New Season: New Hope?

District Choreographer’s Dance Festival

Dance Place, presented at Edgewood Arts Center, Brookland Arts Space Lofts Studio, Dance Place Arts Park, Dance Place roof, offices, and Cafritz Foundation Theater

Choreography: Kyoko Fujimoto, Dache Green, Claire Alrich, Shannon Quinn of ReVision Dance Company, Gerson Lanza, Malik Burnett, and Colette Krogol, and Matt Reeves of Orange Grove Dance.

Washington, D.C.

September 9 – 10, 2023

When Dance Place opened its season each September, it heralded a surfeit of dance performances for the next 11 months. In fact, the nationally known presenter for decades offered up live dance performances across genres from modern to African forms, tap, bharata natyam (a classical Indian form), hip hop, flamenco, performance art, post-modern, raks sharki (belly dance), salsa rueda, stepping, even contemporary ballet, to mention just a few. Dance lovers could be assured of a show nearly every weekend of the year from September through June, with a smattering of performance options spread across the summer. Most years during its heyday, Dance Place presented between 35 and 45 weeks of dance annually, from both regional companies and national and international artists. Among those were first D.C. performances (pre–Kennedy Center invitations) from David Parsons Dance, Urban Bush Women, Margaret Jenkins Dance Company, Rennie Harris/Puremovement, Blue Man Group, and dozens of others. And along with well-curated programming, the organization offered professional and recreational studio classes in modern dance, West African dance and other forms, and a free summer arts camp for neighborhood children.

The feat, presenting more dance annually than the Kennedy Center, happened under the indefatigable visionary leadership of founding director Carla Perlo and her co-director Deborah Riley. Since they stepped away from leadership in 2017, the nationally renowned organization has struggled to find its new identity under two different artistic directors, an acting director, a global pandemic, and presently little institutional knowledge regarding the organization’s outsized influence in the dance world.

But season openings always offer a fresh opportunity to hope.

The 2023/24 season marks Dance Place’s 44th year. September 9 and 10, the organization chose to continue a tradition of showcasing locally based artists in new and recent works, which dates back to the Perlo and Riley era, and “post-pandemic” Christopher K. Morgan named the season opener the District Choreographer’s Dance Festival. This year, Dance Place and seven choreographic artists showcased not only their works but also the studio, performance, and space assets the organization manages and has access to along 8th Street NE, hard by the Metro and railroad tracks, just a short walk from Catholic University.

The afternoon began at Edgewood Arts Center, a community room used for weddings, parties, classes, and the like. Choreographer Kyoko Fujimoto, who also holds a Ph.D. in electrical engineering, fashioned a contemporary ballet quartet featuring point work and lifts, punctuated by the angularity of 90-degree elbows and knees — perhaps an ever-so-slight nod to Balanchine’s mid-20th-century neo-classicism. The work, “into the fields,” was meant to recall the experience of a medical MRI. That was evident in the horizontal crossings of single dancers rising and falling like pointed peaks and valleys of a heart monitor readout. It could also be heard in Caroline Shaw’s music from “Plan & Elevation” and another musical sequence from V. Andrew Stenger and Fujimoto. The stark black biker shorts and white tops provided an ascetic look for dancers Sara Bradna, Ian Edwards, Max Maisey, and Sophia Sheahan.

The audience was then led down the street to a Brookland Arts Space Loft studio for performer/choreographer Dache Green’s “Evolution(ary).” In the tight, bare studio, Green, long, lean and powerful, struts forward in chunky black heels, jean shorts, and an olive green trench coat. Viola Davis’ resonant voice is heard in her famous 2018 speech for Glamour magazine: “I’m not perfect. Sometimes I don’t feel pretty. Sometimes I don’t want to slay dragons … the dragon I’m slaying is myself …” To that, and then to a Beyonce-heavy score — “I’m That Girl,” “Church Girl,” “Thick,” “All Up in Your Mind,” peppered with other artists like Kentheman, Inayah Lamis, and Annie Lennox and the Eurhythmics — Green grabs center stage like a model on a catwalk, owning the space and moment as he poses, struts, bumps and grinds, vogues and twerks, all the while lip-syncing. It’s a public and private confessional about discovering and owning one’s personal story with power and self-love, acceptance, and being fierce.

Back outside in the partly cloudy afternoon, if one didn’t look up, you’d miss ReVision Dance Company’s Amber Lucia Chabus and Chloe Conway, clad neck to ankle to fingertips in highlighter pink and highlighter green respectively, poking a jazz hand, leg, or foot out from the Dance Place Roof. Choreographer Shannon Quinn let her two dancers loose on the roof to play with each other and with the viewers two stories below. I recalled film and photos of choreographer Trisha Brown’s 1971 “Roof Piece” and loved this nameless piece d’occasion all the more for its nod to post-modern dance history, while not taking itself too seriously, including playful moments and silly mime as the duo stepped down to disappear, then pop up seconds later in another location.

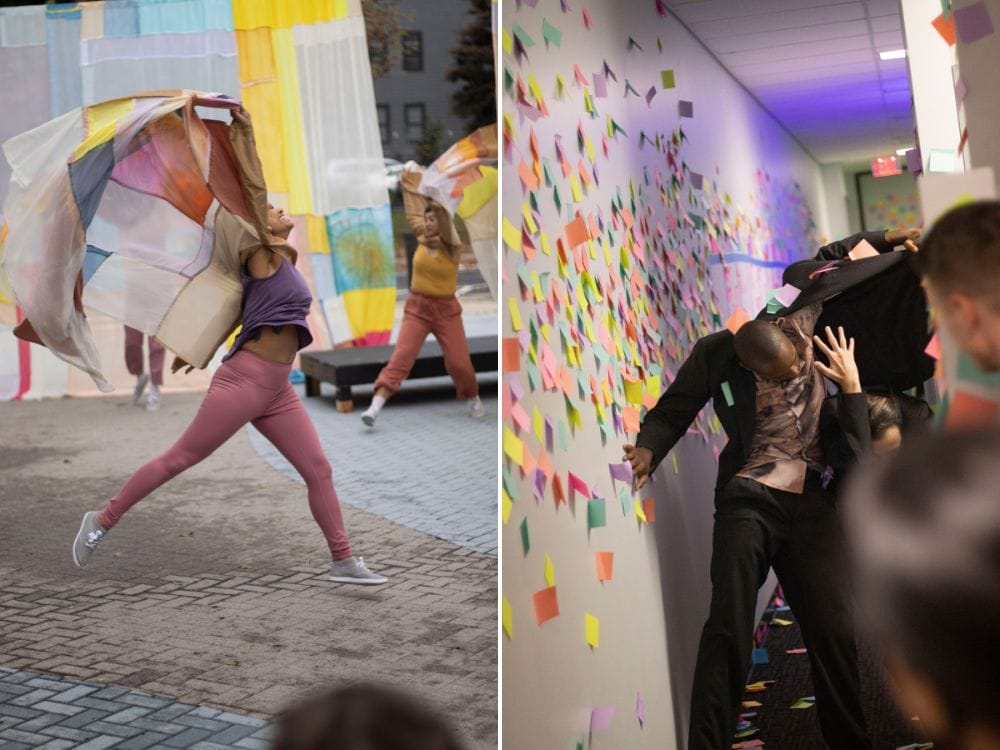

Claire Alrich’s “scenes from an elevator ascending” spread out on the Arts Park, a former city easement of land Perlo developed into a multi-use space for the community to congregate between Brookland Arts Lofts and Dance Place. With a set of stitched-together curtain-like panels and flowing cape-like tunics in mauve, mustard, and cantaloupe colors designed by Alrich and Mara Menahan, the three dancers stretch their arms to work the expanse of the costume. The work feels like an organic transformation in process. I was reminded of the caterpillar-chrysalis-butterfly cycle, particularly as the dancers gently left the space walking away down Kearny Street as Santiago Quintana’s score faded.

“Paper Jungle” was meant to be a ten-minute experiential piece for ten people at a time to walk through the upstairs office cubicles of Dance Place. Technical delays kept groups waiting, but Orange Grove Dance, helmed by choreographic and design partners Colette Krogol and Matt Reeves, is consistently worth a wait. Entering the tightly constricted hallway, walls scattered with Post-it notes, “Paper Jungle” featured dancers Robert Rubama and London Brison joined by Reeves, who at times carried an open laptop on record. Audiences waiting in the downstairs lobby could watch — spy — on happenings upstairs on the large multi-picture video screen. Three men clad in slim black suits unfurled muscular, manic motion exploding along the cubicle corridor with bursts as legs and arms flung akimbo. The pressure cooker feeling of too much paper, too much movement, too many people, and sounds in the constrained space felt like a bad day at the office. Musicians Daniel Frankhuizen on cello and synthesizer and Jo Palmer on percussion compounded the atmosphere. “Paper Jungle” resonates with the overstimulated workloads and life loads so many carry, but, even so, with so much to see in such a short time span, it was hard to depart.

After a break the evening included two solos in the Dance Place Theater: percussive tap dancer Gerson Lanza’s “La Migra” explored his Honduran roots and emigration journey, while Malik Burnett’s “In Here Is Where We’ll Dwell” tackled his personal spiritual journey. Both works were personal testimonies to triumph over adversity. Lanza built on ancestral connections to traditional Africanist footwork in bare feet on an amplified wood tap board, pounding out syncopated bass and treble notes before donning brown leather tap boots for a soliloquy in sound. Burnett entered from the lobby hooded — a monk’s robe or a hoodie, in the half-darkness it’s both. Video clips draw on celebrated inspirational personalities from Oprah Winfrey to Amanda Gorman, Maya Angelou to Toni Morrison, while the dancer draws himself out to expansive reaches highlighting a spiritual sense of striving for redemption. The work concludes with a slow walk upstairs through the audience to a fading light.

The festival format program, which began at 4:00 p.m., ran through about 5:30 p.m. with a break before the final two works went up in the theater, finishing up shortly after 8:00 p.m. For dance adventurers and dance lovers, this was full immersion; others may not have been so satisfied.

Finally, while this District Choreographer’s Dance Festival heralds a new season, Dance Place’s programming remains truncated. Some months contain just a single run and later in the season multiple weeks are booked, with most presentations being for a single performance rather than a two-show weekend. The organization suffered multiple blows with the retirements of its founding leadership, and turnover in its replacements, along with the ongoing challenges of the pandemic and post-pandemic recovery. Six years along, Dance Place is still finding its footing. It may never be the same. We can only hope the new leadership team remains committed to building on past successes and supporting dance and dancers for generations to come.

This review originally appeared September 13, 2023, on DC Theater Arts and is reprinted with kind permission.

© 2023 Lisa Traiger

Erotic

Antithesis: Dance Place Practice

Gesel Mason Performance Projects

Conception and choreography by Gesel Mason

Dance Place, Washington, D.C.

January 6, 2017

By Lisa Traiger

Since one of her first independent performances in Washington, D.C., at Dance Place, dancer and choreographer Gesel Mason has been navigating the taboo and the titillating. She has put a bold face on works that wrestled with race, racism and its deep-rooted role in American history in her A Declaration of Independence: The Story of Sally Hemmings (2001), as well as her ongoing “No Boundaries” project, which gives voice to African-American choreographers in a series of commissioned and revived solos. Mason also has a biting wit: one of her signature solos, How To Watch a Modern Dance Concert or What the Hell Are They Doing On Stage? takes down the sacred cows of 20th-century modernism and post-modernism in dance, with the choreographer’s tongue firmly planted inside her cheek. And, finally, and more than for good measure, Mason has often used her own text and poetry, including the searing “No Less Black,” as accompaniment to her choreography.

On her return to Dance Place, the nation’s capital’s most popular dance performance venue, she converts the black box studio theater into a post-modern burlesque house for her evening-length inquiry into the erotic, and the exotic, of embodied female sexuality. It’s a daring endeavor for Mason, who early in career was a company member of Liz Lerman Dance Exchange until forming her own project-based troupe and production company, Gesel Mason Performance Projects. Over nearly two decades, the dancer/dancemaker has tackled the profane and provocative before in Taboos and Indiscretions (1998) and her later Women, Sex & Desire: Sometimes You Feel Like a Ho, Sometimes You Don’t (2010), when she collected the stories and movements of District-based sex workers for a piece that gave voice to often well-hidden and ignored female stories.

So it was interesting that Mason names her latest work with a less provocative and more academic title: Antithesis. Developed at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she is now an assistant professor, it continues her explorations into personal and public sexuality, the role of the female in society and, an oft unremarkable theme in much American modern dance, personal expression and self-exploration. The piece features a cast of ten, including burlesque dancers Essence Revealed, Peekaboo Pointe and Love Muwwakkil, as well as more traditionally trained modern — or as Mason refers to them, post-modern — dancers (Ching-I Chang Bigelow, John Gutierrez, Kayla Hamilton, Kate Speer and Rita Jean Kelly Burns are among the cast), with a cameo by Mason’s mom, Andrea Mason. The work, in development for nearly three years, brings together these two worlds where the female body is on display, either in the dance studio and concert stage for the modern dancers, or in the strip club and burlesque stage for the pasty-clad performers. In Mason’s purview, it’s a chaotic collision.

With a stripper pole prominently displayed before the studio mirrors, the show begins. Clad in a silky bathrobe Mason serves as emcee, introducing the audience, seated on all four sides, to the ladies. There’s Peekaboo, the taut bleached blonde with an Ultrabrite smile, in her patriotic g-string and pasties. And Love, a virtuoso of the pole, caressing, climbing and sliding on her apparatus like Simone Biles on the balance beam. But there are other more prosaic dancers, whose talent for, say, Quickbooks, savings accounts and bank account reconciliations is lauded as vigorously in Mason’s biting narrative. And on that note it becomes clear that for the next hour the audience is in store for more that so-called tits and ass. Mason has constructed a probing critique of a slice of contemporary eroticism.

Informed by poet and literary critic Audre Lorde’s essay “Uses of the Erotic,” Mason set out to understand the female body as it is seen and used, empowered and comodified, in various public spaces in the 21st century. For Lorde, the erotic isn’t eroticism, particularly not derived from the male gaze that has made women’s bodies objects to be stared at, re-shaped, manipulated, and appropriated. Lorde views the erotic as harnessing female power — that vital physical and spiritual lifeforce that imbues creativity of all kinds on individuals. Eroticism, then, is about knowing oneself truly, and it’s about embracing the chaos of life and living.

Antithesis pursues that idea by mediating between the patriarchal view of the erotic — the specific kinds and shapes of women’s bodies on display for male desire and pleasure. But instead, especially the burlesque dancers demonstrate complete comfort and confidence in their bodies. They own their eroticism, their physical power and the hold they have over the opposite sex in particular. And they revel in it. They perform their unique identities for their own pleasure; the audience is merely along for the ride. The pasties and g-strings? Sure they’re hot and sexy, as are the burlesques and strip teases. But removed from a gentleman’s club or a strip joint and located in a typical concert venue, the performative nature of the dance is transformed from eroticism into commentary on the feminine, the female, patriarchy and wholesale comodification of bodies, whether its pasties or Quickbooks.

Mason then traverses the divide between women in modern and post-modern dance and women who publicly display and sell their bodies. Is there, ultimately, a difference? Aren’t we all for sale? Is there always a price? Is one art and the other commerce or objectification?

One dancer, barefoot, clad in jeans and a lumberjack shirt, rolls on the floor, releases her weight, shifting her dynamics with limber ease, her face an expressionless mask. Then on comes Peekaboo in her stilettos and pasties. She parses through the same movement phrase, her firm, sensual body on display, her bored look recalling a pin-up girl. Context is everything. A fan-kick or split is merely a piece of choreography. It becomes meaningful in performance. It’s the question of who … and where. And, as Mason noted in a post-performance talk Friday evening, each time Antithesis is performed, she considers it site-specific. At home in Colorado, it has been shown in a church, in a strip club, and in someone’s private home. Its re-staging at Dance Place is, she said, unique.

While plenty of female flesh and embedded discourse on the erotic filled the hour, ultimately it felt like Mason and her performers didn’t push far enough. Most believable and most comfortable in their bodies and skin were Essence and Peekaboo and Love. Much was said about how the process challenged the rest of the performers, who worked to allow themselves into new territory, physically and psychically, erotically. As the dichotomous sets of performers merged, late in the show, clad in silky vibrant orange, slacks, dresses, and tunics, Mason returned to her microphone, calling cues for the dancers to physicalize: “hidden,” “surrender,” “play,” “joy,” “chocolate,” “pleasure.” Counting up to ten, the dancers strove to embody in free-form movement those words and ideas, but, like many improvisations, it ended up looking more like moving wallpaper than personal transformation. The dancers, particularly the modern dancers, were still acclimating themselves and their bodies to this new way of thinking and moving — this new erotic consciousness.

One of Lorde’s definitions of the erotic is the “measure between the beginnings of our sense of self and the chaos of our strongest feelings.” That final apotheosis, the melding the dancers into a singular unified force, reached for a semblance of utopianism within chaos. And, yet, as this collision of cultures, of bodies, of dancers, that has been occupying the space and lives of its participants, needs to still push further. Mason, her dancers, and dramaturg, Deanna Downes, have described the work as “messy, gritty, tactile, growling, chaotic, passionate and tender.” Antithesis is, in various measures, each of these, for many in the audience. But, no longer the independent artist of her earlier “taboo” days, Mason is now ensconced in the university, and that has taken a toll on her independent, compelling voice. She appears, alas, to have reigned herself in, becoming more self-conscious. Throughout Mason’s career as a choreographer, provocative, even taboo subjects have been an important part of her body of work, most especially wrestling with and coming to terms with identity issues. She has lost some of her youthful boldness, though, in striving to fit into the academic realm (as many independent choreographers have been doing in recent years). Mason’s latest feels trapped in theory: Lorde’s essay and philosophy has too much hold on her.

Photo credit: Kelly Shroads

© 2017 Lisa Traiger

Published January 8, 2017

2015: A Look Back

For reasons that continue to surprise me, 2015 was a relatively light dance-going year for me. That said, I managed to take in nearly a top ten of memorable, exceptional or challenging performances over the past 12 months.

The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, on its annual February Kennedy Center Opera House visit, brought a program of politically relevant works that culminated, as always, in the inspirational paean to the African-American experience, “Revelations.” Up first, though, was the restless “Uprising,” an athletic men’s piece that draws out the animalistic instincts of its performers. Israeli choreographer Hofesh Schechter, drawing influence from his experiences with the famed Batsheva Dance Company and its powerhouse director Ohad Naharin, found the disturbing core in his 40-minute buildup. As these men, in street garb – t-shirts and hoodies – walk ape-like, loose-armed and low to the ground, their athletic sparring, hand-to-hand combat, full-force runs and dives into the floor, ultimately coalesce in a menacing mélange. Is it protest or riot? Hard to tell, but the final king-of-the-hill image — one red-shirt-clad man reaching the apex of a clump of bodies his first raised — could be in solidarity or protest. And, in a season awash in domestic and international unrest, “Uprising,” with its massive large group movement, built into a cri de coeur akin to what happened on streets the world over in 2015.

The Washington Ballet Artistic Director Septime Webre has been delving into American literary classics and on the heels of his successes with both F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby and Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, in February his fearless chamber-sized troupe unveiled his latest: a full-length Sleepy Hollow, based, of course, on the ghostly literary legend by Washington Irving. But more than just a haunted night of ballet, Webre’s Sleepy Hollow delved into America’s early Puritan history, with a Reverend Cotton Mather character and a scene featuring witches drawn from elements of the Salem witch trials, expanding the historical and literary context of the work. This new dramatization in ballet, featuring a rich score by Matthew Pierce; well-used video projections by Clint Allen; and scenery by Hugh Landwehr; focuses on the tale of an outsider, Ichabod Crane – a common American literary trope. Choreographically Webre has smartly drawn not only on the expected classical ballet vocabulary, but he also tapped American folk dances and early and mid-20th century modern dance influences to expand the dancers’ roles for greater expressivity and storytelling. Guest principal Xiomara Reyes played the lovely love interest, Katrina Van Tassel, partnered by Jonathan Jordan. It’s hard to say whether this one will become a classic, but Webre’s smartly and carefully drawn characterizations and multi-generational arc in his approach to the Irving’s story expanded the options for contemporary story ballets.

Gallim Dance, a Brooklyn-based contemporary dance company founded by choreographer Andrea Miller, made its D.C. debut at the Lansburgh Theatre in April. Miller danced with Batsheva Ensemble, the junior company of Israel’s most significant dance troupe, and she brings those influences drawn from the unique methodology Naharin created. Called “gaga,” this dance language frees dancers and other movers to tap both their physical pleasure and their highest levels of experimentation. In “Blush,” this pleasure and experimentation played out with Miller’s three women and three men who dive head first into loosely constructed vignettes with elegant vengeance. With a primal sense of attack as they face off on the stage taped out like a boxing ring. Miller’s title “Blush” suggests the physiological change in a person’s body, their skin tone and during the course of “Blush,” transformations occur as the dancers, painted in Kabuki-like white rice powder, begin to reveal their actual skin tones – their blush. In so doing, they become metaphors for shedding a protective outer layer to reveal their inner selves.

The Washington Ballet continued its terrific season with the company’s much ballyhooed production of Swan Lake, at the smaller Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in April. It garnered international attention for Webre’s casting: ballet “It” girl Misty Copeland, partnered by steadfast senior company dancer Brooklyn Mack, became purportedly the first African American duo in a major American ballet company to dance the timeless roles of Odette/Odile and Siegfried, respectively. But that’s not what made this Swan Lake so memorable, and mostly satisfying. Instead, credit goes to former American Ballet Theatre principal Kirk Peterson, responsible for the indelible staging and choreography, following after, of course, Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov. He drew exceptional performances from this typically less than classical chamber-sized troupe. The corps de ballet, supplemented by senior students and apprentices, really danced like a classical company. As well, Peterson, who has become an expert in resuscitating classics, returned little-seen mime passages to the stage, bringing back the inherent drama in this apex of story ballets. My favorite is the hardly seen (at least in the U.S.) passage when Odette, on meeting Siegfried in the forest in act II, tells him the story of her mother, evil Von Rothbart’s curse and the lake, filled with her mother’s tears, as she gestures in a horizontal sweep to the watery backdrop and brings her forefingers to her eyes indicating dropping tears. Live music was provided by the Evermay Chamber Orchestra and made all the difference for the dancers, even though the company’s small size meant the act III international character variations were cut. While the hype focused on the Copeland debut, she didn’t own or carry the ballet, and here Mack was a solid, but not entirely warm Siegfried. This Swan Lake truly soared truly through the corps, supporting roles and staging.

June brought the Polish National Ballet, directed by Krzysztof Pastor, to the Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater in lovely evening of contemporary European works. The small company – 11 women and a dozen men – are luscious and intelligent dancers who can captivate in works that push beyond staid classical technique. Pastor’s program opener, “Adagio & Scherzo,” featuring Schubert’s lyricism, twists, winds, and unfurls in pretty moments. There is darkness and light, both in the choreography and in designer Maciej Igielski’s illumination, which matches the shifting moodiness of the score. Pastor’s movement language is elegant, but not constrained, his dancers breathe and stretch, draw together and nuzzle in more ruminative moments, then split apart. In his closer “Moving Rooms” we first meet the dancers arranged in a checkerboard pattern on a black stage, each dancer contained in an single box of light. Using the sometimes nervously itchy score by Alfred Schnittke and Henryk Mikolaj Gorecki, the dancers, clad in flesh colored leotards, used their legs and arms in sharp-edged angles and geometries. But the centerpiece of the evening was a new “Rite of Spring” – yes, to that Mt. Everest of scores by Igor Stravinsky – this one is choreographed by French-Israeli Emanuel Gat. Danced on a red carpet, the five dancers ease into a counterintuitive tango of changing partners, always leaving one dancer as the odd one out. The smooth and slightly sensuous salsa is the basis for the work’s movement sinuous vocabulary, as it quietly builds like a slowly simmering pot put to boil.

Man and machine – or in this case – dancer and computerized robot – meet in Taiwanese-born choreographer and dancer Huang Yi’s 50-minute work. The evening presented in The Clarice’s Kogod Theater, its black box at the University of Maryland in September, provided a merging of art and technology. KUKA, the German-made robot, used in factories around the world to insert parts that build autos and iPads, has become a companion and artistic partner for Yi. Performing to a lushly classical score of selections from Bach and Mozart, Yi, clad in a dark suit, dances with, beside and around the singular movable robot arm sprouting from KUKA’s bright orange base. There are moments of serendipity, when the two seem to be communing in a duet of machine and motion, and others, in the dimly lit work, when each strays off on a tangent – robot and human, may move side by side, or even together, but only one inhabits a spiritual profound space of flesh, blood and breathe. That was my take away from this intriguing experiment in technology and dance. Yi is at the forefront of merging art with new technology and his experimentation – he programmed the robot – is on the cutting edge, but the work doesn’t cut to the quick. Still, orange steel and computer chips don’t trump muscle, bone, flesh and spirit. I would like to see more of Yi’s slippery, easy silken movement, in better light and with living breathing partners.

Man and machine – or in this case – dancer and computerized robot – meet in Taiwanese-born choreographer and dancer Huang Yi’s 50-minute work. The evening presented in The Clarice’s Kogod Theater, its black box at the University of Maryland in September, provided a merging of art and technology. KUKA, the German-made robot, used in factories around the world to insert parts that build autos and iPads, has become a companion and artistic partner for Yi. Performing to a lushly classical score of selections from Bach and Mozart, Yi, clad in a dark suit, dances with, beside and around the singular movable robot arm sprouting from KUKA’s bright orange base. There are moments of serendipity, when the two seem to be communing in a duet of machine and motion, and others, in the dimly lit work, when each strays off on a tangent – robot and human, may move side by side, or even together, but only one inhabits a spiritual profound space of flesh, blood and breathe. That was my take away from this intriguing experiment in technology and dance. Yi is at the forefront of merging art with new technology and his experimentation – he programmed the robot – is on the cutting edge, but the work doesn’t cut to the quick. Still, orange steel and computer chips don’t trump muscle, bone, flesh and spirit. I would like to see more of Yi’s slippery, easy silken movement, in better light and with living breathing partners.

Camille Brown went deep in mining her childhood experiences in Black Girl: Linguistic Play, presented by The Clarice in the Ina & Jack Kay Theatre in October. The evening-length work draws on Brown’s and her dancers’ playground experiences, first as young girls playing hopscotch, double dutch jump rope and sing-songy hand clapping games. On a set of platforms, chalk boards that the dancers color on and hanging angled mirrors designed by Elizabeth Nelson, Brown and her five women dancers inhabit their younger selves, in knee socks, overall shorts, and all the gum-chewing gumption and fearlessness that seven-, eight- and nine-year-olds own when they’re comfortable in their skin. As the piece, featuring a live score of original compositions and curated songs played by pianist Scott Patterson and bassist Tracy Wormworth hit all the right notes as the performers matured and grew before our eyes from nursery rhyming girls chanting “Miss Mary Mack” to hesitant pre-adolescents, fidgeting and fighting mean-girl battles, to teens on the cusp of womanhood – and uncertainty. The work is a vibrant and vivid rendering of the secret lives of the little seen and less heard experiences of black girls. The movement is pure play: physical, elemental, skips and hops, the stuff of recess and lazy summer days. But there are moments of deep recognition, particularly one where an older sister or mother figure gently, carefully, lovingly plaits the hair of one of the girls. Its quiet intimacy, too, speaks volumes.

The dance event of the year was likely the much heralded 50th anniversary tour celebrating Twyla Tharp’s choreographic longevity and creativity. For the occasion at the Kennedy Center’s Eisenhower Theater in November, she pulled together a 13-member ensemble of some of her long-time dancers and some younger favorites – multi-talented performers who can finesse a quick footed petit allegro or execute a jazzy kick-ball-change and slide sequence or bop and rock in bits of freestyle improvisation with equal skill. For the two Tharp did not revive earlier masterpieces, instead she paid a sort of homage to her elf with a pair of new works – “Preludes and Fugues” and “Yowzie.” Each had elements of hat smart synchronicity that Tharp favors, her beloved little balletic passages that she came to embrace after years of more severe post modernism, and her larky, goofy wiggles, scrunches, and witty physical jokes, like pairing the “tall” girl with the shortest guy in the company, or little games of tag or chase and odd-one-out that are interspersed in both works. “Preludes and Fugues” was preceded by “First Fanfare,” featuring a herald of trumpets composed by John Zorn (and performed by the Practical Trumpet society). The two works, one a bit of appetizer, the other the first course, bled into each other and recalled influences of Tharp’s earlier beloved choreography, especially the indelible ballroom sequences and catches of “Sinatra Suite.” “Preludes and Fugues” is as staunch piece set to Bach fugues that Tharp dissects choreographically with precise footwork, intermingling couples, groups and soloists and her eye for the “everything counts” ethos of post-modernism where ballet and jazz, loose-limbed modern and a circle of folk like chains all blend into a whole.

“Yowzie” is brighter, more carefree, recalling the unbridled energy of a New Orleans Second Line with its score of American jazz performed and arranged by Henry Butler, Steven Bernstein and The Hot 9. Dressed in mismatched psychedelia by designer Santo Loquasto the dancers grin and mug through this more lighthearted romp featuring lots of Twyla-esque loose limbs, shrugs, chugs and galumphs along with Tharpian incongruities: twos playing off of threes, boy-girl couplings that switch over to boy-boy pairs, and other hijinks of that sort. The dancers have fun with the work, its floppiness not belying the technical underpinnings that make the highly calibrated lifts, supports, pulls and such possible. The carnivalesque atmosphere feels partly like old-style vaudeville, partly like Mardi Gras. In the end though, both works are Twyla playing and paying homage to Twyla – they’re both solid, smart and well-crafted. They’re not keepers, though, in the way “In the Upper Room,” “Sinatra Suite,” or “Push Comes to Shove” were earlier in her career.

Samita Sinha’s bewilderment and other queer lions is not exactly dance or theater, but there’s plenty of movement and mystery and beauty in her hour-long work, which American Dance Institute in Rockville presented in early December. In a year of no Nutcrackers for this dance watcher, this was a terrific antidote to the crushing commercialization of all things seasonal during winter holidays. Sinha, a composer and vocal artist, draws on her roots in North Indian classical music as well as other folk, ritual and classical music traditions. Together with lighting, electronic scoring, a collection of props and objets (visual design is by Dani Leventhal), she has woven together a world inhabited by creative forces and energies from across genres and encompassing the four corners of the aural world. Ain Gordon directed the piece, which sometimes featured text, sometimes just vocalizing, sometimes movement as Sinha and her compatriots on stage Sunny Jain and Grey Mcmurray trade places, come together to play on or work with a prop, like a fake fur vest or scattered collected chairs and percussive instruments. There were eerie keenings, and deep rumbles, higher pitched vocalizations, cries, exhales, sighs, electric guitar and steel objects banged together, all in the purpose of building a world of pure and unclichéd vocal resonance. It would be too easy to compare her to Meredith Monk and Sinha is far less artistically self-conscious and precious. She is most definitely an artist to follow. Her vision and talent, keen eye and gracious presence speak – and sing – volumes.

© 2015 Lisa Traiger

Published December 31, 2015

Defiance and Strength

Voices of Strength: Contemporary Dance & Theater by Women from Africa

Kennedy Center Terrace Theater

Washington, D.C.

October 4-5, 2012

By Lisa Traiger

There’s nothing subtle or understated about the eight women who comprise “Voices of Strength: Contemporary Dance & Theater by Women from Africa,” two programs that made the rounds of the U.S. on a tour produced by MAPP International this past fall. The two-night stop at the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater proved exhilarating, enlightening, entertaining and frustrating – sometimes at various moments, other times all at once. What these programs were not were forgettable. The comic duo Kettly Noel and Nelisiwe Xaba, from Mali by way of Haiti and South Africa, respectively, makes dagger-like satire of female obsessions with fashion, male-female relationships, power and individuality. What initially appears to be a light-hearted romp about appearances transforms into something far meatier. Slim, chic, turbaned Noel begins Correspondances with her morning ablutions: surveying a closet of dresses and interchangeable black stiletto heels, checking her lipstick, peering critically into a mirror. Xaba enters from the audience, dragging a battered suitcase behind her. She, too, changes her shoes and outfit. They circle each other, warily sizing up the competition. Later, one manipulates a marionette and states, “I am a woman, fragile but strong inside.”

The two relate what money can by: diamonds, petrol, couture, power – unspoken, but not overlooked is the insinuation that they have none of those material goods. Finally, both strip to leotards, Noel calling out in her native French lists of ballet terms, which Xaba furiously tries to execute, undercutting the rarified vocabulary created by royalty into a mishmash of crudely and comically executed steps. The piece ends in a riot of spilled milk. As the Eurhythmics’ “Sweet Dreams” pulses, the two pull on udder-like containers of milk dropped down from the rafters. Correspondances is a messy, uninhibited navigation of the many landmines women – especially African women, they seem to suggest — face – from appearances to the strictures of expectations to serve others to their own desire to assert power in the still male-dominant culture. That they accomplish their task with droll humor makes it all the more engaging.

There was nothing playful about Quartiers Libres by Ivory Coast’s Nadia Beugre. The work is a bold indictment of Western culture, power, and politics – as powerful and unrelenting as Correspondances was fun and goofy. Performed before a shimmering curtain of empty plastic water bottles, designed by Laurent Bourgeios, Beugre, too, breaks the fourth wall. Entering from a seat in the audience, she carries a microphone, whose cord is draped around her, first like a necklace, later, though, it become a noose. There, after singing and meandering, she finds herself in row C near the stage, where she stares down a woman. After moments of silence the onlooker (a plant?) acquiesces and removes the cord, releasing Beugre’s shackles. But the dancer remains bound, in her silver sling-backs and skin-tight dress, which she wears uncomfortably.

After stripping away her costume to gain a semblance of physical freedom on stage later she squeezes herself into a suit made from more water bottles – becoming a prickly, 21st century porcupine – one with an environmental subtext about overuse of plastic bottles. Finally, Beugre gazes unforgivingly at the audience, brusque, eyes narrowed, confrontational, she stands there. Then she crumples and shoves large black plastic garbage bags into her mouth, her cheeks inflating like a chipmunk’s. From the audience as this continues incessantly: occasional giggles of discomfort. The air is tense, charged – will she suffocate? gag? when will she stop? – and, finally, after an interminable wait, she pulls them out then stands, spent. For her bow, Beugre remains defiant, piercing the air with a peace sign. The work hearkens back to both that of politically confrontational performance artists like Holly Hughes and Karen Finley in its bold and unvarnished approach as well as to the post-modernists a generation before them. Interestingly, both pieces feature high heels as an expression of women’s captivity and powerlessness – the stiletto is the new 21st century pointe shoe, perhaps.

Maria Helena Pinto from Mozambique is also defiant, dancing the entirety of Sombra with a bucket on her head, a bold metaphor asserting unequivocally her right to be seen and heard. To a voiceover in French and Portuguese, she navigates a row of upturned buckets, teetering atop them as if walking a tightrope. She straps on a baby carrier, swaying her hips at one point, unleashing a momentary tango at another. Weaving through buckets hanging from the ceiling with no visual cues, Pinto seems invincible, conquering adversity blindly her head trapped in that bucket yet taking each step boldly. Then the fury unleashes, she scatters buckets everywhere, flinging the one from her head. Finally, free we hear, in French, her last plea: “Give me light, look at my face, enlighten me.”

Morocco’s Bouchra Ouizguen brought the raucous and freewheeling Madame Plaza set on four ample women of a certain age, who first appear reclining on divans, staring and languidly shifting positions. More matronly than dancerly, with bellies and full backsides, flabby arms and double chins, these women have little apparent technical dance training, but a lifetime of experiences filter through in their performance. This harem-like setting becomes a place of calm repose and of refuge, as well as a place to act out and fantasize about relationships. They uses their voices to chant – sometimes it’s a singsong melodic phrase, or a vocal alarm, other times it becomes laughter.

They experiment rising, falling into the floor and rolling, using their hefty weightedness to full effect. At one point one of the women dons a man’s jacket and fedora and a couple acts out a male-female scenario, but they emasculate the “man” who promenades one of the other women around, body to body, appearing at once intimate, entirely natural, and awkward. The piece meanders, time expanding, seeming to stand still, ultimately ending as it began, with the women seated on the divans. Madame Plaza is a reclamation of a woman-centric space as a place to be safe, nurtured, protected, and free to explore creativity and imagination away from the male gaze. Even with its naïve and outsider approach to choreography and structure, the piece is still a powerful reclamation of the female harem, not as a place of isolation and oppression, but as a way for women to congregate and create a community and assert their voices.

Each of these works provides a glimpse into the issues and problems that women across the continent of Africa may face. These women have an outlet: dance, which speaks provocatively and with uncanny directness. David Landes, a Harvard University professor and author of The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, notes, “To deny women is to deprive a country of labor and talent ….[and] to undermine the drive to achievement of boys and men.” These women have asserted their voices.

That dance serves as their means of exploration and expression is not surprising. While each of their works speaks through modalities of modern, post-modern and contemporary dance, the issues they struggle with are age-old. Although some of their methods might seem naïve or old-fashioned (in the 20th-century sense) to jaded American dance goers, promoting democracy and equality for all remains constant

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2012-13 issue of Ballet Review, p. 9. To subscribe to Ballet Review, send a check ($27 for one year, $47 for two years) to: Ballet Review Subscriptions, 37 W. 12th St., #7J, New York, NY 10011.

© 2012 Lisa Traiger

Timeless

Eiko and Koma

September 14 and 15, 2011

Kogod Theatre, Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center

University of Maryland, College Park, Md.

By Lisa Traiger

© 2011 by Lisa Traiger

Eiko and Koma choreograph at the intersection between earth and sky. They dance of earth and air, fire and water, animal and avian, and the elemental lifeforce: birth, death, sex and regeneration. Their dances reflect a vision of the world that is at once timeless and ageless, primal and new agey. The husband and wife duo — artistic partners for nearly four decades — returned to the Clarice Smith PAC for the first of three visits this season as part of a year-long creative residency, which includes both a retrospective of their collaboration on their singular choreographic vision and a new work to be made with contemporary music experimentalists the Kronos Quartet.

Aptly titled “Regeneration,” the duo’s first visit this season looks backward on their career-defining artistic output, beginning with last year’s “Raven,” and moving back in time to one of their earliest efforts, “White Dance,” from 1976. The four-decade span sheds light on the duo’s remarkable ability to captivate attentive dance goers with their distinctive manner of capturing the primal and most elemental nature of humanity and presenting it in living, breathing sculptural, painterly and poetic terms. Their bodies painted a chalky white, recalling the influence of Japanese butoh masters Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, Eiko and Koma become one with whatever and wherever they are performing. At the Smith Center, they swath the black box stage in a white canvas, seared with burn marks and strewn with black feathers and dried grass. They have also adventurously performed outdoors in a customized wagon-like caravan, at the base of an imposing canopy of a large oak tree, in a river and in a church cemetery, among other locales.

“Raven” begins in quietude. Pueblo-influenced composer Robert Mirabal’s drum-centered score, drawn from his original work with the duo on their 1991 piece “Land,” sets the work’s pace, as first Eiko, a thin slip of a woman, stretches and flexes from a fetal position. At one point she uncurls her toes one at a time, like a baby splaying her fingers. Later Koma enters, his movement more erratic and full bodied when played against Eiko’s finely porcelained shapes. The dance, though shortened to 25 minutes for this retrospective evening, feels like an incantatory chant, an appeasement to the gods and nature danced through the wildness of Koma’s stomps and forceful reaches skyward, and Eiko’s more restrained entreaties to a gentler earth mother.

“Night Tide,” a briefer duet from 1984, follows and becomes a paean to the beauty of the body. Danced without clothes, their bodies starkly white, the two become slow moving sculptures, amplifying their joints and muscles, flexed elbows and splayed toes, arched backs and bared buttocks. The sensuality here sings of the body beautiful; aesthetic in its everyday grace, magnified by the languorous pauses and meditative repose they attain in performance.

“White Dance” is the first work the pair performed in the United States and it reflects most vividly their early butoh training. The program’s excerpt of the 1976 work uses baroque music — Bach’s Concerto for Harpsichord No 5 in F Minor and an Agincourt Carol — to oddly unusual effect. There’s Koma prancing around the same white canvas, kimono-clad, a look of pleasant tom-foolery on his face. At one point he hefts out and spills a bag of potatoes. It’s light and comical and recalls that the oft-assumed apocalyptic nature of butoh was just one side of the Japanese, post-Hiroshima dance form. Butoh also has its playful, absurd side and that’s where this dance is rooted. Later Eiko, wrapped in a printed kimono, becomes one with the backdrop, a moving image of silken threads woven into paisleys of butterflies and flowers. She nearly emanates a perfume in the delicate manner that she wafts gently across the scrim of two dimensional multicolored art, her body becoming one with the two dimensions.

There’s a boldness and uncompromising steadfastness knitted into the way Eiko and Koma fearlessly approach their movement projects. They never doubt the integrity of their bodies to speak volumes about life. In slowing down and living in the moment, they teach us lessons of profundity that are sorely needed in a world encumbered by the multitasking demands of technology. At a point in their lives when most dancers have long left the stage for more forgiving pursuits, Eiko and Koma create work that is ageless and timeless.

I heard chatter in the lobby after the show that tap was not an expressive medium to carry forth the heavy message this show imparts. But tap is exactly the appropriate genre to pull back the curtain on America’s long-standing racist and hate-filled roots. With its heavy-hitting footwork by Webb and Edwards, its lighter more nervous tremors from Wilder’s solo performed in prison stripes, to the chorus line of leggy beauties from the Divine Dance Institute, tap is exactly the right means to express the anxiety, fear despair and hope these men represent as they parse through the history of slavery, racism and discrimination in America. REFORM, in ways, reflects and moves past some of the methods and materials in the groundbreaking 1995 musical Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk, of which Wilder is an alum, but REFORM feels more like a sequel, taking audiences further by immersing them in the ramifications of black-men’s actions that are still statistically more likely to land them in jail or dead, than their white counterparts. REFORM is difficult to watch and doesn’t leave audiences with much uplifting. Rather it’s a call to both acknowledgement — particularly for privileged audiences, white or otherwise — and action.

I heard chatter in the lobby after the show that tap was not an expressive medium to carry forth the heavy message this show imparts. But tap is exactly the appropriate genre to pull back the curtain on America’s long-standing racist and hate-filled roots. With its heavy-hitting footwork by Webb and Edwards, its lighter more nervous tremors from Wilder’s solo performed in prison stripes, to the chorus line of leggy beauties from the Divine Dance Institute, tap is exactly the right means to express the anxiety, fear despair and hope these men represent as they parse through the history of slavery, racism and discrimination in America. REFORM, in ways, reflects and moves past some of the methods and materials in the groundbreaking 1995 musical Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk, of which Wilder is an alum, but REFORM feels more like a sequel, taking audiences further by immersing them in the ramifications of black-men’s actions that are still statistically more likely to land them in jail or dead, than their white counterparts. REFORM is difficult to watch and doesn’t leave audiences with much uplifting. Rather it’s a call to both acknowledgement — particularly for privileged audiences, white or otherwise — and action.

It all looks ridiculously simple, but every moment, every movement, each twitch of an eyebrow or tug at a shirt, is planned and telescopes meaningful messages about friendship, gender, heartbreak, and perseverance, not only in the face of failure, but also, even more important, in the face of ordinariness. Happy Hour is about elevating the ordinary to high art. Buying supplies at the local drug store for a performance at The Kennedy Center, taking old steps and making them fresh and new, culling from pop classics but finding new statements or highlighting their meanings in new ways — this begins to get at the depth of Happy Hour.

It all looks ridiculously simple, but every moment, every movement, each twitch of an eyebrow or tug at a shirt, is planned and telescopes meaningful messages about friendship, gender, heartbreak, and perseverance, not only in the face of failure, but also, even more important, in the face of ordinariness. Happy Hour is about elevating the ordinary to high art. Buying supplies at the local drug store for a performance at The Kennedy Center, taking old steps and making them fresh and new, culling from pop classics but finding new statements or highlighting their meanings in new ways — this begins to get at the depth of Happy Hour.

![Eiko-Koma-Land-01[1]](https://dcdancewatcher.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/eiko-koma-land-0111.jpg?w=251)

leave a comment