, a former city easement of land Perlo developed into a multi-use space for the community to congregate between Brookland Arts Lofts and Dance Place. With a set of stitched-together curtain-like panels and flowing cape-like tunics in mauve, mustard, and cantaloupe colors designed by Alrich and Mara Menahan, the three dancers stretch their arms to work the expanse of the costume. The work feels like an organic transformation in process. I was reminded of the caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly cycle, particularly as the dancers gently left the space walking away down Kearny Street as Santiago Quintana’s score faded.

“Paper Jungle” was meant to be a ten-minute experiential piece for ten people at a time to walk through the upstairs office cubicles of Dance Place. Technical delays kept groups waiting, but Orange Grove Dance, helmed by choreographic and design partners Colette Krogol and Matt Reeves, is consistently worth a wait. Entering the tightly constricted hallway, walls scattered with Post-it notes, “Paper Jungle” featured dancers Robert Rubama and London Brison joined by Reeves, who at times carried an open laptop on record. Audiences waiting in the downstairs lobby could watch — spy — on happenings upstairs on the large multi-picture video screen. Three men clad in slim black suits unfurled muscular, manic motion exploding along the cubicle corridor with bursts as legs and arms flung akimbo. The pressure cooker feeling of too much paper, too much movement, too many people, and sounds in the constrained space felt like a bad day at the office. Musicians Daniel Frankhuizen on cello and synthesizer and Jo Palmer on percussion compounded the atmosphere. “Paper Jungle” resonates with the overstimulated workloads and life loads so many carry, but, even so, with so much to see in such a short time span, it was hard to depart.

After a break the evening included two solos in the Dance Place Theater: percussive tap dancer Gerson Lanza’s “La Migra” explored his Honduran roots and emigration journey, while Malik Burnett’s “In Here Is Where We’ll Dwell” tackled his personal spiritual journey. Both works were personal testimonies to triumph over adversity. Lanza built on ancestral connections to traditional Africanist footwork in bare feet on an amplified wood tap board, pounding out syncopated bass and treble notes before donning brown leather tap boots for a soliloquy in sound. Burnett entered from the lobby hooded — a monk’s robe or a hoodie, in the half-darkness it’s both. Video clips draw on celebrated inspirational personalities from Oprah Winfrey to Amanda Gorman, Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, while the dancer draws himself out to expansive reaches highlighting a spiritual sense of striving for redemption. The work concludes with a slow walk upstairs through the audience to a fading light.

The festival format program, which began at 4:00 p.m., ran through about 5:30 p.m. with a break before the final two works went up in the theater, finishing up shortly after 8:00 p.m. For dance adventurers and dance lovers, this was full immersion; others may not have been so satisfied.

Finally, while this District Choreographer’s Dance Festival heralds a new season, Dance Place’s programming remains truncated. Some months contain just a single run and later in the season multiple weeks are booked, with most presentations being for a single performance rather than a two-show weekend. The organization suffered multiple blows with the retirements of its founding leadership, and turnover in its replacements, along with the ongoing challenges of the pandemic and post-pandemic recovery. Six years along, Dance Place is still finding its footing. It may never be the same. We can only hope the new leadership team remains committed to building on past successes and supporting dance and dancers for generations to come.

This review originally appeared September 13, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

In Memoriam: Alexandra Tomalonis

Dance critic, scholar, historian, educator, and mentor Alexandra Tomalonis died April 7, 2023. I met Alexandra in the early 1980s, when I was a college dance and English major with aspirations to write dance criticism. Shortly after I graduated, Alexandra invited me to write for her self-published magazine — Washington DanceView — which at that time came out quarterly. She took me under her wing, frequently inviting me to join her at Kennedy Center ballet performances. I learned much from her during our intermission conversations with what I called the D.C. critics’ huddle, which included Mike and Sali Ann Kriegsman, George Jackson, Suzanne Carbonneau, Pamela Sommers and Jean Battey Lewis on occasion. I was in awe of these seasoned dance critics and learned much from their writings and their conversations, particularly their recollections of performances I didn’t see or their reports of dance in New York and other cities. Alexandra introduced me to the Dance Critics Association, where I ultimately became president. During the hard 2020 summer of the Covid-19 pandemic, we had an almost weekly phone call where our conversations meandered into family histories, politics, and the art-politic confluence. I wish I had continued those calls when I got busy again.

In April 2013, when Alexandra was teaching ballet history and aesthetics at the Kirov Academy of Ballet in Washington, D.C., then-executive director Martin Fredmann asked me to interview her for the school’s magazine. The article is no longer on the Internet, so I share it below as I reflect on the major influence Alexandra had on Washington’s metropolitan area dance community, as well as on ballet and dance nationally and internationally, through the many students she taught and through her graceful writing. May her love of dance and the written word continue to inspire us.

Alexandra Tomalonis

By Lisa Traiger

Dance critic and author Alexandra Tomalonis has been a fixture at the Kirov Academy of Ballet for a decade now. Over the course of that period, she has taught an estimated 120 to 150 students ballet and art history, aesthetics and the popular favorite “The Great Ballets, 1 and 2,” covering the art form’s 19th- to 21st-century masterworks. But Tomalonis has imparted much more than names, dates and librettos to her students, many of whom have gone on to become professional dancers with companies throughout the world.

Just ask 2010 academy graduate Kiryung (Kiki) Kim, currently a member of the Studio Company of the Gelsey Kirkland Academy of Classical Ballet in New York. “She told us many stories and [a] few stuck with me,” Kim wrote via email recently. She recalled Tomalonis’s story about a recent graduate, an excellent dancer who had auditioned “everywhere” and made it to the final cut at each audition, but had not received a contract, instead ending up at a trainee program. “However, the next year she did not lose hope and auditioned again, getting a corps de ballet contract with a prestigious European ballet company that she wanted to dance in.” Tomalonis, Kim recalled, said that “sometimes things don’t work out, but if you keep working, your time may come, too.” Lesson learned.

As important as the intensive daily program of ballet technique classes and rehearsals is at the school, academics, too, remain a mainstay of what makes KAB so special. Tomalonis, as academic director since 2010, and a teacher here since 2003, has set the course along with the artistic department for a cadre of well-prepared and intelligent dancers, many of whom are making their way in the highly competitive and professional ballet world. Others have gone on to college, some later joining company ranks, others finding work in professions outside the dance field. She believes fully that the best dancers are the most well-educated. Beautiful feet, a high arabesque, and a refined ballet line might get a dancer noticed, but company directors these days want far more – dancers who can think, understand and express are more likely to succeed these days. For Tomalonis that means inculcating her students in ballet history, art history, and the canon of the great ballets.

“These kids will all go to college, we hope,” she said. “I just don’t want them to go at 18, but as dancers they’re going to be dealing with people who went to college.” That’s why her courses cover more than the basics. In high school facts are emphasized, but college, Tomalonis said, is where students learn how to put ideas together, synthesize material and begin to think for themselves. That’s what she hopes to achieve in her advanced classes, particularly Aesthetics and Ballet History. “The last two years I try – and all the teachers here do — to give them more college-like experiences so they can put it together and that’s so exciting.”

“From Ms. Tomalonis, I learned how to learn,” said Carinthia Bank. “And that is more useful than whatever actual facts I might be able to recall.” Tomalonis agrees, premiere dates and other information can easily be looked up. Thinking and responding to deeper questions about why a character might dance a specific way require more thoughtful consideration. Presently a dancer with the Donetsk Ballet of Ukraine, Banks had Tomalonis as a teacher in various summer-program classes from 2006 to 2008, at which time she became a full-time Kirov student.

Tomalonis’s own introduction to ballet was somewhat serendipitous. “I actually took modern dance in college because, first, we had to for a phys ed requirement, and I was also interested in it. But I had not seen any ballet.” She grew up in a family that valued intellectual rigor and enlightened discussion. She studied piano and attended the theater as a child, but her first ballet experience came at about age 26.

“A friend told me Rudolf Nureyev was coming,” she said. “I said, ‘Oh, he’s famous, let’s go see him.’ So we went and the curtain went up on ‘Marguerite and Armand’ … and I loved it.” She went back for more. “With all of my cultural education … I realized I knew nothing about a whole art form. That’s when I started reading and reading and reading.” After a semester in a dance writing class with late Washington Post dance critic Alan M. Kriegsman, she began reviewing for the Post and later her own magazine, Washington DanceView, which eventually evolved into the online DanceViewTimes. She also founded the online discussion boards Ballet Alert! and Ballet Talk for Dancers.

“I didn’t set out to be an historian,” she added, “I just wanted to know how it happened, so I just kept reading.” And in those heady dance boom days of the 1970s, The Kennedy Center, which had just opened, was featuring weeks of ballet companies from around the globe and Tomalonis rarely missed a performance. Soon her fandom grew into something deeper as she explored ballet history. “When I started writing,” she said, “I became more interested in where it came from rather than who was dancing. … I had favorite periods: Ballets Russes, then it was the Royal Ballet, then modern dance. I loved Martha Graham. I love people who try to go back to the beginning and try to do it right, which [Graham] was dong with pre-classical dance forms. And I loved that she took on the Greek myths.”

In her Ballet History course, Tomalonis’s students create a timeline of the art form and she’s always amazed at the creativity her students put into the project – one made a clock, another a tree with roots and branches. She loves to have students compare different versions of a work and study different dancers performing the same choreography, it opens their eyes to understanding the variety and expansiveness in the ballet world. She admitted that her teaching has evolved over her decade at KAB, but her goal has remained. “First I certainly want them to know ballet history. And second, certainly with the Great Ballets, I want them to see how ballet works and looks around the world … [KAB students] are very, very much focused on their technique. And I think they should be, but I think they should be able to see other schools [outside of Vaganova training] and know that a different way of doing an arabesque isn’t wrong. It might just be English. Or that the Paris style is very precise. And Bolshoi is different than Mariinsky.”

Adrienne Bot, a senior this year, said, “The most difficult or challenging aspect of Ms. Tomalonis’s class is that she wants us to be able to articulate not only that we liked or disliked what we read or saw, but why we liked or disliked it.” Bot has had Tomalonis as a teacher from 2011 to 2013 in Great Ballets, Ballet History, and Aesthetics. After graduation Bot has her sights set on landing a company contract where she can continue to grow and learn. From Tomalonis she said, “Her challenge to us is to learn about ourselves, to explore more than just a superficial level of who we are and why something appeals to us or not. It sounds easy, but that is deceptive.”

Kim, a former student, appreciated not only Tomalonis’s depth of knowledge but her insider stories. “She would share many anecdotes about famous dancers, choreographers, and companies,” Kim said, because she spent much time researching a book on Royal Danish Ballet dancer Henning Kronstam (Henning Kronstam: Portrait of a Danish Dancer) and knew many first-hand accounts from dancers in the ballet world. “She gave us the [back] story of [many choreographers’] philosophies on dance.”

Bot added, “Her passion and love of ballet is contagious.” A generation of KAB students certainly thinks so and has benefitted from that knowledge and passion.

Lisa Traiger writes on dance and the performing arts from the Washington, D.C. area and is proud to name Alexandra Tomalonis as one of her mentors.

Originally published by the Kirov Academy of Ballet, April 2013.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Resolute

United Ukrainian Ballet reinvigorates ‘Giselle.’

While their homeland is fighting for its survival, these dancers rallied to create a unified company in just months, and that sense of urgency is palpable.

Giselle

United Ukrainian Ballet

John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Opera House

Washington, D.C.

February 1-5, 2023

By Lisa Traiger

Betrothal, betrayal, and the ultimate forgiveness: these are the themes that shape Giselle into one of the beloved ballets of the Romantic canon. This week exuding resilience, courage, and patriotism, an ad hoc ballet company named the United Ukrainian Ballet re-invigorates this warhorse of a ballet, while demonstrating the indomitable spirit of the Ukrainian people.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine disrupted daily life, including the performing artists and ballet dancers of many of the nation’s opera houses. A ballet dancer’s career is brief, and the inability to train and perform can make it briefer. While many female dancers fled their homeland, amid a barrage of Russian strikes on cities and towns in Ukraine, including its capitol, Kyiv, men were conscripted to fight. Ballet company leaders requested that male dancers be released from military service in order to serve the Ukrainian people through their art. It was granted.

Sixty dancers from Ukraine and around the world, including the National Opera of Ukraine, Doinestk Opera House, Kharkiv National Opera House, and Donbas Opera, to name a few, found their way to the Hague, Netherlands. They have been joined by Ukrainian nationals, among them Cristina Shevchenko from American Ballet Theatre and Kateryna Derechyna from the Washington Ballet.

Together this ad hoc group is breathtaking in conception and physical prowess, rallying to create a unified company, which can take years or decades, in just months, while their homeland is fighting for its survival. That sense of urgency, particularly in act II, is palpable and came to a pinnacle with the bows and curtain calls on opening night. Lead dancers Shevchenko and Oleksei Tiutiunnyk took center stage draped in a vibrant blue-and-yellow banner stating “Stand with Ukraine,” followed by Russian-Ukrainian choreographer Alexi Ratmansky proudly stretching the Ukrainian flag above his head.

The journey to Giselle and the Kennedy Center wasn’t easy but was eased by fortuitous circumstances. A former conservatory-turned-refugee center in the Hague became the haven and home for this new Ukrainian ballet troupe. Last year the company performed in London, Australia, and Paris; this relatively late booking at the Kennedy Center Opera House is the only U.S. performance, and it only happened, according to a Kennedy Center staffer, when the cancellation of the National Ballet of China caused a hole in the ballet series. United Ukrainian Ballet filled the bill nicely.

When choreographer Alexi Ratmansky heard the Ukrainian dancers had taken refuge in the Hague, and they needed a ballet, he didn’t hesitate. The renowned ballet maker and stager, while born in Leningrad, has a Russian mother and a Ukrainian father; his heart, he has said, fully beats for Ukraine.

Ratmansky gifted this ingathering of fleeing dancers a fully realized and reinvigorated version of the 19th-century Romantic classic. The result: a refreshingly compelling evening that draws from historical precedents, which Ratmansky unearthed in research into archival notes and accounts of the ballet that originated in 1841 in Paris. He’s done this before with The Sleeping Beauty, among other classics.

The story of Giselle, a vivacious young woman besotted by Albert (Albrecht or Loys, in some versions), who is a nobleman slumming as a villager, is an oft-done standard in the ballet canon. A stable of the repertoire, Giselle offers up two acts of elegant dancing, along with the pathos of heartbreak when Giselle discovers her suitor isn’t who he claims and is engaged to a noblewoman. As a jilted bride who dies before her wedding, she is resigned to haunt the forest as a ghostly spirit called a Wili. The second “white act” — in the midnight forest — features these ghostly beautifully terrifying Willis, clad in shimmery, bell-shaped gossamer tutus. But their beauty deceives: having been jilted by their fiancés, they haunt the forest to take revenge on single men whom they dance to their doom.

While basing the work on choreography by 19th-century ballet master Marius Petipa, after Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, from the early 19th century, Ratmansky resuscitates what can, depending on the company, be a staid experience aimed at ballet stalwarts. Here he returns to mime passages that often receive short shrift, particularly by American troupes. The codified gestures typically express basic feelings of love, fear, promises to marry, and a passage that presages death. This version allows Berthe (Olena Mykhailova as a fierce helicopter mom), Giselle’s mother to “speak,” miming her worries and the spooky backstory of what happens to young ladies who disobey their mothers’ wishes and court someone in secret. Her sharp gesture as her forearms form a cross pointed to the ground rings true for all the mothers of teenagers over millennia who declared, “Be careful or you’ll find yourself in an early grave.” Sergii Kliachin’s Hilarion, Albert’s rival for Giselle’s attention, broodingly eyes the happy couple as he plots his revenge in order to win Giselle’s heart. He’s a bit like outsider Judd from the Rogers and Hammerstein golden-age classic Oklahoma!

Throughout both acts, small and large details provide for a more compelling Giselle than I’ve seen in decades of dance-going. Some, I’m not sure are fully necessary, like shifting the first-act demi soloists’ variations during the villagers’ variations to a more formalized grand pas de deux structure. For those who know, the four-part grand pas de deux is typically reserved for four-act classical ballets and allows the principal ballerina and danseur to demonstrate their technical virtuosity.

In act II, before the Wilis appear, a bumptious forest scene features a group of drinking buddies out at night for a lark. This “bro” moment, when they toast each other and nearly bump fists, feels like any testosterone-filled Saturday night at the pub. Then Hilarion, and later Albert come upon them. A distant bell chimes midnight and the thought of ghosts makes them scatter. The Wilis, led by the imperious Myrtha, fearsome mean-girl Elizaveta Gogidze, dart and even fly across the stage as they gather to dance under the watchful eye of their tall leader, their translucent veils whisked away as if by magic.

Ratmansky has furthered beautified and given weighted meaning to this white act, through his sensitive staging and floor patterns. The dancers gather, tracing circles and lines and, most notable, forming themselves into the shape of a cross as Giselle’s fresh grave stands to one side. Other intriguing moments include the fight-club-like rounds of dancing Albert is compelled to do at the behest of Myrtha, her gaze steely, her arms crossed across her chest. He is pushed and pulled up and down a diagonal line of Wilis until he collapses in exhaustion.

Shevchenko imbues her Giselle with a vivid personality, she’s girlish but a bit of an adventurer in the first act. Often Giselle is scolded by her mother for her weak heart; this Giselle projects a feisty spirit. It’s no wonder that Count Albert falls for her vivacity. Tiutiunnyk, lean and leggy, is not nearly as caddish as many Albert/Albrechts I’ve come across. His leaps soar, suggesting he’s used to a larger stage than the Opera House, and he’s a fine partner to Shevchenko, guiding her gently into balances. Shevchenko, who returns to the Opera House later this month as Juliet in her home company American Ballet Theatre’s Romeo and Juliet, has a lovely sense of ballon, or rebound, which is perfect for the many versions of the “Giselle step,” a gentle hop on one foot as the other leg opens and closes at the ankle like a hinge. It’s her signature dance — made for a 15-second TikTok video.

The Birmingham Royal Ballet (Great Britain) lent its sets and costumes for this production. Act II’s Wilis shimmer in moonlit colors of palest gray-blue rather than the traditional stark white Romantic tutus, which only Giselle wears.

The new staging of Giselle’s final moments, when she forgives Albert, completely shifted the demeanor of the ballet. Giselle settles herself into a raised berm or hillock at the corner of the stage — resigned to her fate as a jilted woman, foretold by her mother in act I. As Albert approaches her aggrieved one last time, she lifts her head and shoulders, and gestures to him — the sunrise in the background showing the royal retinue arriving — to go to his original fiancée Bathilde. Giselle earns her wings forgiving and releasing her beloved. She will remain a Wili, resigned to a ghostly life only to arise at midnight in the forest.

In a Giselle filled with moving moments, this final gesture was deeply felt and resonated with the resilient and unstinting performances of the company. At the final curtain call, the company stood together, shoulder to shoulder, as the orchestra struck up the Ukrainian national anthem:

The glory and freedom of Ukraine has not yet perished

Luck will still smile on us brother-Ukrainians.

Our enemies will die, as the dew does in the sunshine,

and we, too, brothers, we’ll live happily in our land.We’ll not spare either our souls or bodies to get freedom

and we’ll prove that we brothers are of Kozak kin.

This review originally appeared on DC Theater Arts on February 3, 2023, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Paul Taylor Dance Company Re-Opens Kennedy Center Dance Season with Verve

Familiar works ease us back into the theater on a high note.

Paul Taylor Dance Company

Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 7, 2021

By Lisa Traiger

At this moment, as the nation toggles between light and dark, hope and despair, there was no better choreographer to turn to for the Kennedy Center to inaugurate its 2021–22 (fingers crossed!) dance season. The Paul Taylor Dance Company, founded by the maverick choreographer in 1954, remains an iconic American legacy company. Taylor, who had some DC roots, would sometimes reminisce to me about growing up on Connecticut Avenue, near the National Zoo, and once he regaled me with a tale of peacocks escaping.

The creator of almost 150 choreographic works, Taylor died in 2018, passing on leadership in the company to a former Taylor dancer Michael Novak. In recent years the company, under Novak’s artistic direction, has invited in other American choreographers to share their aesthetic. But this first live program back, after 18 months of Zoom and virtual performances, homed in on two seminal Taylor works:

“Esplanade,” the mostly playful romp, set to Bach’s Violin Concerto in E Major, that the choreographer made as an experiment in 1975. He challenged himself to not use a single “dance” step, relying solely on pedestrian movement, although elevated by the impeccably trained dancers performing the runs, walks, skips, jumps, grapevines, dashes, and crawls as the dancers converge, separate, and regroup at breakneck speed during the allegro.

A master of modulating moods, “Esplanade” serves as a Taylor primer in interweaving light, free-for-all fun with a darker, more contemplative middle section, the largo section of Bach’s Double Concerto for Two Violins in D Minor. Here, the sunny outdoorsy-feeling spaciousness of the first movement contracts. A trio of dancers — two women, one dressed androgynously, reach and try to connect with a man, but a sense of disconnection and despair hangs over the darkened bare stage, while a fourth dancer, as if responding to an alarm, frantically circles this tightly knit trio that can’t reach out and touch one another. Perhaps it’s a family portrait of loss and broken promises.

But again, the music brightens and the playfulness resumes. Taylor’s dancers are beloved for their verve and ability to fall, tumble, and rebound with nary a misplaced bobble. The section where the nine dancers continually run, skip, dive, and tumble to the floor is always breath-catching — someone’s surely going to get hurt — audible gasps could be heard in the audience. But amid the chaos of flying leaps that slide like a runner into home plate, with these continuous falls to the floor, the enduring takeaway is that even as we stumble and fall, we don’t or shouldn’t stay down for long. The world is off-kilter, and has been for a long while, but we’re all still here, making the best in precarious situations. Interestingly, this company of young dancers carries themselves with more lightness and lift. The Taylor style during his lifetime displayed a weightier, more grounded feeling; this current company has just three dancers who have more than five years in the troupe. Most joined in 2017 or after, with the newest hires coming aboard in 2020 and 2021, when even amid the pandemic, virtual classes and rehearsals went on.

“Company B,” the opener, was commissioned by and premiered at the Kennedy Center 30 years ago, in a joint venture with Houston Ballet. I remember that program and the ballet’s dancers, too, had a lighter, lither approach to the Taylor style, but the piece, even with its energetic swing tempos, contains that Tayloresque moodiness, that toggling between light and dark, joy and sadness.

Set to the effervescent songs of the Andrews Sisters, who served as a soundtrack for a generation of American soldiers and civilians during World War II with bright bouncy rhythms and fun, cheesy rhymes. But, as well, there are darker moments and Taylor doesn’t wait for the wrenching war-separating-lovers lyrics. The opening Yiddish inflections of “Bei Mir Bist du Schon” captivate the dancers into a sprightly jitterbug, yet in the background, a silhouette of men slowly marches, kneels, aims rifles, and tumbles. This fore- and backgrounding serves as a perfect metaphor for the American experience of World War II — a war that was fought an ocean away, not on U.S. soil. Throughout “Company B,” that dichotomous sense of joy and sorrow intermingles on stage in foreground and background. There are impish solos and plenty of mugging in “Tico-Tico,” “Pennsylvania Polka,” and “Rum and Coca Cola.” And wrenching moments, too, in “I Can Dream, Can’t I?” featuring Christina Lynch Markham longing for her overseas beau, or in “There Will Never Be Another You” as Maria Ambrose mourns for her fallen lover Devon Louis.

“Company B” ends with a reprise of “Bei Mir Bist du Schon” that is darker, because Taylor reflects back America’s World War II history: that what was bright and flirty on the home front was not what was happening overseas, in Europe. Is the Yiddish song a tell, perhaps, for the Holocaust and Hitler’s extermination of 6 million Jews? Or is it a coincidence that Taylor opened and closed “Company B” with it? He was typically elliptical when discussing his dances, famously answering the question, “What’s the dance about?” with the rejoinder “Oh, 20 minutes.”

In the coming months and years, undoubtedly many artists will craft works that respond to our immediate crises — the global pandemic and racial reckoning. There will be time to ruminate and explore, but at this moment, the familiarity of a 20th-century master choreographer feels just right to ease us back into the theater on a high note.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts on October 9, 2021, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2021 Lisa Traiger

Bowen McCauley Dance Preps for Final Bow, Gives Penultimate Performance

25th Anniversary Program

Bowen McCauley Dance

Artistic direction and choreography by Lucy Bowen McCauley

Kennedy Center Terrace Theater

May 26, 2021

By Lisa Traiger

As the dance world eases back to stages amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Bowen McCauley Dance was among the first to dip a toe in to test the waters, dancing together on the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater stage before a very limited audience of the company’s friends and supporters. The rest of the audience, including this reviewer, attended virtually.

Lucy Bowen McCauley founded her Arlington-based company a quarter century ago, and with her musical acuity and penchant for balletically flavored contemporary dance technique, it became a mainstay on the local dance circuit and beyond. But just as a dancer’s onstage career is most often measured in years not decades or a lifetime, a dance company, too, can have its limits. At the program May 26, 2021, McCauley publicly announced that this performance would be her company’s penultimate. She’s not closing up shop due to the pandemic pause; in fact, Bowen McCauley shared with me years ago that she didn’t foresee leading her company indefinitely and was considering the best time to choreograph her troupe’s final performance. Twenty-five years felt like the right time. Then a global pandemic happened. So instead of finishing with a virtual production, Bowen McCauley Dance Company will take its last bows in September at the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater.

In anticipation of that finale, McCauley created a new work for the Terrace Theater virtual program, “Trois Rêves,” to Maurice Ravel’s complex three-movement piano score “Gaspard de la Nuit,” based on a bleak poem by Aloysius Bertrand. The dream ballet opens to a trio of women in flowing waves and undulations of movement; arms swirl like anemones and other sea creatures. When they cock a raised bent leg behind (attitude, for ballet aficionados), balancing on the other, an image of seahorses comes to mind. Later the men join, yet dancers never meet; all their interactions are safely distanced. The second movement, “Le Gibet,” or gallows, proceeds slowly, steadily, relentlessly as Dustin Kimball, in black down to a pair of leather gloves, plods in. As the specter of death, he lashes his arms toward the grounded dancers. They succumb. Then a white-clad angelic figure (Justin Metcalf-Burton) enters; a battle of life forces ensues like a galactic faceoff as the two never make contact. The nightmarish sequence ends with Death in a moment of morose contemplation, yet a noose drops from above. Death prevails.

The final section lightens the mood with quick-footed, playful dances of nymph-like creatures coursing around a pajama-clad sleeping figure. Bright and spirited, the women leap with catlike grace, their silky dresses floating up around them, while the men cartwheel and squat like frogs. They gambol and scamper stalking the restless sleeper with frolicking abandon. “Trois Rêves,” expertly played by pianist Nikola Paskalov, the company’s music director, demonstrates Bowen McCauley’s sensitivity for and love of challenging 20th-century classical scores that suit her balletically inspired movement language.

The program opened with 2019’s “Dances of the Yogurt Maker,” a lovely abstraction drawing on elements of swirling and churning momentum that I imagine are involved in making yogurt. The score by Turkish composer Erberk Eryilmaz also provides Middle Eastern flavor. The dancers move through shapes hinting at Turkish architectural elements — arms raised above their heads palms together allude to Ottoman arches or the onion domes of minarets. Flexed wrists and bent elbows create curlicues and broken lines as a nod to calligraphy and curvilinear arabesques — the arcing swirls of Middle Eastern design not the ballet pose.

Bowen McCauley honored two longtime BMDC dancers: Alicia Curtis — 14 seasons — and Kimball — 15 seasons. The previously filmed duet from the choreographer’s 2015 work “Victory Road,” with a country-rock accompaniment by Jason and The Scorchers, showcased the dancers’ artistry and their valuable contributions to the company.

The resilience of the company and its dancers was evident in the strength of the well-rehearsed performances as well as the mindfulness to ongoing pandemic concerns. For both live works, the dancers wore masks, and Bowen McCauley adjusted any choreography that required physical contact in “Yogurt Maker”; thus no lifts or partnering occurred. Choreographed while following COVID-19 social-distancing restrictions, “Trois Rêves” featured seven dancers moving expertly and connecting and interacting without ever making any physical contact to comply with COVID safety regulations.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts on June 2, 2021, and is reprinted here with kind permission.

© 2021 Lisa Traiger

‘Romeo and Juliet’: Lovers Are Teens in Juvey

Romeo and Juliet

New Adventures

Choreographed by Matthew Bourne

Kennedy Center in partnership with Center Theatre Group’s Digital Stage

On Demand February 19-21, 2021

“For never was there a tale of more woe than that of Juliet and her Romeo.”

By Lisa Traiger

Who doesn’t know the tragic ending of star-crossed lovers Romeo and Juliet? Yet we continue to be besotted by the Shakespearean tragedy. Choreographer/Director Matthew Bourne’s 2019 restaging in movement follows the bones of the original story, but updates and re-envisions aspects reflecting contemporary societal problems and generational rifts. This production, filmed in exquisite detail by Ross Macgibbon, also borrows from West Side Story’s trope of delinquent youths, and homes in on issues of abuse, neglect, violence, and overmedication of teenagers.

Bourne has become a master of reinventing classics that speak to today’s audiences. He reconfigured the pinnacle of classical ballet, Swan Lake, with a muscular all-male corps de ballet and an embellished plot that makes Siegfried’s quest one of discovering his sexuality, not finding a princess. He set Cinderella during the London Blitz, with bombs and fires and a prince with PTSD. In an all-dance-theater version of Edward Scissorhands, he took a tale of horror and love and made it into a haunting elegy to the outsider. In every Bourne work, he utilizes his cadre of exquisitely trained actor-dancers who move with supreme ease through the warp and weft of his choreographic permutations to weave a compelling and pulse-raising tale.

This filmed version, which was available for viewing on the Kennedy Center website via a Vimeo link, fares quite well in the new virtual performance world dance and theater companies are still acclimating to. Bourne, an OBE with the official title of Sir in his native England, has spoken many times (including to me) of his love for classic Hollywood musicals as a progenitor to his evolution as a choreographer. That shows in the often cinematic methods he uses in productions, including flashbacks and flashforwards, dream scenes or dreamlike sequences, and harsh realism, as well as a touch of Chaplinesque comedy on occasion. In any case, this Romeo and Juliet, filmed before an audience and with multiple cameras at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, is itself like a complete artistic endeavor, not merely a pandemic afterthought recording with a camera plopped in place in an empty theater.

The piece opens, as other Bourne works have done, with the final snapshot: the young couple wrapped in a heart-shaped embrace. As the camera focuses in, it becomes apparent that their closed eyes aren’t sleep and those dark patches on their white costumes are blood. Then the incongruity of a school bell shatters the silence as the curtain reveals a stark white-tiled space surrounded by wire fencing and catwalks above. A sign reads: “Verona Institute.” A corps of young men and women enter in lockstep as Prokofiev’s score punctuates the silence. Clad in white uniforms and Keds, they form regiments as they parade like a doomed battalion of surly teen recruits. We see formidable Nurse Ratchett types dispensing pills and an ineffectual doctor in a frantic group therapy session. Verona Institute is a somber and frightening juvenile correctional facility and an imposing uniformed guard — imposing Dan Wright as Tybalt — keeps everyone in line.

In this Spartan Verona penitentiary, the conflict is not familial but generational: the teens rebel against the discipline and punishment meted out by the adults. A pair of wealthy, uninvolved parents drags a reluctant Romeo (Paris Fitzpatrick) — hyperactive, fresh, and sullen — in for admittance. But not until the parents increase their check is the lad let in. Enter Mercutio (jocular Ben Brown) and Balthasar (Jackson Fisch), who strip him out of his schoolboy jacket and tie and into the uniform.

Bright auburn-haired Juliet stands out from the phalanx of teen girls marching through their paces in her combination of deep longing, delicacy, and a sense of inner toughness. Tybalt, who towers over the petite Cordelia Braithwaite as Juliet, uses and torments her — an off-stage rape is suggested. The star-crossed pair meet at a boy-girl dance arranged by Reverend Bernadette (Daisy May Kemp), who is kindly but as ineffectual as her forbear Friar Lawrence.

The passionate duet captures the young lovers embracing with the desperation that only teenagers feel. They tumble into each other’s arms and share what Bourne calls possibly the longest kiss in theater history and it feels intoxicating. Oh, to be young and in love… It proves a breath of fresh air in this colorless world designed with foreboding clarity by Lez Brotherston. As in other productions, like Swan Lake, Bourne goes to the source score, in this case Prokofiev’s with its marches, waltzes, and swooning flourishes. This version features a new orchestration by Terry Davies that sometimes uses different instrumentations and sometimes snips and tucks to the score. It lends a new nervous energy at times to this Verona’s stolid environs.

The fight scene eschews swashbuckling swordplay for hand-to-hand combat, guns and knives. It plays out more like West Side Story’s Dance at the Gym, as a drunken Tybalt stumbles in to see his chosen Juliet enamored of Romeo. With the group enraged, together they take Tybalt down — an outcry against their tormentor. Romeo, though, is the one with blood on his hands. As they struggle with the severity of their deed, we see Romeo and Juliet writhe, emotionally distraught over what they have witnessed and wrought. The ending is as blood-drenched as expected as the pair — Romeo, then Juliet — die their dramatic and dreadful deaths.

As the curtain falls, they lie alone in that same heart-shaped opening embrace, bloodied and battered.

In updating Shakespeare’s tragedy for our time (or really 2019’s pre-pandemic period), Bourne allows the tale to embody new forms and pose new questions: about how our supposedly highly developed society raises and cares for troubled teenagers with overmedicalization and diagnosis of behavioral problems, and also about sexual and physical harassment and abuse. This isn’t the first time Bourne has touched on either and we’ve seen mental institutions in his works before. This time though he’s set forth some thought-provoking issues that are mostly kept behind closed doors — institutional care for the mentally ill. Not a topic one would expect from a dance company.

Bourne has again reinvigorated a classic to feel consequential right for now.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts on February 23, 2021, and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2021 Lisa Traiger

Sergeant Pepper-mania

Mark Morris Dance Group

Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater

Washington, D.C.

November 14-16, 2019

By Lisa Traiger

The choreographer takes his inspiration from music. In his 40-year career as a dancer and dancemaker, he has created more than 150 works. Music has been his constant impetus and companion in his creative process. In performance, he insists on bringing his own music ensemble to accompany the dancers.Mark Morris dances are emphatically watchable, easily digestible, eccentric, and smartly witty. He so proficiently pairs music and dance, costume and set — with a cadre of collaborators — that it’s hard to have a bad night at a Mark Morris Dance Group performance. This is most often due to the deep musical and creative bond he has with long-time musical collaborator Ethan Iverson.

From his gorgeously lyrical masterpiece (L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato ) to the archly sardonic (The Hard Nut, his version of The Nutcracker) to wildly dramatic (Dido and Aeneas), the musically glorious (Falling Down Stairs), the intellectually bracing (“Grand Duo”) and the wicked fun (his very early “Lovey” danced to the Violent Femmes), Morris’s best pieces compel the body to sing, and the movement, steps, formations, phrasing appear as if they were born just for a particular piece of music.

Thus, when he was approached to make a piece to the Beatles, he didn’t play it straight and just set dancers in motion to the sterling and singable recordings of the Fab Four. The commission offered by the City of Liverpool asked for a dance to commemorate the Beatles’ groundbreaking Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album on the occasion of its 50th anniversary in 2017. The hour-long work, now on a North American tour with the choreographer’s eponymous Mark Morris Dance Group, is currently on stage at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theatre, where it’s awash in accolades from a boomer audience that can’t get enough of the idea of high-brow dancing to the Beatles.

And the vividly colored, smartly cut early 1960s costumes, thanks to designer Elizabeth Kurtzman, and Johan Henckens’ bronze crinkled mylar set — a nod perhaps to Warhol’s “Silver Clouds,” which populated Merce Cunningham’s “Rainforest” — allow Morris’s clean, simple choreographic choices to shine.

In fact, not once is a recorded vocal from John, Paul, George, or Ringo heard. Iverson has rearranged several of the album’s iconic songs — the title track, “With a Little Help From My Friends,” and “When I’m Sixty-Four” — for an ensemble of six playing sax, trombone, piano, keyboard, percussion, and the electronic space-agey theremin. If you know the album — and anyone born before 1967 must know at least some of it — you’ll hear baritone Clinton Curtis sing a few standards in a mostly non-Beatlesque way. The others? You just have to sing along in your head as the music plays.

On additional sections of the score, Iverson riffs on musical ideas of the period that may or may not have influenced the Beatles. Iverson’s musical addendums peppered into the 13 sections include an adagio; an allegro drawing from an offhand trombone phrase in “Sgt. Pepper”; a scherzo inspired by Glenn Gould, Petula Clark, and a chord progression from the album; and a cadenza that reflects the Beatles’ references to European classical music. They are a nifty way to avoid treacly nostalgia while still honoring the innovative band’s contributions.

The opening notes of the piece strike the final chord on the album, a familiar sound for those who have listened to it. The opening choreography features an unwinding clump of dancers that spirals outward filling the stage with a jumble of bold jelly-bean colors — vibrant yellow, tangerine, aquamarine, grape, and hot pink tailored sharply into mod slacks, skirts, turtle necks, and jackets. A little skip-hop step with the arms carefully placed reflects a walker’s gait — the walk across Abbey Road maybe? The company of 15, plus five apprentices, imbues these introductory phrases with a heightened naturalness as their legs pierce the air, arms slicing, palms outward, opened to the audience.

After that initial unwinding moment, the “Magna Carta” section introduces historic figures who make an appearance on the colorfully iconic album cover — from Albert Einstein to Marilyn Monroe to bluesman Wilbur Scoville to boxer Sonny Liston — at each name, a dancer jogs in and takes a pose suggestive of the personality of the figure.

Morris cares little for traditional virtuosic tricks. In fact, his technique is closer to that of founding mother of modern dance Isadora Duncan’s runs, skips, jumps, and hops than the codified virtuosity of either ballet or mid-century moderns like Martha Graham and Paul Taylor. His early training in Balkan folk dances also shows in circle formations, hand-holding pairs, and short lines of dancers, linked and maneuvering in unison.

In Morris’s works a sense of humanity prevails. Yet, the company has changed over time, from a mixed-bag bunch of highly proficient dancers of various heights, body types and backgrounds, to today’s company, which is not necessarily less diverse, but its members are far more similar physically. Everyone is trim, with long legs and an aesthetically pleasing dancerly quality, you can see their ballet backgrounds in the less weighty earthy attack. It makes for a more uniform, although far less interesting looking company. Morris still prizes dancers who are fully themselves on stage and who strive to emulate the human condition in performance.

The evening — like much of Morris’s choreography — plays astutely with theme and variation. Morris enjoys having dancers hold hands, link arms and march or walk in mini regimental rows, four abreast, a nod to the Fab Four. In a series of lovely adagios, one partner in a male-female or same-sex couple lifts the other, whose legs stick straight down in a modest straddle, toes pointed. It’s a simple but distinctive motif. Other repeated phrases include some small traveling skips, skitters and leaps, a big bursting jump with arched backs — cheerleader-y — and some simple turn sequences. Morris shuffles and reshuffles these motifs in ways that make the viewer feel smart — “Oh, yes, I saw that before. I see what you’re doing here” — using a different structure, formation, number of dancers or even sequential or canonic counts.

Morris also winks at the psychedelic era by putting his dancers in mirrored sunglasses on occasion — those “kaleidoscope eyes” from “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” and with some moments late in the work, he lets them loose for free form movement. But the work is conscientiously structured, not improvised. Late in the piece, as “Penny Lane” — not on the album, although originally written for “Sgt. Pepper’s” — plays, the dancers enact an old-fashioned pantomime to the lyrics — getting into a barber’s chair, driving a car, offering a queenly smile and wave, etc. Audiences enjoy the humor and again see the Morris style at work. Other references he throws in might be less obvious such as the mudra, or Indian hand gesture of thumbs up used in the Indian dance form bharata natyam. But for Morris it reflects his love for and study of Indian classical dance. There are plenty of other “Easter eggs” in any Morris work; Pepperland is no exception.

Interestingly, as tuneful and musically interesting as Pepperland is, especially if you read the composer’s program notes, the piece doesn’t come close to a Morris masterwork. The choreographer must love the music completely to attain such a sublime aesthetic level. He’s created dances to Mozart, Britten, Purcell, Bach, Prokofiev, as well as country music, punk rock, Indian ragas and Azerbaijani mugham songs, to name a very few, so a bit of Beatles is no stretch for his rangy musical tastes. But Pepperland simply doesn’t sing in the way his best works can. It doesn’t feel like Morris is all-in. Choreographically, the work is as adept as any of his most recent, showcasing the strengths and talents of his well-honed company, his unparalleled skill in structuring dances that move easily. While it’s unfair to expect a masterpiece every season, Pepperland feels more like an assignment completed: Liverpool wanted a Beatles ballet? Well, Morris went ahead and delivered one.

Finally, for all the bright colors and the tuneful Beatles songs, the oft peppy, upbeat dancing, the whirl of shifting musical and costume colors, Pepperland emanates a surprisingly sober, even somber, tone behind those mirrored sunglasses the dancers wear. The initial opening clump, turns back in on itself at the end, the dancers collapsed, exhausted, overcome as the music rumbles. When asked why he had sad sections in the piece during the post-show discussion on opening night, Morris was, as usual, sharply glib: “Well, it’s a fucking sad world, that’s why.” Then he waved goodnight, tossed his scarf over his shoulder and swanned off.

Photos courtesy The Kennedy Center, top by Gareth Jones, middle by Mat Hayward,

bottom by Robbie Jack.

This review originally appeared on DC Metro Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2019 Lisa Traiger

Farewell

The Suzanne Farrell Ballet

Forever Balanchine Farewell Performances

Kennedy Center Opera House

Washington, D.C.

December 7-9, 2017

By Lisa Traiger

Forever Balanchine, the program at the Kennedy Center December 7 through 9, 2017, heralded the final performances of the Suzanne Farrell Ballet. It occurred during an ignominious moment for the ballet world: New York City Ballet, the company founded by Farrell’s artistic mentor, was awash in accusations related to the behavior of its artistic director, Peter Martins, Balanchine’s chosen successor — and a frequent Farrell partner during their illustrious performing careers.

Farrell built her ballet company from scratch, under the auspices of modest support, financial and otherwise, from the Kennedy Center, with the intention of preserving and resuscitating Balanchine dances not often performed. Over the company’s 17 years, there have been ups and downs in what has essentially been a pick-up troupe with an annual Kennedy Center run (typically at the smaller Eisenhower Theater) and little else — no significant touring, no new commissions, no permanent home for rehearsals. Some dancers kept their “day jobs” with other companies, while others put all their stock in Farrell, even though they only rehearsed and performed a couple of weeks annually in some years.

This set up often resulted in a rag-tag feel to the company. Time and again it wasn’t rehearsed quite enough to tackle the intricate physical and musical demands of some of Balanchine’s more obscure works. Audiences regularly suffered second-rate performances for a chance to revel in the aura of a brilliant muse and how she molded and shaped her selective repertory.

But the company pulled out all the stops for its final performances in the center’s Opera House, at long last living up to the Farrell-Balanchine legacy. The company of 43 dancers appeared well rehearsed, but more auspicious, they truly danced together, bringing breath and soul to the music — accompaniment provided by the Kennedy Center Opera House Orchestra under the baton of Nathan Fifield. Both long-time Farrell dancers — Natalia Magnicaballi, who has danced with Farrell from the start, Heather Ogden, and Michael Cook, among others — and soloists and a corps de ballet of well-trained and finely tuned dancers would have, alas, during a different time, made this a company to watch, rather than one to eulogize.

As hard as it is to build a ballet company from scratch, no one had better materials than Farrell. She spent more than two decades as Balanchine’s muse, starting her career as a coltish teenager and maturing to a beloved embodiment of the Balanchinian aesthetic. Her notable musicality, her lithe line, her dramatic expressiveness, and her daring on stage captured the hearts of many. As artistic director, she made it her practice to revive overlooked Balanchine repertory. Among the ballets she reinstated, “Gounod Symphony” (1958) provided a glimpse at some less-seen but lovely patterns and steps-nestled-within-steps. Thirty dancers surround and weave around a central couple — Magnicaballi and Cook. The original pink and yellow costumes have been redesigned. Holly Hynes’s chic black or white strapless bell-shaped dresses give those kaleidoscopic floor patterns new vivacity: they’re clear, crisp and smartly modern and the black-and-white palette is an artful nod to the black-and-white practice clothes Balanchine sometimes used to replace tutus.

“Meditation” was the first ballet Balanchine made for Farrell and she owns the rights to it — a gift to her from its creator. A love poem in movement and music (Tchaikovsky), the ballet begins and then ends with a man (Kirk Henning on opening night), alone on stage, his head in his hands. An apparition, the ballerina, enters. Elisabeth Holowchuk is not quite the visionary spirit the ballet requires, but as the brief work concludes, we get an inkling of the intense passion that Balanchine felt for his then-young muse who inspired this work. It’s a love unrequited, but not unexpressed, in this ballet. The dancing alludes to heartbreak as Holowchuk and Henning entwine, their hands clasping, then he supports her in arabesque. But, ultimately, she backs away into darkness; he remains, bereft.

The opening night program began with “Chaconne,” from 1976. At its premiere Farrell danced the duet with Peter Martins. Here Heather Ogden and Thomas Garrett took some time to warm to each other and to the audience. The ballet has a split personality. The opening corps de ballet section features eight women, their hair loose, wearing flowing skin-toned chiffon — resembling Grecian priestesses. The couple returns for a more formal duet, and the rest of the ballet is danced in sky-blue tutus. The ballet’s title alluded to French court dance, and the second part contains courtly underpinnings in its classical structures. Farrell first brought this work into the company repertory in 2002 and revived it in 2007. This performance showed a strengthened corps and soloists over prior performances.

“Tzigane” was also created for Farrell, but after her return to New York City Ballet in 1975 following a hiatus. No longer an ingénue, Balanchine showcased his mature ballerina with a sultry entrance: a slow walk punctuated with gypsy-like flourishes of her hands. Magnicaballi has the spice and verve to heat up the Ravel score, parse out some czardas-like steps and attract her partner Cook. It’s a brief work — just nine minutes — but watching Magnicaballi interpret the Ravel violin solo, then backed up by a corps of four women and four men, hinted at the power and sex appeal that Farrell must have imbued in the role. Magnicaballi was steamy and Cook stalked her with ardor, but moments felt more like embers than flames.

Over her long career as a dancer, educator and artistic director, Farrell has received numerous accolades and awards, but she had not received acknowledgement for her contributions to her adopted city, Washington, D.C. That came December 7, when the Pola Nirenska Award was presented to Farrell in honor of her lifetime achievement in dance. Born in Poland, Nirenska escaped the Holocaust and eventually settled in Washington, D.C., where she became a notable matriarch for modern dance in the region. The honor puts a stamp of finality on the 17-year presence the Suzanne Farrell Ballet had in Washington, noting her contributions to the cultural life of the city through her illustrious dancing, teaching and artistic direction.

Above: “Gounod Symphony,” The Suzanne Farrell Ballet Company, choreography by George Balanchine, photo: Paul Kolnik

This review originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of Ballet Review. To subscribe, visit Ballet Review here.

© 2018 Lisa Traiger

leave a comment